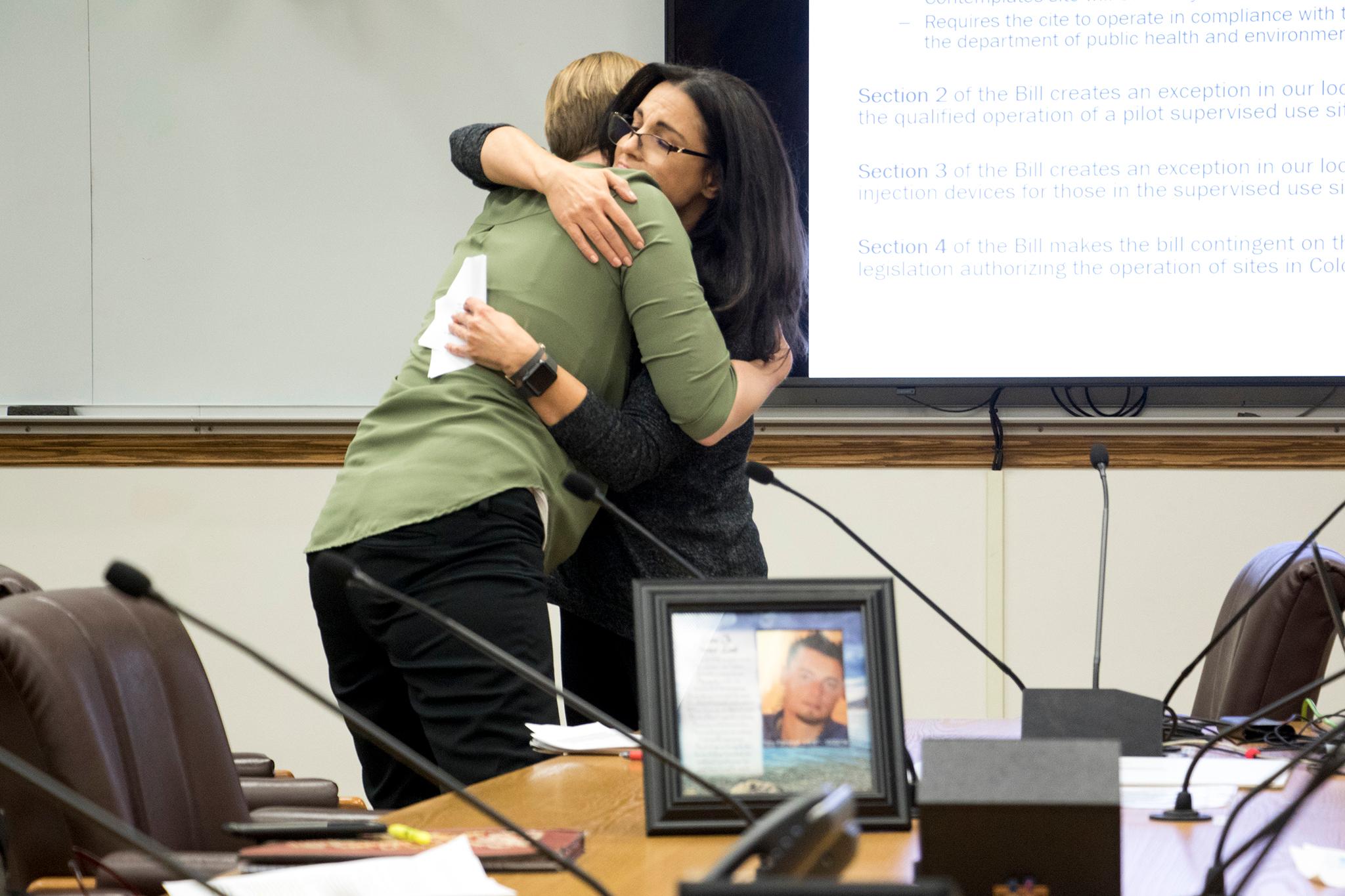

Hundreds of people probably walked, ran and biked by Tony Fairchild as he accidentally overdosed on the Cherry Creek Trail and died four years ago, says Joelle Fairchild, his mother. The 27-year-old had injected heroin.

"It's an ongoing battle to balance the pain and guilt of outliving your child with the desire to live in a way that honors them and their time on this earth," Fairchild said. "A supervised use site could've saved his life."

Fairchild was one of 15 people signed up to testify at a Denver City Council committee Wednesday in favor of a "safe use" site where people addicted to opioids and other drugs can take them safely with sterile kits and staff on hand to prevent overdosing. The sites would also act as gateway to longer term treatment.

The Safety, Housing, Education and Homelessness Committee unanimously advanced the ordinance, proposed by City Councilman Albus Brooks, to a full vote. The law would open a site in Denver on a two-year pilot basis if the Colorado legislature legalizes it in 2019 -- which is more probable today than it was Tuesday, Brooks said, now that Democrats control both chambers of the legislature and the governor's seat. A similar measure failed last year.

But it's not about politics. It's about saving people's lives, supporters say. More than 200 people died of overdoses in Denver last year -- the most on record -- and more than 1,000 people OD'd statewide. No one has died at a safe drug use site since they first started popping up 30 years ago, according to data provided by the Harm Reduction Action Center.

"We're not pushing this," Brooks said. "We're responding to a community and a public health crisis."

The policy is in response to an epidemic of heroin, fentanyl, methamphetamine and other drugs that killed 64,000 across the country in 2016. No safe use sites exist in America. Denver, along with Philadelphia and New York, will lead the way if the full city council and the state legislature approve the pilot.

Doctors, social workers, public health experts, and current and former addicts support the law as a scientific and moral imperative.

"Physicians feel very strongly about the opioid epidemic," said Donald Stader, an emergency room doctor at Swedish Medical Center. "When you look at the science, it is indisputable that this will save lives ... that this will improve health in our community."

Kelly Reed's friend died a week ago after overdosing. The victim was surrounded by people with a OD preventative drug called Naloxone, she said, but did not use it for fear of being searched or arrested when police showed up. Reed said she would have used a safe use site, if available, when she was a drug addict. And that "every person that would inject their substance of choice will be doing it and continue to do it with or without these sites."

"We understand the risks involved in injecting," Reed said. "The substance has us so wrapped around that the risk is certainly worth it to us in those moments. Having said that, when faced with the simple fact of injecting myself by myself, secluded with no one to find me, versus a site to have someone there to make sure I don't die, the choice is easy."

Denver doesn't have enough drug treatment centers.

The Harm Reduction Action Center sees between 120 and 150 people every morning, and users often have to wait days to get treatment beyond the Band-Aid the organization provides, like needle exchanges and testing for fentanyl laced heroin. Denver Health has limited space for people suffering from drug addiction, and sometimes turns people away, according to Raville.

So the question is where people go after using safely to get long-term help. The answer, for some, will be nowhere. They may repeat the cycle of using to avoid withdrawal, but better in the presence of people who can save their lives than in a bathroom somewhere, Raville said.

A measure known as "Caring for Denver" passed Tuesday to fund mental health. That gives Brooks confidence despite the lack of services.

"While that's an issue, there's a lot of hope that I'm being given from Caring for Denver, and an ordinance like this pushing the system and putting a light on the system that we do have huge issues -- Medicaid, lack of ID, things like that -- for treatment," he said.

The ordinance could free up political will to fund more treatment centers down the road, Brooks said.

Art Way, director of the Colorado Drug Policy Alliance, felt similarly.

"This is a reality based, compassionate, human endeavor," Way said. "When it comes to the issue of drug dependency, we try to hide that issue, push it into the corners, push it into the shadows. And if you support safe use sites, you're bringing the issue to the table the issue to be addressed. And no longer is it an issue of back alleys, no longer is it an issue of restrooms at the library or at the local Wendy's or 7-Eleven."

Mayor Michael Hancock supports the proposal.

He'll have to sign it into law should the city council pass it.

The Hancock administration released its Opioid Response Strategic Plan earlier this year, which aims to “reduce barriers to safe use sites” and “implement innovative service facilities that are open and welcoming to people who use drugs.”

“Like cities across the country, Denver is seeing significant numbers of people dying each year of drug overdoses," his office said in a statement. "The mayor applauds Councilman Brooks for looking for innovative answers. While we do have significant legal concerns, and there are many implementation details to work out, the mayor supports this proposal.”

The safe use ordinance heads to the full council for a vote November 26.