When David Torres left Denver for vacation last week, he hoped he'd get a break from thinking about his childhood home.

In 2014, not long after his father passed away, representatives from the city approached him and his mother to acquire their Baldwin Court property as the wheels began turning to renovate the National Western Center nearby. It was the start of a long negotiation that ended with Torres and his mother relocating out of the neighborhood.

"It wasn't our choice to leave the house," he said.

Over the last few months, he checked in regularly to see if his family's old home was finally gone. He watched as houses and businesses around the yard were leveled, then his dad's garage and a shed out back. When he headed out of town on vacation, he asked his brother to check in once more for him.

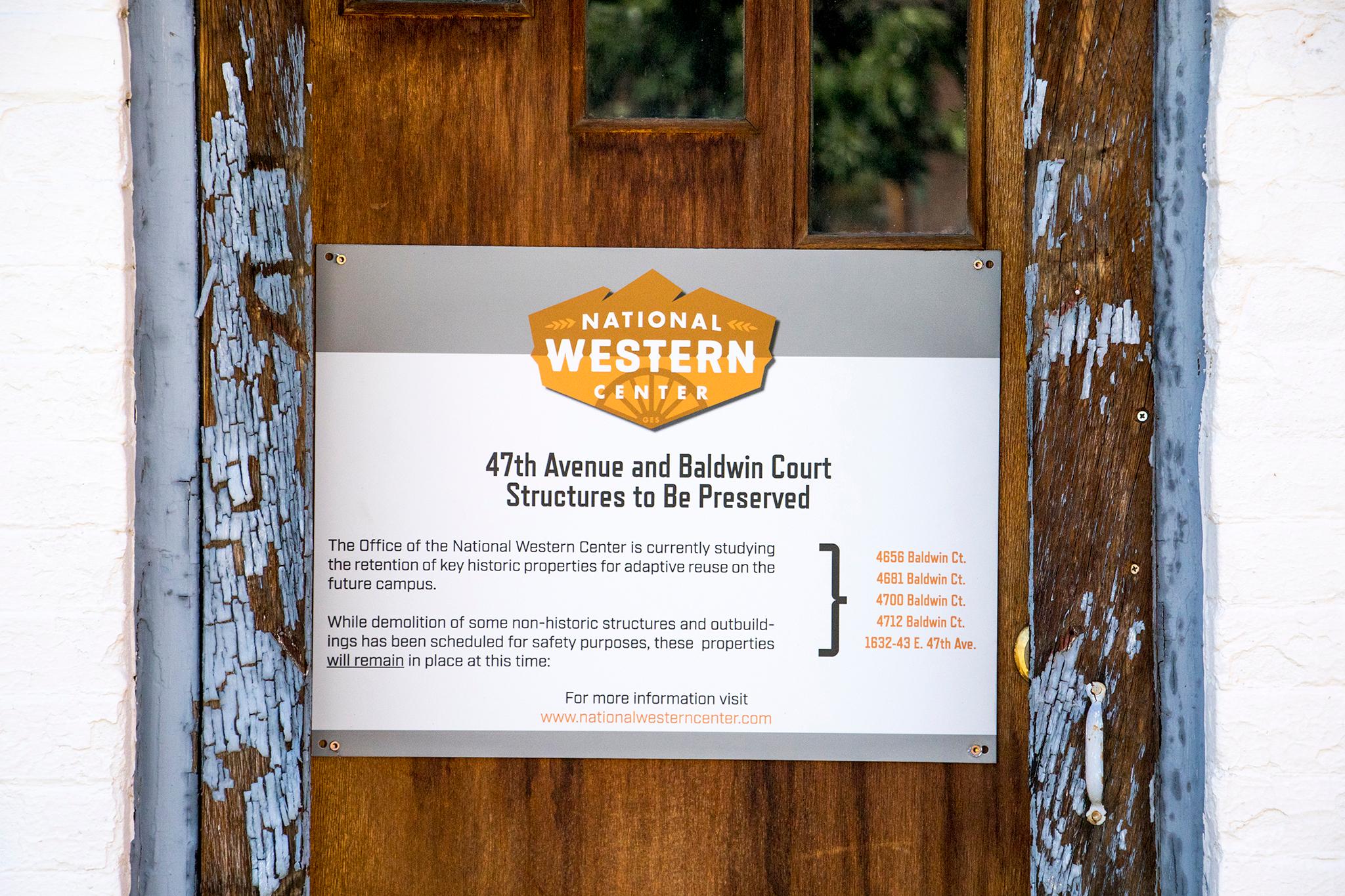

His brother sent back a photo. It was a flyer tacked to a boarded-up window that read: "Structures to be preserved... The Office of the National Western Center is currently studying the retention of key historic properties for adaptive reuse on the future campus."

"And that’s when I was livid," Torres said, thinking back. "I said, 'What do you mean?'"

The possible preservation of Torres' childhood home is one piece in a larger effort to lift up North Denver's history as part of the National Western project. There's no certainty that it will, in fact, remain standing when the project eventually finishes, but it's reopened a wound for a family who feels they were swept aside by the city's ambition.

The National Western Center's future identity revolves around history

Construction on the National Western Center began in November of 2017. The $800 million project is expected to continue construction into the 2020s, and is being touted as a year-round entertainment and trade show venue that "benefits the local neighborhoods, the Denver metropolitan area, the P-12 school system, our interwoven network of higher education and cultural institutions and the state of Colorado."

A key talking point is that the project "also celebrates Colorado’s western heritage."

To that end, Shawn Snow, historic and cultural resources manager on the project, said he's trying to save all manner of artifacts from the historic site.

"It’s a growing list," he said, that so far includes metal troughs, gate hooks and "hundreds of linear feet of wooden pens."

And yes, structures are part of the effort. Snow's team is studying how to save an old sheep bridge from the area's days as a meatpacking hub. They're trying to figure out if they can move the site's historic water tower and what to do with an old railcar. Snow expects the historic Armour & Company Administration Building, which dates to the early 20th century, will be approved for historic Landmark designation.

The goal is "creating a more interesting place that will tie in the history of the site with the new campus," Snow told Denverite, "to integrate some of that past history so we can tell that story for the next 100 years."

Snow said some of the wood and items could be reused in public art or in new buildings' designs.

"The structures are just under study," Snow said of the houses on Baldwin Court, "pulled from our demolition list."

That area has been marked for a future construction phase, known as "The Triangle." A spokesperson from the Mayor's Office of the National Western Center said in an email that part of the project is "underfunded" and likely won't begin work until the first and second phases are closer to completion. While The Triangle doesn't have a projected completion date yet, it's expected that the first two phases won't be finished until 2023.

So the future of Torres' family home is not certain.

In an email, Jenna Espinoza-Garcia, communications director for Mayor’s Office of the National Western Center, said they had to move out one way or another: "While the house may be preserved, it will eventually need to be moved to accommodate the future phases of the site."

Torres said he'd have fought harder to keep the home or hold out for more money if he'd known the words "key historic property" would be slapped onto it. While he managed to get about $499,000 in the deal (about $250,000 for selling the house and $250,000 for the trouble of relocating), he said he still couldn't afford his new home outright.

"I assumed the burden of a mortgage when that house was free and clear," he said. "Anything with 'key historic' in front of it is worth some money."

In her email, Espinoza-Garcia said the properties were not designated ahead of time because "land acquisition does not relate to historic assessments."

She also said that historic designation could result in higher value for a house, but that depends on where it's located.

Ultimately, Torres said, his anger is about something beyond the bottom line. (Oddly, it's not the first time his family has lost property to city projects. The plot where his grandmother once lived and father worked was scraped to make room for an I-70 onramp in 1999.)

"It's something worth fighting for, because it was kicking my mom out of her house," he said. "I don’t want to fight for the money, I’m fighting because it’s wrong."

There's probably nothing he can do about it now.

Denver attorney Doug Widlund, who has worked on all kinds of land acquisition cases, said it's common for properties to take on new uses after they've been bought outright or through eminent domain cases.

"The rule is, if the taking was kosher at the time," he said, "whoever the taker is really free to do whatever they want with it."

He pointed to one example in particular. In 2007, a couple tried unsuccessfully to win further compensation from the City of Aurora when their former property, acquired through eminent domain, shifted from being used for a highway and was instead used for a shopping center.

Torres is not looking forward to catching glimpses of his childhood home as he drives over I-70 or to his job at the Purina Pet Food plant. He called it a "tombstone."

UPDATE: This story originally quoted Espinoza-Garcia as saying, "Historic designation of a home or structure does not usually increase the value of a property. Often times, a historic designation decreases the value of a home given the restrictions applied to the property by this designation." She called Denverite to say that this information was not correct. Historic designation often results in higher property value, though it depends heavily on where a home is located.