Data shows Denver saw a record number of drug overdoses last year as fatal drug overdose numbers dipped statewide.

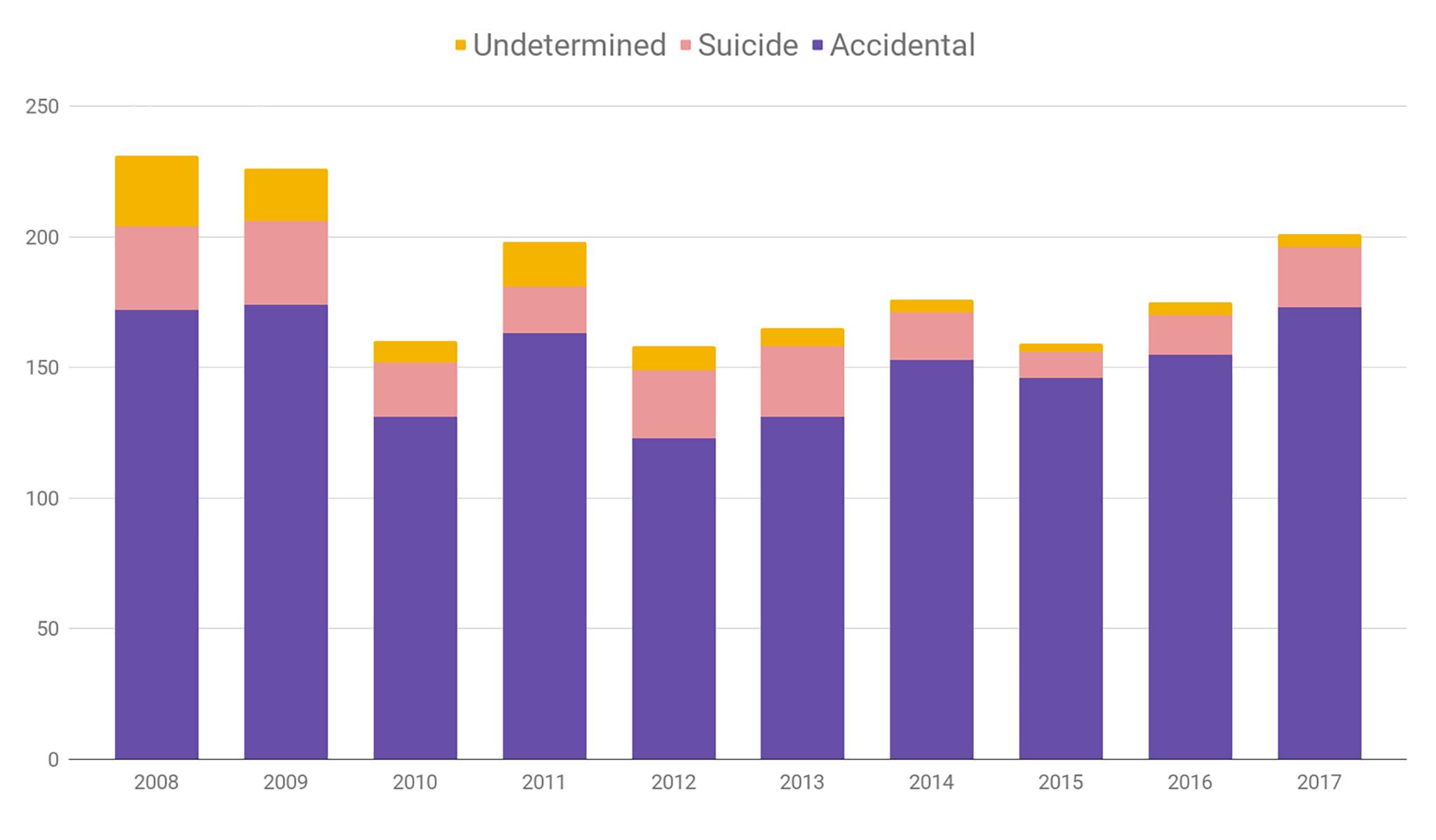

Figures provided by the Denver Office of the Medical Examiner show 209 people died of drug-related causes in 2018, an increase from the 201 people who died in 2017. The 2018 figure includes 183 drug-related deaths that are likely overdoses, surpassing the previous city record of 174 in 2009. The figures were finalized in April.

The reason those deaths are "likely" overdoses is that the manner of death was labeled "accidental," which is how fatal overdoses are labeled by the medical examiner. The remaining were listed as "suicides" (21) and a few were "undetermined" (5).

The city's own analysis of last year's drug deaths shows a wider, 10-year view of the trend that takes population growth into account. It shows the number of drug-related deaths is relatively flat.

"We're down, essentially. Although we do know we lost an additional eight lives, which we are not dismissing that at all," Lisa Straight, division director at the city's Community & Behavioral Health office, said. "Overall, we still feel like we're trending downwards."

Here's the number of "accidental" drug deaths (the ones that are likely fatal overdoses) compared to the overall drug deaths in the last 10 years, per the medical examiner's office:

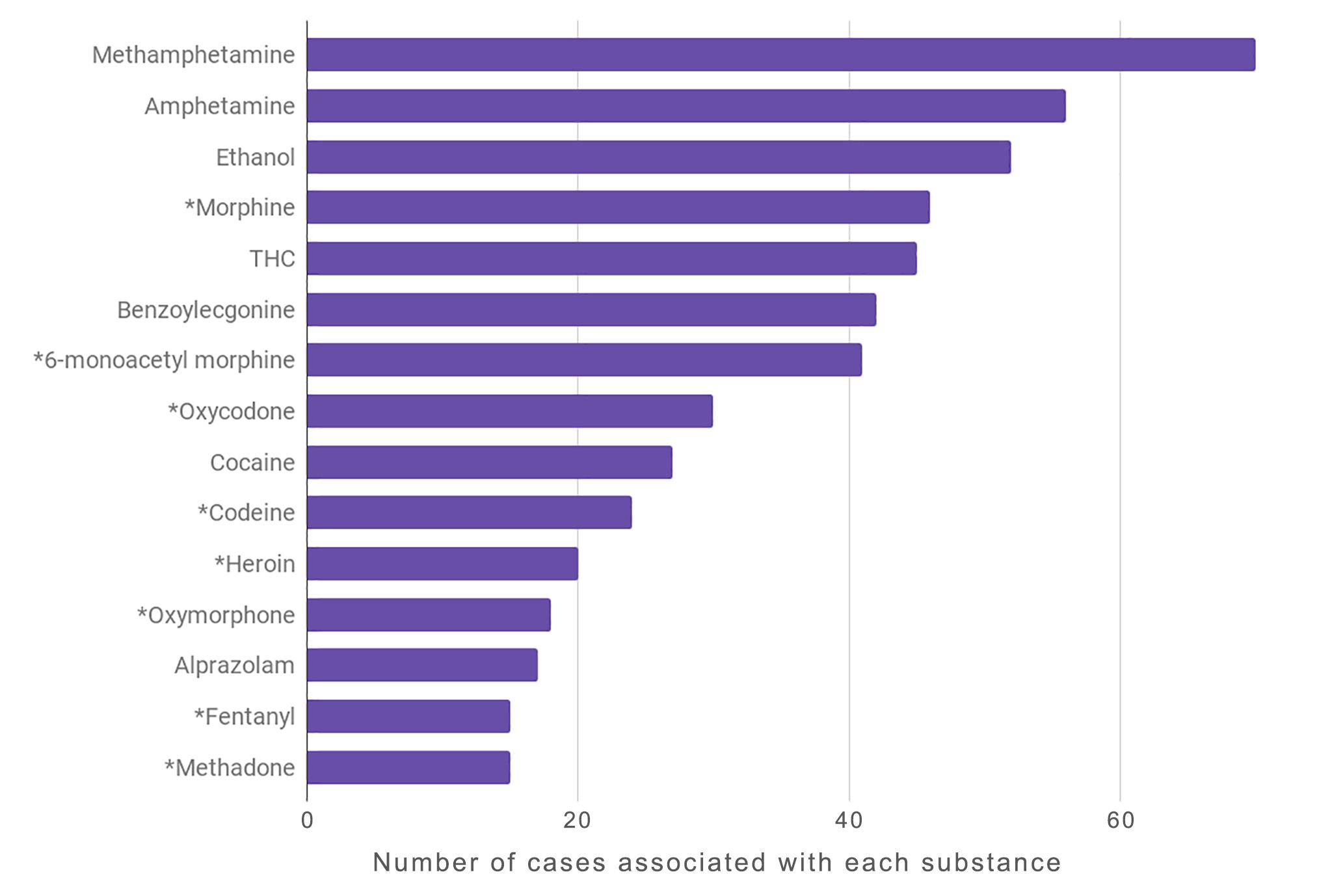

The city's analysis does point out an alarming increase in the number of people dying from overdoses involving methamphetamine. It also raises concerns about people using multiple substances at once.

Lisa Raville called the figures "disconcerting and disappointing." A local advocate for providing treatment for drug users, Raville leads the Harm Reduction Action Center near the capitol. The health center runs a syringe access program.

"It's honestly not surprising," Raville said recently. "We are in the midst of an overdose epidemic. And we have been shouting it from the rooftops for years. We haven't even plateaued yet."

"Eight more is too many more," Raville added.

At the state level, provisional data shows 972 people died from overdoses in Colorado last year.

The data was provided by the Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment. While these numbers aren't final and may change, the current total would be a decrease from 2017, when 1,012 people in the state died from overdoses. (2017 was a record year for the entire country.)

This year's provisional data includes 543 deaths involving opioids, down from 560 in 2017. If those numbers don't change, it would be the first time since 2012 that there was a decrease in opioid fatal overdoses in Colorado from the previous year. It also showed 317 deaths involving methamphetamine in 2018, up from 299 in 2017.

The data shows that while the city and state continue to grapple with drug deaths, the numbers are starting to taper off.

Jalyn Ingalls, a policy analyst at the Denver-based nonpartisan research firm Colorado Health Institute, has researched drug deaths in Colorado and said efforts made by the state are helping reduce overall drug deaths. The institute makes policy recommendations for state lawmakers, but they don't endorse bills.

Ingalls said moving forward she doesn't think the state will see annual jumps in the number of drug deaths compared to the increases seen from 2012 to 2017.

Here's what Denver is doing to address drug use.

Denver Substance Use Program Manager Jean Finn outlined some of the ways the city is working to help people with addiction or other substance use disorders. Some of that work is part of the city's strategic plan:

- A standing order from the state making it easier for people to get naloxone, a medication that reverses opioid overdoses. Several agencies provide it.

- Installing mailbox-sized needle disposal kiosks at four city-owned sites: Fire Station 4 at 19th and Lawrence, Governor's Park at Seventh and Logan, Lincoln Park at 13th and Osage and McIntosh Park outside of the Webb Building. They're scheduled to be installed this month.

- Providing grants to seven community-based organizations to acquire medication and other materials.

- Funding is in place to put together a kind of mobile health center, carried inside a bus or van, with various services inside including needle exchange and HIV testing.

- Putting together a team comprised of two new peer-support staff and a supervisor who can help people navigate the city's resources. The peer support staff include people in recovery. The staff is set to start work in May.

- An ongoing treatment on-demand pilot program launched last year in partnership with Denver Health. It provides a 24-hour intake site for anyone who's ready to start treatment. Finn said the program is going well. Between December and March, the program has had 171 people arrive at the ER and begin medication-assisted treatment. More than 70 percent of them were linked to additional care within two days.

"We know that stigma prevents people from getting services, both for mental health services and substance use," Finn said. She wants to let folks know that "many of the people doing this work have family or friends, or themselves, who have experienced ... these conditions."

Like the rest of the officers in his department, Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen carries naloxone. Protocol for officers responding to an overdose is to immediately render aid.

"We're taking it very seriously," Pazen said. "Ultimately, it comes down to us trying to support our vulnerable populations, our communities in need."

Another way the department is trying to provide assistance is with the LEAD program, which tries to divert people from jail and instead provides access to mental health services, job training and housing. The program offers leniency for people arrested for certain drug possession crimes.

Denver tried to launch a supervised injection site in an effort to address the crisis, but things didn't pan out.

The City Council approved a pilot program for a supervised injection site in November, one year after President Trump declared the opioid crisis a national public health emergency. His Department of Justice would later chastise the city for its attempt to open a supervised use site.

"(Council did that) right at the beginning of an election season, which was incredibly powerful, to show that they are so committed that they would do this during an election season," Raville said.

But the city's efforts were nullified at the state level. Without a complementary bill passed by the General Assembly, Denver's pilot program was essentially worthless. Efforts to introduce a bill were scrapped in February.

Raville felt disappointed. For one, a Democratic majority in both chambers seemed to indicate better chances than a similar bill introduced in 2018 that was rejected by Republicans. To make things even more frustrating for her this year, that bill was actually re-introduced, but it never made it past committee.

Legislation addressing the opioid epidemic has been introduced at the statehouse, including a bill approved this week that would increase resources for treatment.

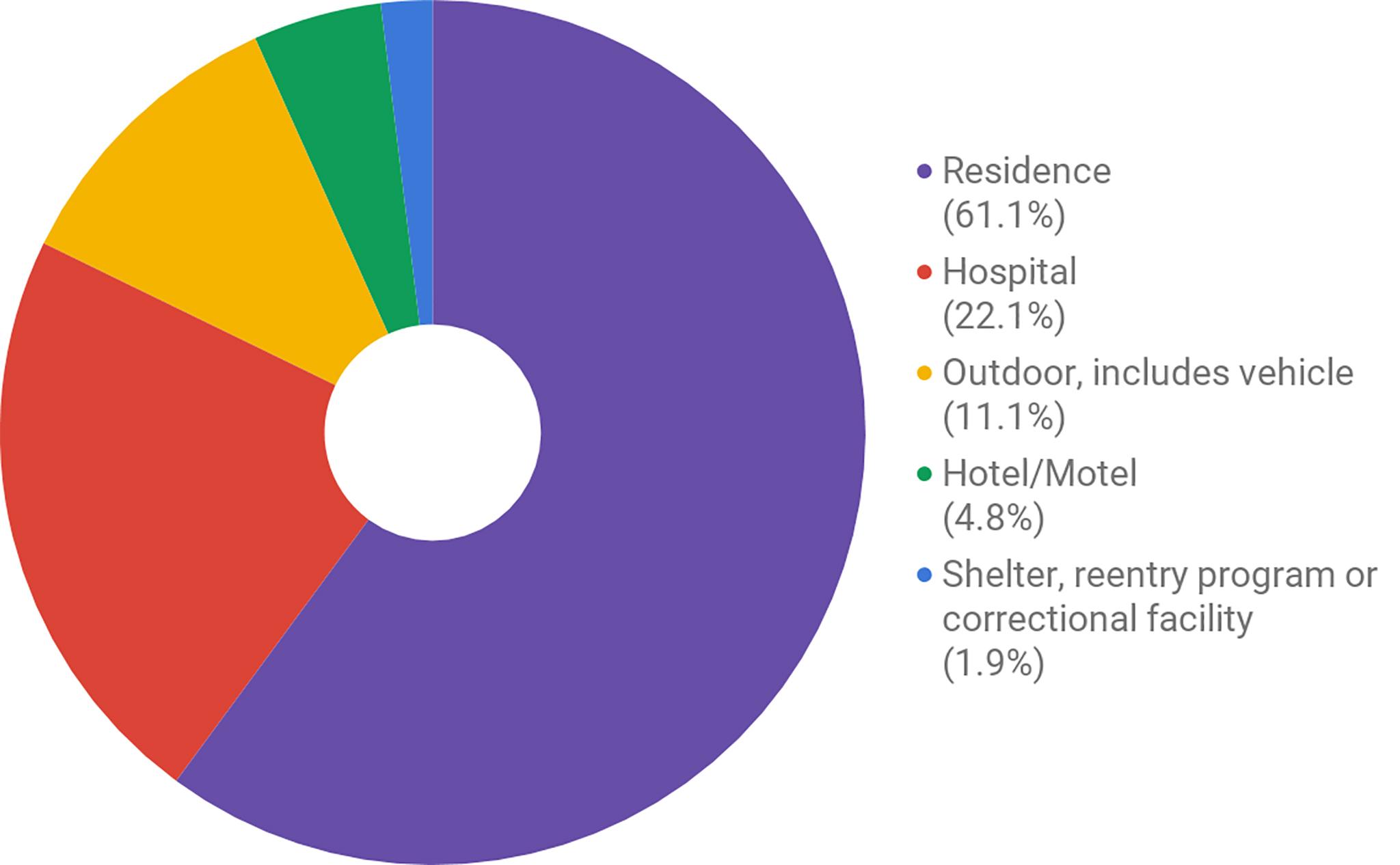

In 2017, 25 fatal drug overdoses were public, Raville said. In 2018, city data showed there were 23 fatal overdoses outdoors, including in cars, sidewalks and alleys. She thinks a supervised use site would have an immediate impact on reducing these kinds of overdoses.

She said it would also mean fewer "17-year-old baristas who are re-triggered every single day" when they find people overdosing in public bathrooms.

"This is not just about people who use drugs," Raville said. "This is about the larger community."