Gertie Grant's brother ran a tree nursery back in the '80s when he found himself with a couple of specimens that he couldn't sell. This did not sit well with Grant.

"I said, 'Charlie, you can't throw trees away. If I get a neighbor with a truck,'" she recalled asking, "'can we take those trees?'"

So she loaded them into a garage and started asking around to see if anyone wanted to make an adoption.

"People were very excited," she remembered, and soon every last one found its way into a local yard.

Neighborhood groups around the city began to take notice, and the program grew into a regular event.

She became, "a grassroots, pardon my pun, organizer," she said. Denver's canopy flourished.

That was the beginning of a program that is known today as Denver Digs Trees, which is now run by the nonprofit The Park People. Every year, The Park People negotiates deals with wholesale nurseries to acquire more than 1,000 trees for distribution. With the help of grant money, they're able to sell trees to Denverites at subsidized cost that can be planted in the public right of way and, more recently, in private yards. A new sapling for your yard will run you about $35, depending on what you select. Street trees are free.

The deadline to apply for 2019's sale is February 15, and representatives from The Park People are telling folks to act fast, since some species sell out quickly. There are at least ten species available this year, although Park People Executive Director Kim Yuan-Farrell said this week that two species might be close to sold out, if they're not already.

In the spring, after applications are in, residents will be notified where to pick up their trees. Most people are on their own to plant and care for their new leafy buddies, although The Park People does provide help for those who need a hand.

Denver has long relied on residents' support to maintain a green city.

In the late '80s, Denver passed a bond measure that put a significant sum toward tree development across the city. But Mayor Federico Peña's administration had a problem: They didn't have the manpower to execute their plan. So they turned to The Park People to see if their existing program could handle implementation. That meant they needed someone to run things full time.

Grant was the obvious choice. When she got the chance, she stepped down as a prosecutor with the Denver district attorney's office and took the position.

"I said I would really like to do that," she recalled. "I would really much rather do this than practice law."

In no time, Grant and Denver Digs were distributing as many as 3,000 trees every year, driven by a "crazy passion" for the project.

Grant said her gusto grew from years growing up along the 7th Avenue Parkway, where she remembers spending her summers in the trees lining her street and in Cheesman Park.

Many of those plantings, Denver City Forester Rob Davis told Denverite, date back to Mayor Robert Speer's tenure in the early 1900s when the emphasis in city planning was all about beautification.

"It's easier to love a place that's beautiful," he said. "Denver back in the 1900s was not a place that would be considered beautiful."

In those early years, the city was pretty treeless, and Denverites were excited to beautify their neighborhoods. They would pull up in horse-drawn carriages to pick up their new saplings. And then, like the program today, they were responsible for planting and maintenance.

"We wouldn't have any of our urban canopy if it wasn't for residents who take care of them," Davis said. It's just too big an effort for the city to handle alone.

Davis said there's no specific regimen for keeping new trees watered, although The Park People has posted some guidelines on their website. Recipients can more or less stick their hands in the soil and see if the roots are dry or not: "If it feels like soup, don't water it, even if it's been three weeks."

And though maintenance is fairly simple, Yuan-Farrell said The Park People spends a lot of time after applications come in making sure new trees will fit appropriately into peoples' yards. It's kind of like getting approved to adopt a new pet.

"We really want people to be planting wisely," she said. Poorly placed trees can become a liability, and the nonprofit wants to make sure their investments grow steadily over the years into a canopy that's large, sturdy and shady.

So, the process might be more complicated than people expect. Luckily, most folks seem to be pretty jazzed about taking on the task. Davis recalled seeing a huge line of people waiting at a distribution site in 2016 despite terribly cold and wet weather.

"You kind of get this special feeling," he said, thinking back. "All these people are standing here in the freeing snow, rain mix just to get this tree to plant in their yard, just to make this city nicer."

Davis emphasized this is about more than visual beauty. Trees' presence in the urban landscape impacts soil and water quality and helps mitigate the "urban heat island effect" that occurs when our built environment absorbs sunshine more efficiently than surrounding natural areas.

A city report from 2013 estimated that Denver's tress remove as much as 290 pounds of pollution from the air each year, and more than 1,000 pounds from the metro area at large.

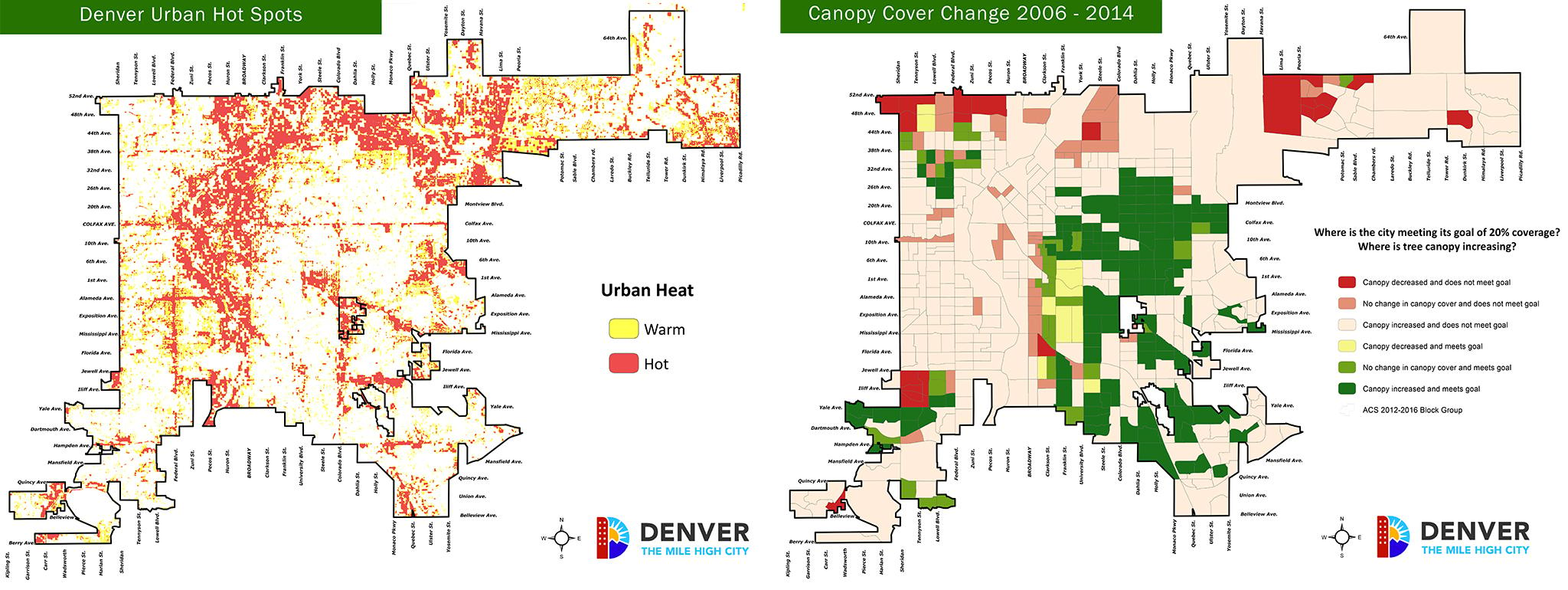

Another set of studies show heat island hotspots in the city as compared to tree canopy growth. These patterns are inversions of each other: where there are trees, there is less heat absorption.

The impact patterns also follow an "inverted L" pattern that reporter David Sachs recently highlighted as a major theme in the city's distribution of wealth and health. Many neighborhoods to the north and west show fewer trees and more heat island hotspots.

The Park People are aware that tree distribution is not equal in all parts of the city, so they've identified 28 "target neighborhoods" that qualify for even lower prices. Residents in these areas can get a specimen for as little as $10, and folks who write The Park People to say they can't afford even that lower price can qualify for a free tree.

To Gertie Grant, all this work sums to a better Denver for everyone. It's about the air and water, it's about a prettier city and it's about bringing people together.

"It's a question of how do we keep our cities livable," she said. The trees: "they have so many valuable effects on how we live in our city and how we treat each other."

This story has been updated.