A couple of weeks ago, developers met with Capitol Hill United Neighbors (CHUN) historic preservation committee to discuss plans for a pair of old houses that have been lurking vacant behind the vape shop and the old Bourbon Chicken headquarters on East Colfax Avenue. Even though the homes have long sat empty and in disrepair, they're part of the Wyman Historic District, a Landmark preservation area; any project that might alter the structures needs special approval, and this meeting was developers' first outreach to see what might be viable.

Architect Chris Shears, who's working with development partners Lance Gutsch and Kiely Wilson to find new use for the block, prefaced the conversation before unveiling their ideas: he is a longtime preservationist in Denver. He's worked on a number of projects to save old buildings across the Front Range, like the Flour Mill apartments and the Dairy Block downtown. He and the development team care deeply about saving the past – but in this case, preservation might not be economically realistic.

Shears then unveiled a rendering of what could, one day, sit on the block: an eight-story, mixed use apartment building.

The CHUN preservationists in the room balked.

"When you gloss over the details, there's a moment when buildings are lost. I think we just had that moment in this meeting," said David Wise, an architect who works out of an office just a couple of blocks from the Franklin Street lot. "Was the historic designation meaningless? That’s the question that keeps us up at night."

There are always details to work out and neighbors to appease with a new development. But when it comes to a new project on a historic block, things can become a little trickier. In this case, developers and preservationists each came to the table ready to fight for their own interests. At first, the conversation might seem like a skirmish, but both sides agree that their negotiations are likely the only way to produce a product that's better in the end than anyone's initial idea.

Developers said the money needs to work to save old property

"We wouldn’t be here if we thought there was any way to preserve these buildings," Shears told the meeting. "We’re asking for your help."

Wise fired back: "It’s entirely savable."

Was it technical or financial challenges motivating their desire to scrape the block, he asked?

"Both," Shears replied.

Speaking separately with Denverite, Shears said projects to rework old buildings usually have hidden costs that often aren't realized until work begins. They could find, for instance, that entire structures beneath floorboards are totally rotten. On top of that, it's usually a massive burden to update old structures to current code. In most cases, any new structure that might be built on a historic site needs to subsidize the cost for rehabbing old buildings.

And development in Denver can be difficult even without dealing with a Landmarked structure.

"It's riskier," Shears said. Construction and land costs are high in our hot market, which leaves less room to deal with a potentially rotting building.

With the Franklin project, there's also an issue of the added commercial space along Colfax. Wilson, who co-owns the property, said those structural changes means they wouldn't just be saving the near-century-old homes, but also the newer additions. It's not exactly what one might imagine when it comes to preservation.

"They've been so altered they've lost their integrity," Shears said.

Wilson said this is his group's first landmark acquisition, and they knew it would be an especially rigorous process when they bought it. But the area, right where Park Avenue meets Colfax, was alluring enough to go for it. He added the process so far hasn't deterred him from looking at similar sites in the future.

"We loved the location, we loved the neighborhood and we figured we’d be able to figure out a project," he said.

Initially, they imagined they could incorporate the old structures, but they changed tact after learning a little more about the site.

Despite their unpopular first proposal, Wilson and Shears said they heard the neighbors loud and clear. They're taking time to revisit their plans before they bring any new ideas to the table.

But that extra deliberation, too, means more risk on their investment. Paying property taxes and insurance, not to mention commissioning new designs, Wilson said, "It can eat into your margin pretty quick."

But he emphasized the extra time and expense is worth it.

"If it takes a little bit longer on the front end to make sure the neighborhood is happy," he said, "we are all about that."

Preservationists fear they could lose valuable history and, critically, set a precedent for more demolition down the line

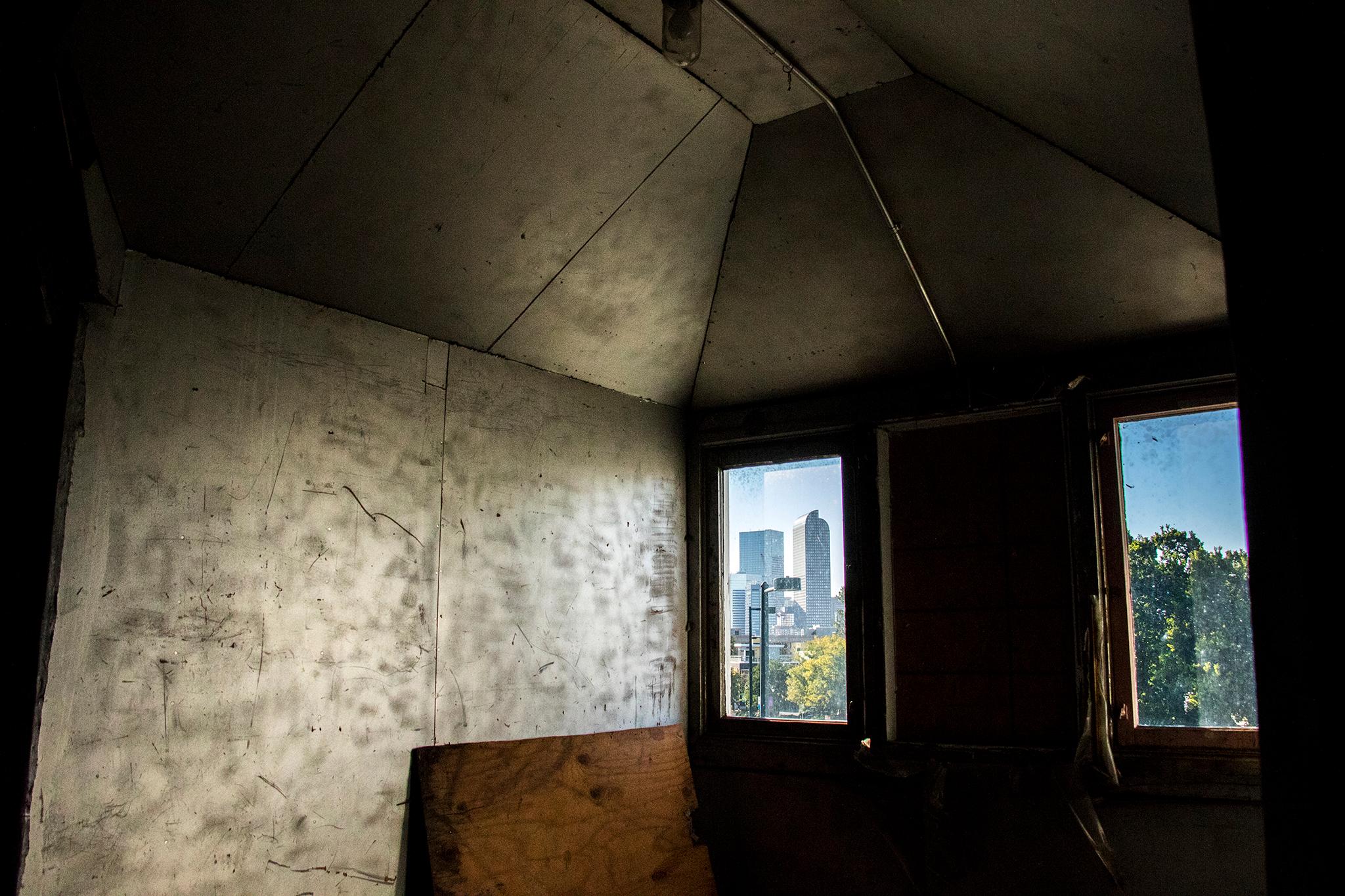

At the end of the CHUN meeting, Shears, Wilson and Gutsch offered to take the preservationists on a tour of the old buildings so they could see for themselves how bad the structures really are. So, a few weeks later, they met the community group on Colfax and brought them inside. The result was maybe not what they had hoped.

As the group entered into the first building, an old home that was later used as a fur shop, the preservationists "ooh-ed" and "ahh-ed" at the old floors, an opulent spiral staircase and chandeliers hanging from a stained-glass skylight above.

Wise later told Denverite that the visit might have strengthened resolves.

Generally, the CHUN group has doggedly advocated to save structures all around Capitol Hill. The group filed for Landmark designation on the old Cathedral High School property a few years ago, when a developer interested in scraping it came along. That foiled the builder's plans, and allowed the preservationists to hold out for another group with better plans. The old high school is now set for a full renovation, and it will be incorporated into a boutique hotel that will break ground in coming months.

Wise said the tour was a flashback to another fight, when interests at the Capitol were demolishing old buildings for additional parking. One property in question was a mansion at 10th Avenue and Grant Street. He helped organize a brainstorming workshop inside the mansion where architects gathered to sketch up ideas for how the building could be saved. That meeting galvanized support behind a preservation effort that was eventually successful.

CHUN's efforts to save the buildings at Franklin and Colfax aren't just about saving those two structures. For some, it's a battle to make sure Denver's historic preservation systems stay relevant for future challenges.

If they let this go, Wise fears, "it would weaken immediately all efforts of historic preservation in Denver."

"Setting a precedent for scraping in historic districts is a real concern," Annie Levinsky, Executive Director of Historic Denver, Inc., told Denverite in an email. "The foundation of the landmark program is to protect buildings long into the future, and there needs to be some certainty and consistency about that intent. If these homes go down, what is next?"

She added that these particular homes are some of the last of their kind along Colfax. The fact that they've been modified to accommodate businesses actually makes them more valuable, she said, since they mark a point in time when the wicked drag transitioned from a residential to a commercial thoroughfare.

And the developers' concerns that preservation might be economically infeasible is something she's used to hearing.

"If you go back to the beginning of the modern preservation movement in the 1960s, you’ll hear this refrain regularly," she said. "People said it about Larimer Square, they said it about Union Station, they said it about almost every warehouse in LoDo in the 1980s, but those with vision persisted and have seen the economic upside."

Wise also made the point that developers probably knew what they were getting into, and allowing them to scrape the lots would be a "windfall," since they would be getting out of the preservation costs that otherwise were assumed to be part of the purchase.

"If anything less than the preservation of these buildings occurs," he said, "the developer is getting an advantage through a policy change."

While the Franklin Street debate is far from over, all parties involved are confident the process will yield something better

At this point in the process, the CHUN preservationists will continue to fight for a palatable solution.

"Our committee should do its duty now. It's all we can do," Wise said. "We need to stay clear about our mission our duties our values and speak up."

But he's known Shears for some time, and he's confident the developers will be able to figure something out.

"He is capable of making this whole thing work, which is not true of all development teams," he said.

Generally, Wise said he was grateful that everyone involved was earnest and approachable. There are some real "bullies" in this field, and that's not what these guys are.

And beyond his faith in the developer's aptitude, he added that this process is normal and necessary to produce a great product: "These discussions, in my experience, typically lead to new and better ideas."

While Wilson is not ready to say what his team might unveil next, he also expects their tug-of-war will result in an improved plan.

"I think really there’s an outreach process," he said. "The reason we do that is so we have a better project at the end of the day."