Two weeks ago, drawn in part by the promise of slinky races for Black Sheep Friday, I finally went and saw Tara Donovan's "Fieldwork" at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

It was beautiful, alien, frighteningly obsessive and maddeningly untouchable.

(This is the part where I remind you that it's really not OK to touch art. The rules of consent apply here as they apply to human bodies: "My body/art, my rules.")

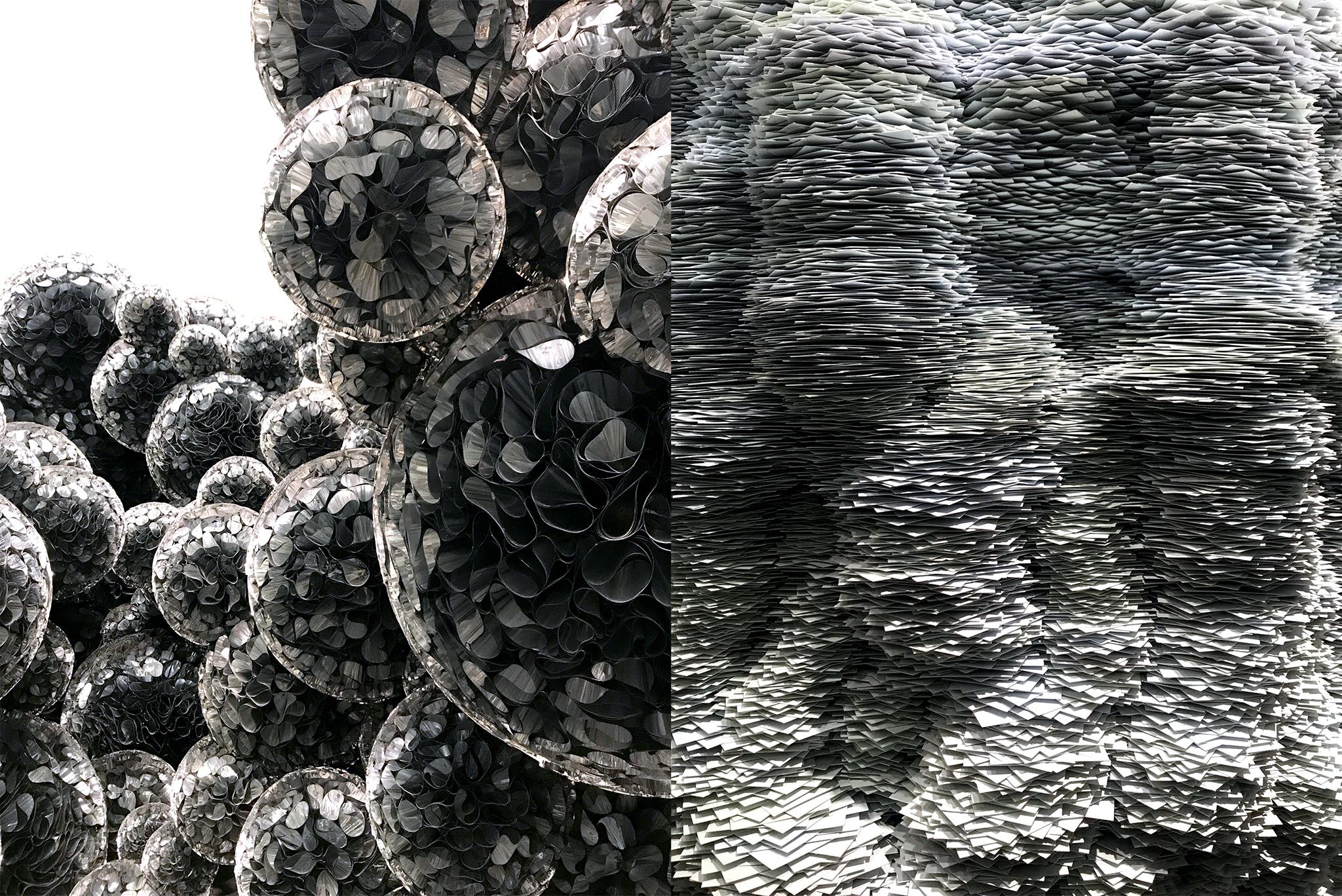

"Fieldwork" -- which opened Sept. 22 and runs through Jan. 27 -- occupies the entirety of MCA Denver's building and just about every single piece of it screams out to be touched. (But, again, do not touch.) Carefully arranged stacks of straws beg to be pressed upon. Piles of paper demand you drag your fingers across their uneven edges. Orbs of shiny paper cones invite you to give a little squeeze.

Twenty or so blocks southwest, the Denver Art Museum is putting on its own spectacular and tactile-ly tempting display. "Dior: From Paris to the World" is the first major exhibition of the House of Dior -- a big get for the DAM and a big old tease for the type of people who touch everything in the store when they go shopping. It features more than 200 haute couture dresses asking to be caressed, scrunched and ruffled. In the case of the Maria Grazia Chiuri creation "Ange Rouge," a red ball gown with tiered tulle fans, you might -- if you are me -- feel an animal urge to press your entire face into it.

So what we have right now are two massive exhibits in Denver's biggest art museums overflowing with things you probably really want to touch but can't.

That got me wondering: What do museums do about this?

"What we do is we hire a lot more gallery attendants and we train them and we re-train them and we check in constantly so they feel emboldened and empowered to say something," MCA Denver curator Nora Abrams said.

Curators coach the attendants on their language so they feel confident in their approach and so guests don't feel embarrassed, just watched, Abrams said.

It's not the first time, of course, that the MCA has dealt with this. Abrams remembers a Marylin Minter exhibit having the same effect on people because the paintings were so vivid and lifelike. The museum welcomed the impulse with that exhibit, as well as with "Fieldwork." They just ask that you don't act on it, and they know prevention is somewhat on them.

"We were inviting people to be mesmerized by these works and by the kind of magic of them, but we had to be responsible in that as well, which is to say, 'Yes, be wowed. Yes, find those moments of wonder,'" she said, but don't touch.

At the DAM, they have a whole department dedicated to satisfying your forbidden tactile desires. The Learning & Engagement Department, communications coordinator Jena Pruett told me in an email, "focuses on the visitor experience in a multi-sensory way, not just sight."

"When Jeffrey Gibson: Like a Hammer was at the DAM several months ago, we had a tactile (touchable) table out in front of the exhibition before people entered, so that they could touch and feel the materials that the artist used, without touching the actual artworks inside the exhibition," Pruett said. "In Rembrandt: Painter as Printmaker, currently on view, we incorporated touch and smell into the exhibition to provide a more intellectually and physically accessible experience for a wider range of visitors."

So the department actually does more than try to placate your childlike urges, which is cool.

Pruett was gone for the holiday before I could ask about any security or insurance considerations for highly touchable art, but you can read more about the DAM's "tactile table" here.

The MCA Denver used to have a room called the Open Shelf Library -- now home to the Octopus Initiative -- where artists could share the materials they used to make their work or that inspired their work. It never realized its full potential, Abrams said, because people are so well trained not to touch anything.

"And I think for the Denver Art Museum, which is so much bigger and has so much art from different time periods and different regions, I think that they have a certain responsibility to demonstrate how materials are used and manipulated. ... For us it's an aspect of the work but it's not the sole aspect of the work," Abrams said. "To over-emphasize the materials kind of takes away from them."