Like e-scooters, when cars came onto the scene, a lot of people hated them.

The streets were slower-paced social places where kids played and adults bantered. That changed when cars began killing people. Now that cars own the roads, e-scooters are a shock to the system, and Denver is figuring out how to make them work.

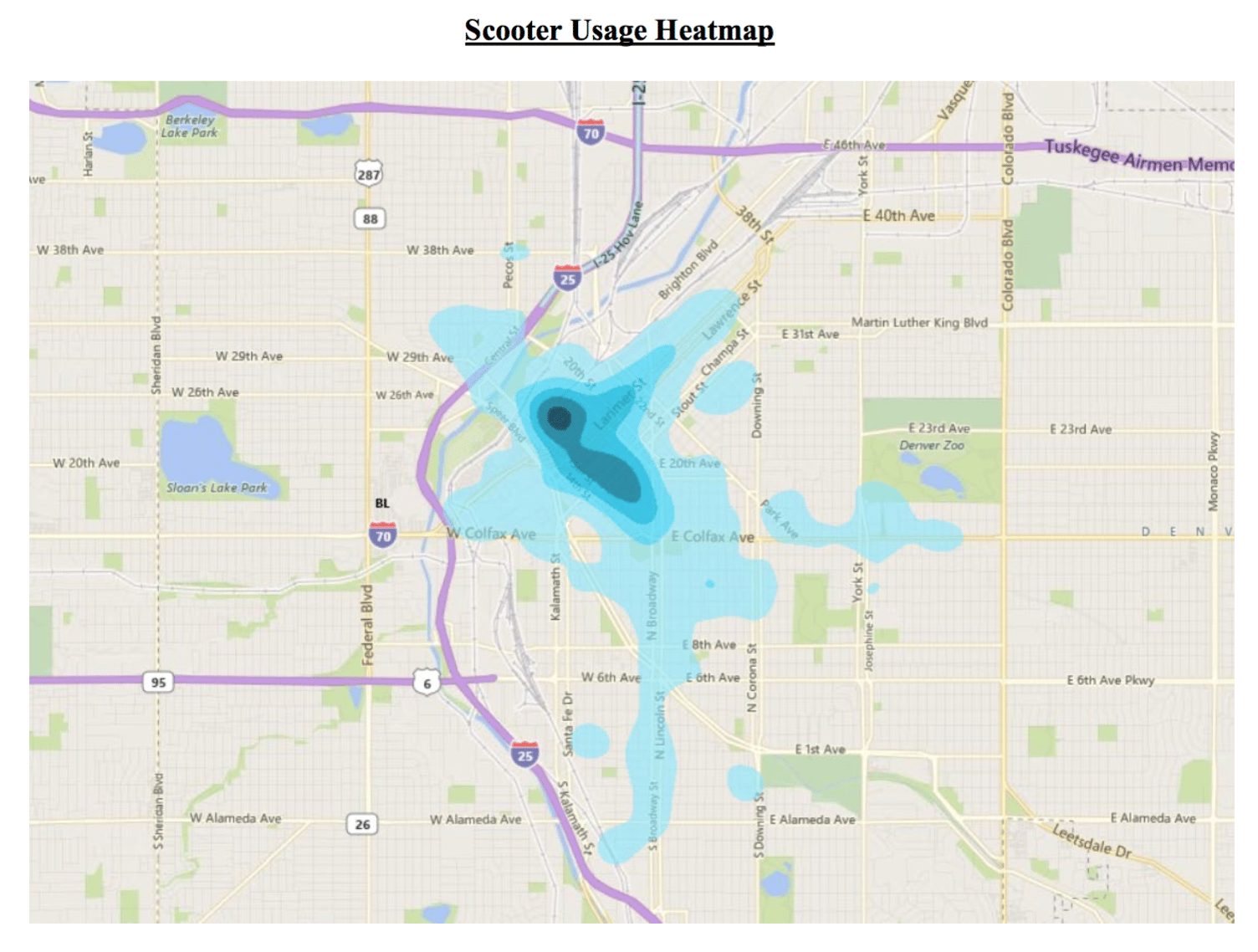

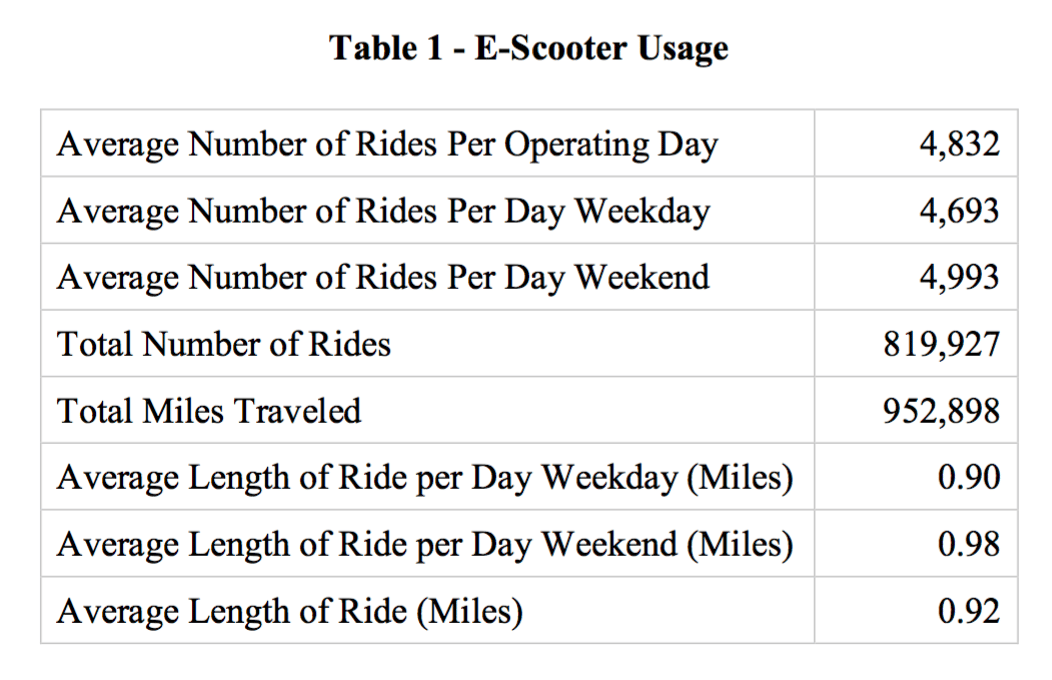

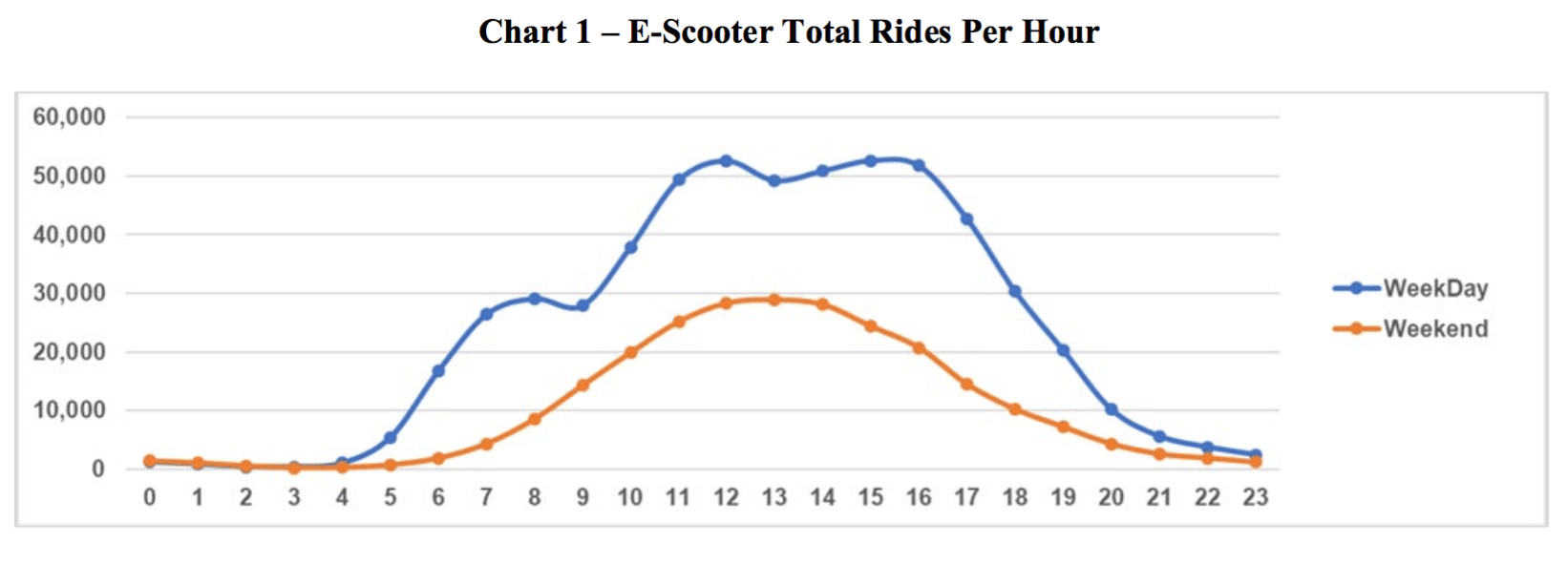

A big piece of the puzzle comes from data provided by the scooter-share companies. Denver Public Works released those goods earlier this month, along with the initial results of a survey of more than 2,000 people. We are now clued in to the behaviors of the much-maligned scooter rider.

According to the (unscientific) survey, 42 percent of respondents either "don't like" or "hate" scooters and 55 percent "love" or "like" them.

Surprise -- if you haven't ridden a scooter, you're less likely to have warm feelings toward them, said Cindy Patton, an advisor in DPW's policy office. If you do scoot, you're more likely to root for the scoot.

People are opting to scoot instead of walking, triggering jokes about a "Wall-E" future.

By next year, Denver is aiming for 15 percent of city trips to be by foot and by bike. That won't happen. The combined "mode share" for those options was about 7 percent in 2017.

Scooters may not help those stats. Of the people surveyed, 43 percent opted to scoot instead of walk. Denver's foremost walking expert, Jill Locantore of WalkDenver, is conflicted.

"I don't know if I know how to feel about it," Locantore said.

On the one hand, walking is so important because of its health benefits, she said. On the other, scooters get cars off the road to an extent, which is good for pedestrians -- 32 percent of respondents said they would've taken a car if not for the scooter.

E-scooters also hog less space and pollute less than cars. Locantore said scooters aren't the problem. The lack of walking infrastructure and amenities, like safe crosswalks, sidewalks and shade trees are.

"My inclination would not be to focus on scooters and crack down but instead focus on all the things we need to do to make walking not just possible but delightful," Locantore said.

DPW's Patton said she and her staff have joked about the movie "Wall-E" coming to life on Denver's streets -- everyone with their little personal transport pods decidedly not moving their legs. (Not unlike, you know, driving cars.)

Patton says it's too early to draw finite conclusions, though. We don't know, for example, if people are always replacing their walking trips with scooters or just using them in a pinch.

"I think it's a matter of what's the tipping point for an unhealthy lifestyle," Patton said. "I don't think that, based on the price point and the limitations to how far they can reasonably go with battery life, I don't see them replacing everything."

Commuters are scooting to work but aren't mingling much with buses and trains.

That's according to ridership data from the scooter companies, which show rides spiking during the morning commute, at lunchtime and during the afternoon rush hour.

Though DPW and scooter companies pitch scooters as the coveted "first-and-last-mile connection" during transit trips, only 9 percent of riders said they scoot often in conjunction with buses and trains.

Denver's scooter experiment technically ends in June, at which point the streets department will decide whether to create a permanent "dockless mobility" program or not. No one statistic will dictate the scooters' future, according to Nicholas Williams, deputy chief of staff for the streets department.

"We don't anticipate a silver bullet point of data that will affect that," Williams said.