Helen Alvillar's son Leo Espinosa died of a drug overdose on May 6, 2008. He was her only son.

"At that time, I wasn't aware of how many loved ones we were losing to overdoses," Alvillar said on Monday while speaking at a Denver City Council meeting. "We need to raise our voices to make everyone aware of this epidemic.

Before speaking, the council unanimously approved a proclamation recognizing International Overdose Awareness Day, which takes place Friday. In Denver, it means recognizing the 201 fatal drug overdoses in Denver last year, a record for the city.

Across the street from the Colorado Capitol, community members who died from overdoses are already being memorialized.

Their names and photographs are attached to a memorial wall inside the Harm Reduction Action Center, which provides services for users including a syringe exchange program. Alvillar serves on the center's board of directors.

“Because we have so many folks on our wall, we had to recently reorganize, because we couldn’t bear starting to add photos to another wall,” Harm Reduction Action Center executive director Lisa Raville said Monday. “All of these folks were loved. And I know that because I loved them, too.”

Opioid drug overdoses are now killing more Americans than car crashes and gun deaths, with preliminary nationwide 2017 figures showing more than 70,000 people have died from overdoses.

“Whereas, overdose is now the leading cause of deaths —,” Councilman Albus Brooks said, pausing while reading the proclamation, “I need folks to realize this: It is the leading cause of death of Americans under the age of 50.”

Raville said locally, most of these could have been prevented. She wore the names of the people who have died from overdoses on her chest and sleeves.

“Most of these names on me today represent the ages of 17 to 40,” Raville told the council. “Many of these folks passed away in residences, in hospitals, parks, cars, stairwells, underneath bridges, underneath viaducts, bathrooms, shelters, motels and hotels, to name a few.”

On Friday, communities across the world will collectively mourn people who died from overdoses.

According to its website, International Overdose Awareness Day started in 2001 in Melbourne.

Locally, HRAC will host a public event on Friday from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. at its offices at 231 E. Colfax Ave. Raville is asking community members and media to arrive at 1 p.m.

“This is a day where we mourn those we have lost and fight like hell alongside those with us,” Raville said on Monday.

Brooks said the day helps publicly challenge the stigma around drug use.

Like others in attendance, Brooks said he had a personal connection to opioid use: He said became "reliant" on them after they were prescribed to as part of his cancer treatment. It made him realize how easy it was to become dependent and how people can be susceptible to the potential for addiction.

“Overdose Awareness Day sends a strong message to the current and former drug users that their lives are valued,” Brooks said.

The Harm Reduction Action Center is still pushing for a supervised injection site as part of its services.

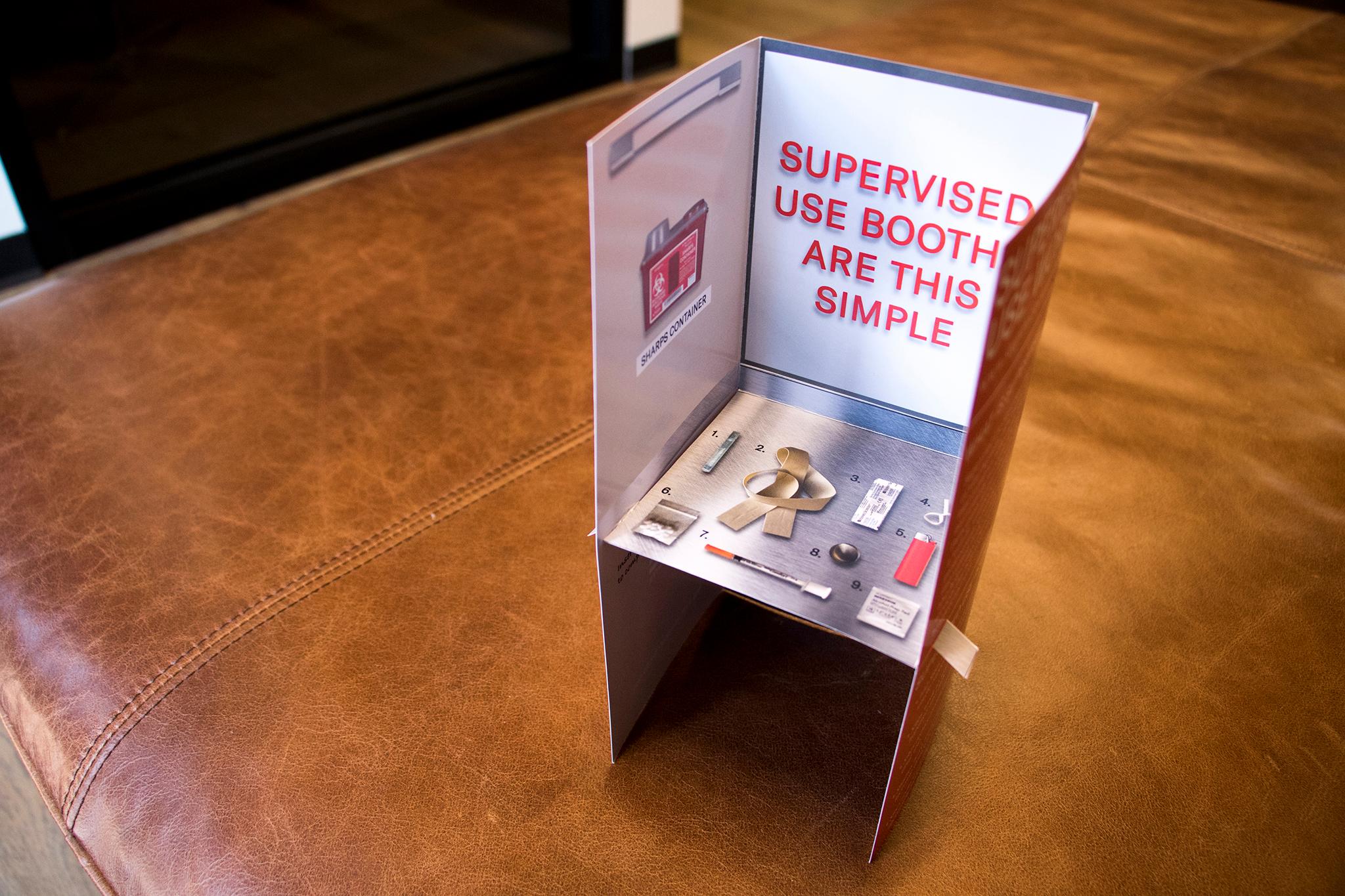

In the corner of a back room at HRAC is a mock-up supervised injection booth.

The center has even created brochures that can be folded to create a tiny version of the site. The brochure lists benefits as well as the materials that would be provided.

During an interview earlier this month, Raville talked about why more people should support the controversial measure as she sat near the mock-up.

It's currently illegal to have a safe injection site. Raville said it would amount to use and possession on a property, prompting a potential property seizure. She's hopeful that legislation legalizing the sites at the local level will be introduced next year.

"I would need to exempt use and possession on a property in the city ordinance and then a statewide law to be able to operate that," Raville said. "It would still be out of federal compliance, but so are a lot of things, like marijuana, immigration stuff."

The drugs would be obtained off-site; users would inject themselves.

"I'm just simply trying to take it out of businesses' bathrooms," Raville said. She said she currently has the backing of about 50 businesses and organizations who support the idea.

"We're interested in a pilot situation," Raville said. "There's a ton of data and research from years and years and years of the supervised consumption sites, so then we would make sure in parallel, to do that."

Brooks said on Monday the city should consider safe consumption sites as part of their overall framework. The city's strategic plan, which was released by Mayor Michael Hancock's office and the city’s public health department last month, includes suggestions for creating "safe places for people to use substances" as a way to reduce harm.

"I think the City of Denver is a perfect place for us to pilot these new ideas," Brooks said.