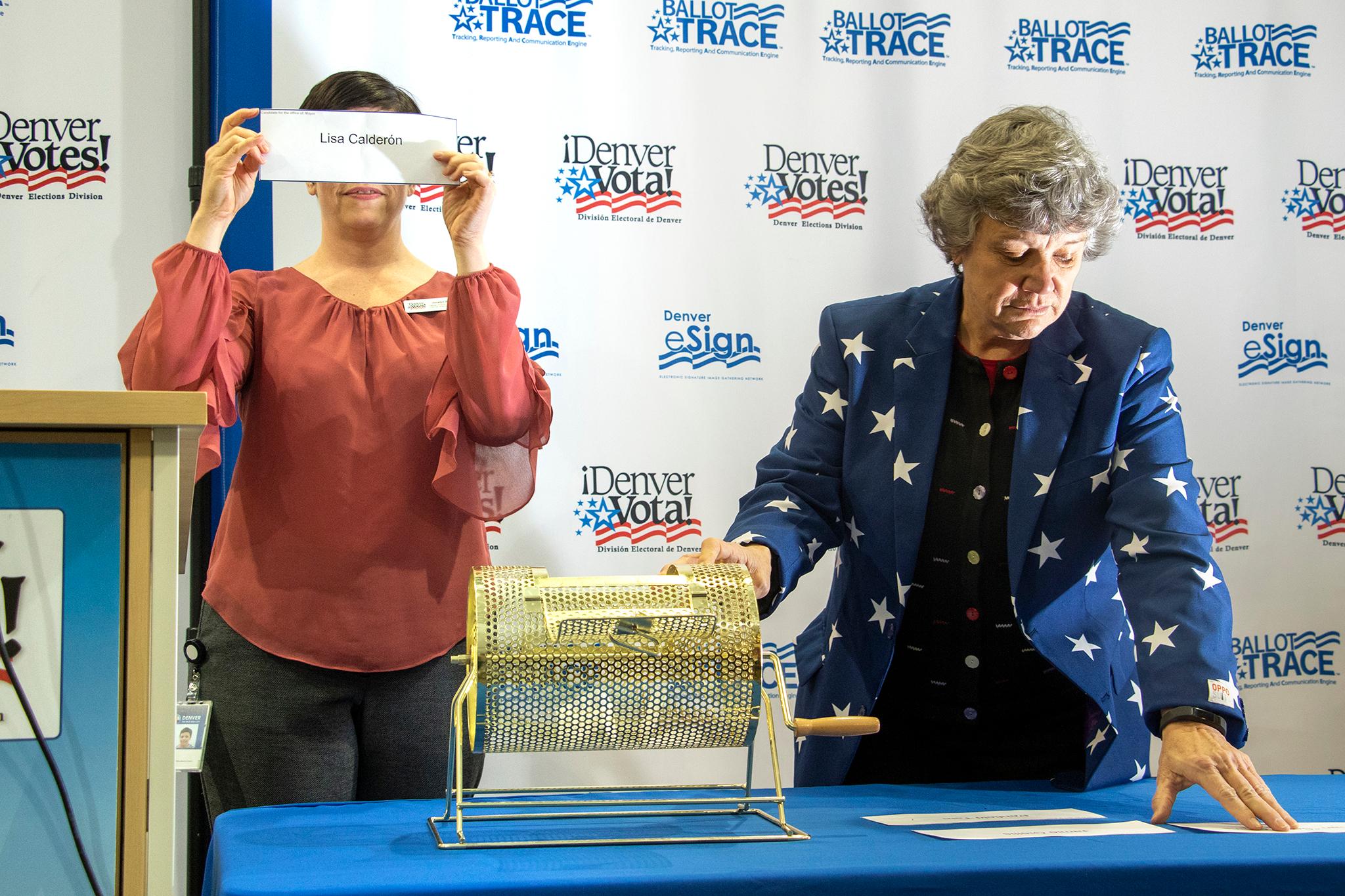

A bunch of candidates for Denver's elected posts gathered at the Denver Elections Division office Thursday for a crapshoot.

In case you hadn't heard, there's a city election in May (ballots drop in April), and candidates want their names to appear first on the ballot. Randomly selected pieces of folded paper dictate the order of names for each race -- mayor, city council, auditor and clerk -- so Thursday was like a political version of Mega Millions.

Since 1999, half of the candidates listed first in contested municipal races either won the seat outright, advanced to a runoff election or won the runoff, according to an analysis of old ballots by Denverite. (Runoffs occur when no candidate gets half the vote in the general election. The top two finishers compete a month later.)

Seventy percent of runoffs were won by the person whose name appeared first. That's 14 of 20 elections going to the top name.

This is not an article about how everyone at the top of the ballot will win. So many other factors account for who wins, like fundraising, name recognition and incumbency. This article is about how maybe, possibly... What if it actually matters?

David Sabados thinks it does. He's running to represent northwest Denver's District 1 and also happens to be a professional political consultant.

"There have been a few studies that show the top line and the bottom, actually, of contested races tend to fare better," Sabados said. "There's data on it, I believe in data, so obviously I'm hoping for a top line like my six opponents here."

A 2004 study by Jonathan Koppell and Jennifer Steen examined a New York City election in which the order of names changed depending on the precinct. In about 90 percent of the contests, voters chose candidates listed first more often than when they held a "lower" position, the study found.

A 1975 study Delbert Taebel produced similar conclusions, but found name recognition trumps name order.

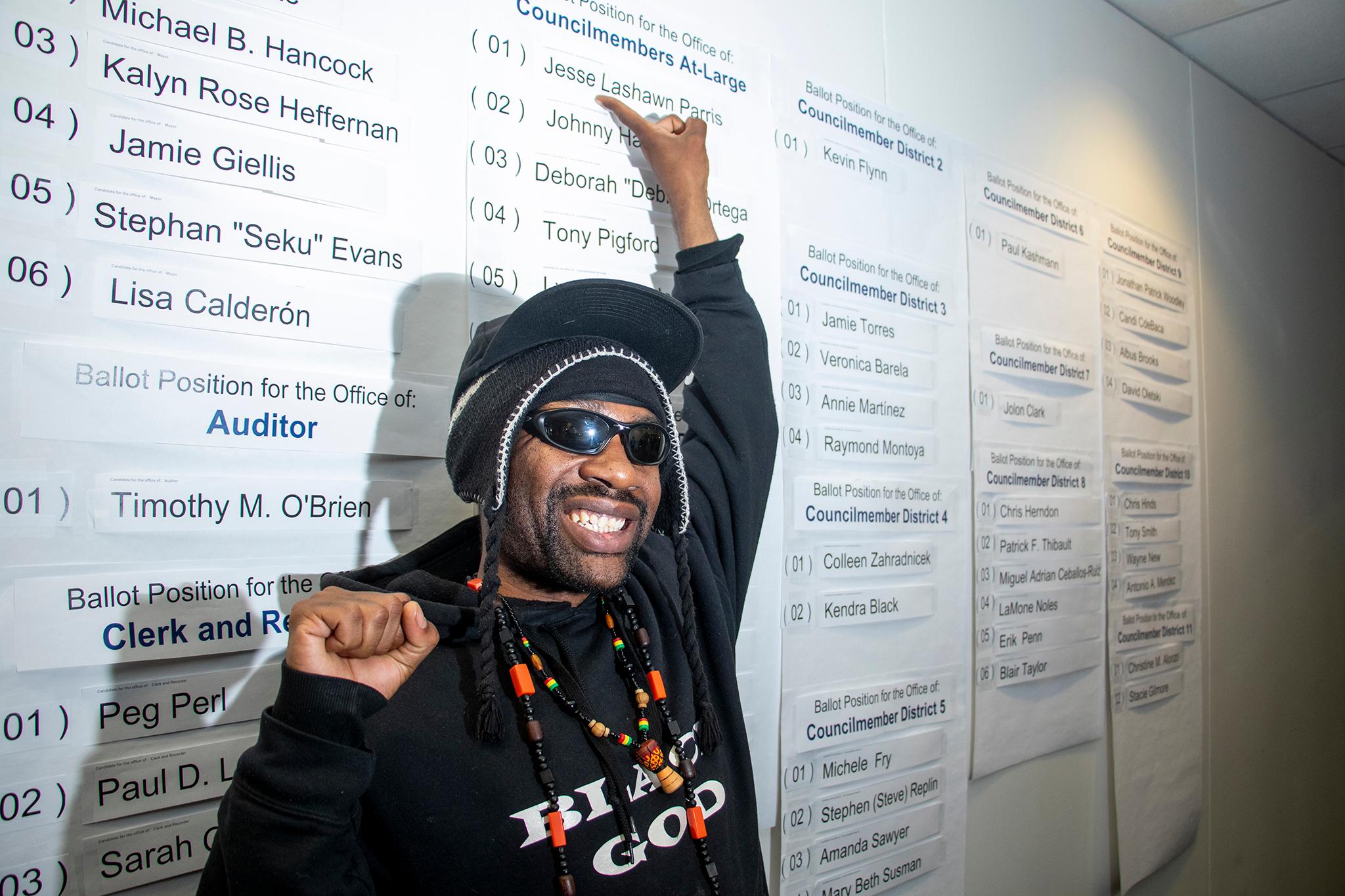

The voter might believe that a candidate earned that top spot and equate that with positive feelings, Sabados posited. He received fourth place out of seven.

Jamie Giellis, who is running for mayor, did not completely buy the importance of the top name, but changed her tune slightly after hearing about the 70 percent success rate in runoffs since 1999.

"It is a little surprising but I also think we're talking about a race against an incumbent that could be slightly different, where people who are looking for an alternative are gonna go for that alternative," Giellis said.

"Of course it matters," said mayoral candidate Stephan Evans, better known as Chairman Sekú, referring to the top of the ballot. He couldn't say exactly why, but claimed it would not matter.

"I'm gonna win flat out," he said.

You can see the results of the lottery at Denver Elections' Twitter page.