Denver 2040 will look different than Denver 2019, and now there's an official playbook for that future city.

On Monday night, the Denver City Council passed Blueprint Denver, a 300-page document that guides what gets built where and aims to cure Denver's car addiction while curbing displacement from gentrification. The plan envisions a city of "complete neighborhoods" with goods and services easily reachable by foot, bike and transit to abate solo driving -- and the cost and pollution that come with it.

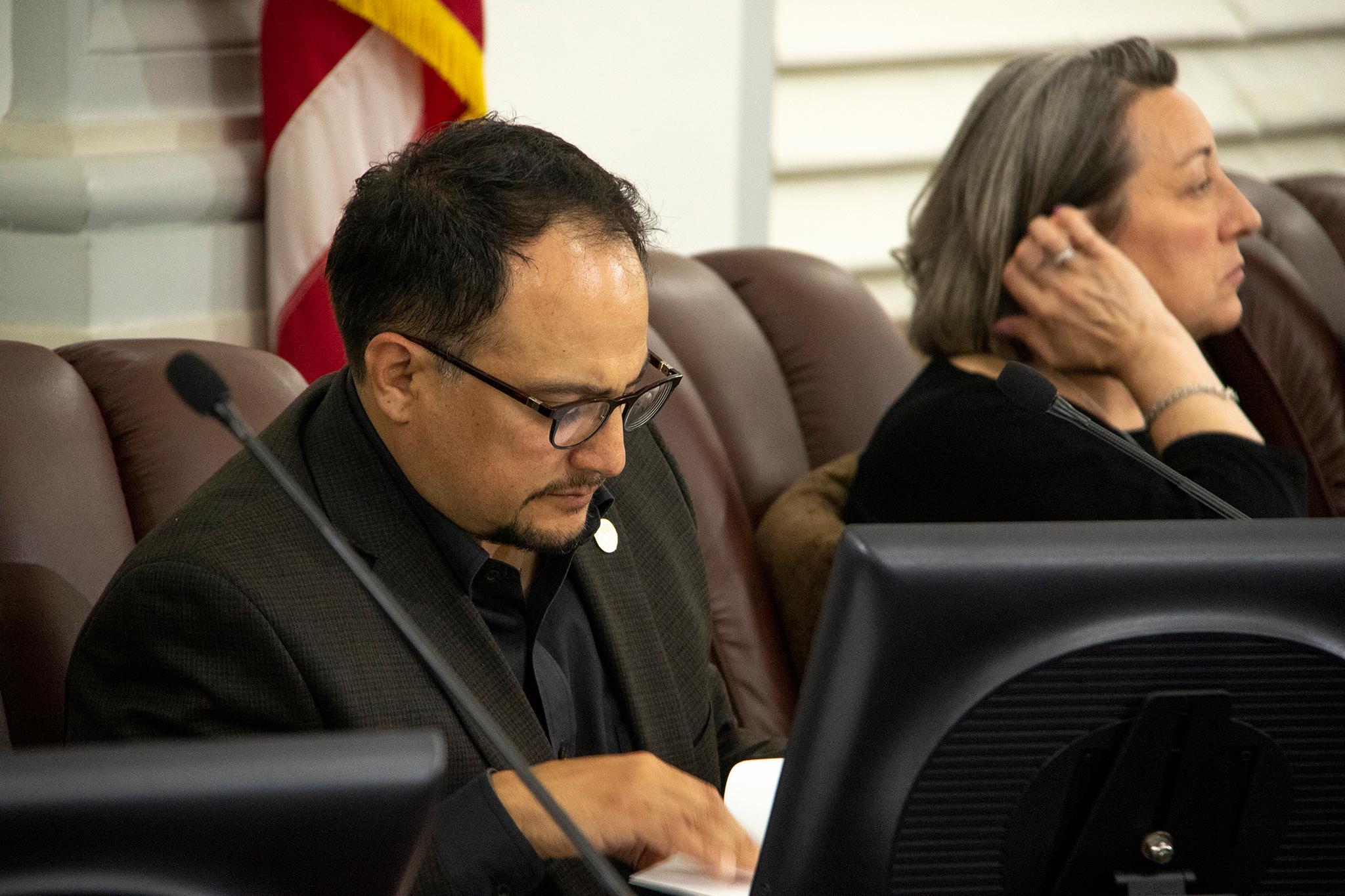

Council members approved the plan 10 to 2 with Councilwoman Debbie Ortega absent, and Council members Kevin Flynn and Rafael Espinoza dissenting.

Blueprint is not regulatory -- it will inform future policies and plans like a thesaurus informs language.

Here are the big recommendations in a nutshell, but there are a lot more policy goals in the full document:

- Allow more density in traditionally single-family neighborhoods, like accessory dwelling units (also known as granny flats), duplexes, four-plexes and townhouses, to boost the "missing middle" housing stock

- Concentrate density around frequent transit; new, big density changes should coincide with new, big transit investments

- Tie the right for developers to build taller buildings with a requirement to build affordable housing

- Track how public investment negatively affects low-income and minority residents

- Design streets to prioritize a hierarchy of people that puts pedestrians on top and solo drivers last

- Create new design quality standards; create a board that reviews building designs in high-profile areas like downtown

City leaders hope to curb displacement from gentrification by adding a more diverse housing stock to more neighborhoods.

Blueprint revises a 2002 document by the same name that cast development into two broad categories -- "areas of change" and "areas of stability." The dichotomy was too simplistic, city officials now say, and funneled development into certain areas while leaving others virtually untouched.

Now, a mansion in a wealthy area like Washington Park could become four apartments, for example, letting people who aren't rich move into a previously unattainable neighborhood.

Kimball Crangle, an affordable housing developer and co-chair of the Blueprint Denver Task Force, said allowing more types of housing in more places will chip away at decades of institutional racism.

"We're saying red-lining might not exist the way it used to, but it still is prevalent in our neighborhoods," Crangle said. "Until we approach that head-on, we're gonna perpetuate the inequity that exists."

Some people dislike Blueprint because it adds density, others because there's an election in two weeks. Councilman Espinoza said "the how" is not there.

Forty-eight people spoke on Monday, the vast majority in favor. Those against it expressed concerns centered on density in single-family neighborhoods.

Espinoza called the guide "remarkable" but voted against it because it's too blunt a tool, he said, in areas that don't yet have more focused neighborhood plans.

"Paving the way without concurrent regulatory guardrails is environmentally irresponsible now, and intergenerationally unjust for Denverites," Espinoza said.

With the municipal election two weeks away, some political candidates and neighborhood groups have framed Blueprint as a manual for unfettered development that the Hancock administration created with paltry input from locals.

But supporters cheered the three-year process, which resulted in 25,000 contacts with residents, according to the document. A resident-led, volunteer task force authored Blueprint with city staffers and consultants over 20 three-hour sessions, guided by feedback from public meetings and surveys.

"When I began the process, I thought it would be pre-prescribed and that perhaps our roles would be perfunctory," said Angelle Fouther, one volunteer. "I would like to say that I have felt very proud to be part of this process."

No councilperson said the plan lacked public input.

"Requests for delay were based solely on timing and not based on specific language in the plan," Councilwoman Robin Kniech said.

Will Kralovec, a member of the housing advocacy group All In Denver, said, "The nearly three years of process has been expansive and inclusive. We also find it ironic that those voices asking for a delay, that the very land use and development patterns they find alarming will only be perpetuated by leaving in place the existing outdated Blueprint."

The legislative body also passed the Comprehensive Plan, a shorter document with a broader scope.