The architect who designed and developed the Cherry Creek Shopping Center was 90 years old when he got a call from a young colleague.

Jim Hartman, then 25, was working on renovations at the Paramount Theater, which Temple Buell also had designed. Hartman remembers the renowned architect, who would die four years late in 1990, graciously showing him drawings in his downtown Denver offices. They talked, among other things, about how it felt to see work demolished. Buell, whose firm designed hundreds of projects, told Hartman he was disturbed when he first learned of some of his buildings being razed to make way for new development.

But "after awhile he started to realize that was social change," Hartman said. "He didn't take it personally."

Decades later, Hartman helped preserve the oldest Buell school still standing. Buell might have been okay with the disappearance of Fruitdale elementary in Wheat Ridge, a suburb of 31,000 residents just west of Denver. But generations of former students felt differently. And the city and the Wheat Ridge Housing Authority saw transforming the building into 16 apartments -- five set aside for households earning no more than 60 percent of the area median income -- as a way of both showing respect for the past and looking to the future.

The $5.8 million Fruitdale School Lofts project has won awards, including this year from History Colorado, steward of the state's cultural and heritage resources, and the Urban Land Institute, which recognizes models of best development practices.

"Fruitdale's redevelopment is the first adaptive reuse project of its kind in the city of Wheat Ridge," City Manager Patrick Goff said in a statement celebrating the Urban Land Institute win. "Fruitdale School Lofts provides our city with an example of how to create sustainable and affordable housing in a re-purposed historic landmark."

For Gary Gorman, a 70-year-old lifelong Wheat Ridge resident, Fruitdale is personal. He attended in the 1950s from first through sixth grade.

"The teachers, they were so nice," Gorman said. "I repeated sixth grade because I fell in love with my teacher."

Gorman spoke in the dining room of a brick family home built in 1900 that is the headquarters of the Wheat Ridge Historical Society. Volunteer Janet Bradford, whose mother was born in the house, had just pulled a cardboard box of Fruitdale documents from the society's archives. Correspondence between Buell and the school board in the late 1920s. Photos from the 1930s of PTA officers who included Bradford's grandmother. Birthday cards students drew to celebrate a school anniversary in the 1970s, when there was talk of closing. A girl named Nancy wrote in careful cursive on lined paper that shuttering Fruitdale "will make many people very sad and unhappy."

Lauren Mikulak, who doubles as planning manager for the city of Wheat Ridge and staff for the housing authority, has more than once heard from a city resident about his or her days as a Fruitdale pupil. One passerby invited himself on a tour she was giving after the lofts opened and pointed out his younger self in a school photo preserved as part of the building's decor.

The personal connection so many in town feel is "part of the reason the building got saved in the first place," Mikulak said.

Fruitdale's reimagining as housing is seen as a first step to more investment in the area, Mikulak said. Her department has started to see other small investments and inquiries about projects on the stretch of 44th Avenue where Fruitdale sits along a major bus route and not far from the Wheat Ridge stop on the G Line, the newly opened train service to Denver's Union Station.

Back in 1883, when Jefferson County School District No. 32 was formed, two private citizens donated land for a one-room log schoolhouse that was built the next year, according to a brochure historical society members compiled in 1984. The log structure was replaced in 1901 by a two-room brick building that was destroyed by fire in 1926. Enter Buell, a Chicago-born World War I veteran who had arrived in Denver just a few years earlier and opened an architectural firm that would at one point be the largest in the Rocky Mountain area.

Buell's understated, two-story brick structure with a flourish of a masonry roof parapet was completed in 1927 and would serve students like Gorman and Nancy for five decades. It was closed to young students in 1978 because of shifting population trends, but stayed in use as an adult education center. The school district finally decommissioned it in 2007 and by 2011 was considering demolition. The Wheat Ridge Housing Authority stepped in to buy the school, even though it had questions about the financial feasibility of turning it into housing.

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2013. The housing authority, meanwhile, struggled to find development partners and a plan. Planner Mikulak said one feasibility study said the building should be demolished because the plot was worth more empty.

"Our (housing authority) chair went to Fruitdale, so that really hit close to home," she said.

In 2016, the housing authority entered into a public private partnership with Hartman's development company and the city. Mikulak credited Hartman for persevering despite continuing difficulties finding a financial solution. She thinks his early meeting with architecture icon Buell was key.

"I sincerely believe that's the only reason he stuck with the project -- because he'd met Temple Buell and felt responsible," she said. " It's one of the most complicated projects I've worked on. But one of the most rewarding as well."

Financing was a quilt of grants, loans and historic, federal, local and solar tax credits.

A ribbon-cutting ceremony opened the lofts in late 2017. Since then Hartman and others involved have been on a speaking tour of sorts, helping preservationists, developers and others "understand the various aspects of this kind of adaptive reuse," Hartman said.

It can be done "if people have the passion and can cobble together the financing," Hartman added. "Those are the two hard parts."

The Wheat Ridge Historical Society still pulls out antique apple presses for an annual cider festival. The Fruitdale Lofts' landscaping references that history with pear, crabapple, apple, plum and cherry trees and blackberry bushes. Out back is another kind of farm -- a solar array that along with more panels on the roof mean tenants' utility costs are a third of what they would be in a traditionally-powered building. Electric car charging stations in the parking lot can be used for free by tenants and by teachers and parents at a pre-school next door.

The building's first use is recalled in the entrance and main hall.

"It's really an educational gallery," Hartman said, standing in the hall amid placards on preservation, sustainability and architecture.

"And that's Mr. Buell about when I met him," Hartman said, gesturing to a plaque that includes the architect's biography and photo.

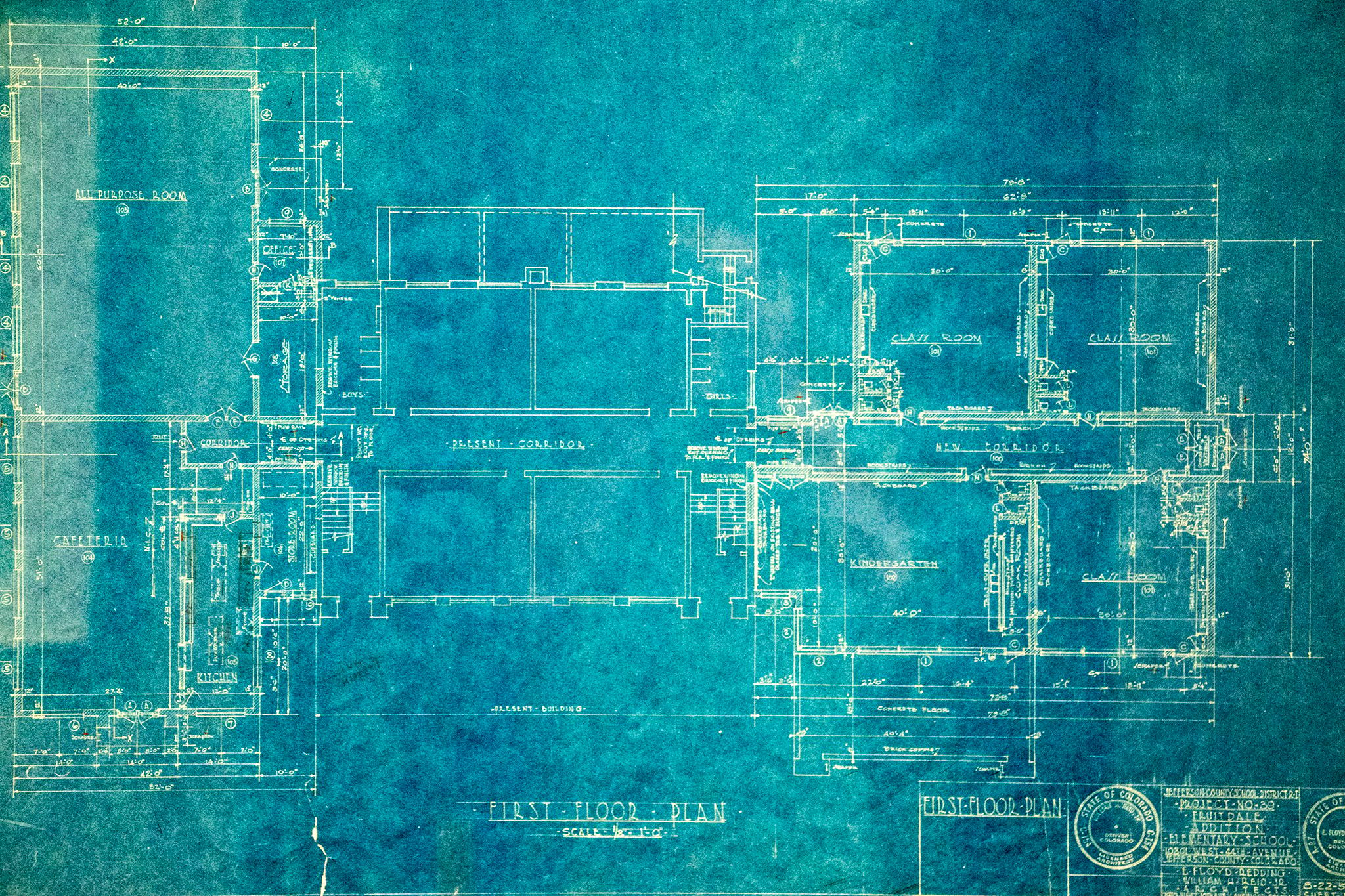

At one end of the hall sits a porcelain drinking fountain. Overhead are mixing-bowl shaped light fixtures copied from originals Hartman spotted in the corner of a vintage photograph. The design team pored over images and architectural drawings at the Wheat Ridge Historical Society as well as at the Denver Public Library's Western History Collection.

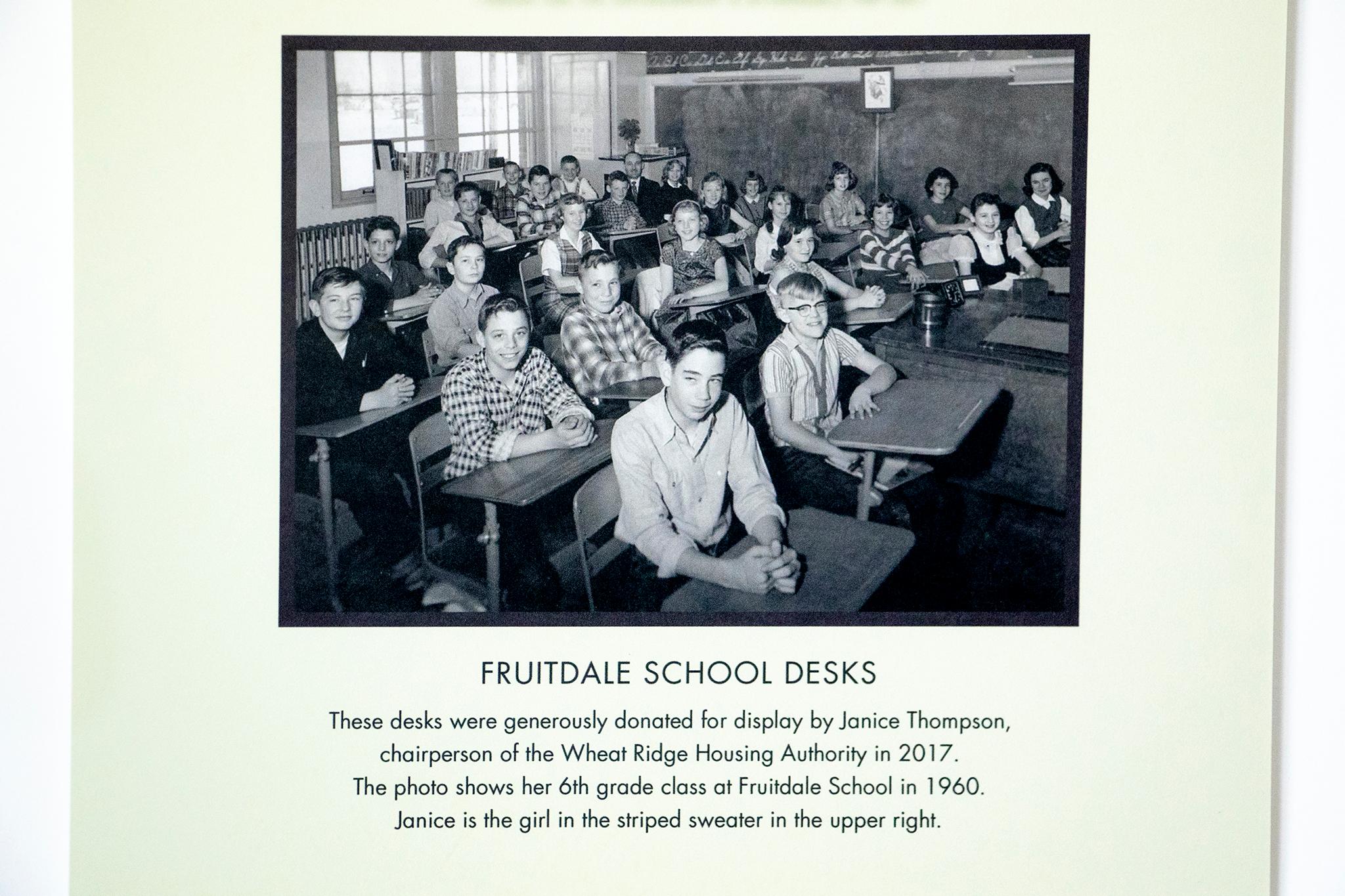

At the top of the stairs, bathed in natural light from Buell's skylight, sit two school desks donated by Janice Thompson, the Fruitdale alum who chaired the Wheat Ridge Housing Authority when the school project was being developed. A photograph on the wall behind the desks shows Thompson in her fifth grade class in 1960.

Gray tones bathe the walls, floors and cabinetry in the apartments, no two of which are alike. Ceilings are high. The Rockies dominate the views to the west from 1920s panes behind energy-efficient storm windows.

"We just worked and worked on the space plan so that even though they're pretty small on a square footage basis, the feel big," Hartman said.

Mikael Secrest has a two-bedroom in what had been the gym, an addition in 1954 that was not designed by Buell. The gym's original glazed tiles cast a pleasant green light over his sitting room. A basketball backboard was preserved as a decorative element. Other apartments have blackboards on which tenants keep their grocery lists.

Secrest attended Fruitdale and once played basketball in the gym. He said it was "weird" to be living where he once played, but he enjoyed showing visitors around.

Gorman, who had reminisced about Fruitdale at the historical society, didn't answer directly when asked what he thought of his school becoming housing. Instead, he said: "I'm happy they didn't tear it down."