Voters resoundingly rejected an attempt to overturn Denver's urban camping ban.

Initiative 300 on Tuesday's municipal ballot targeted an ordinance adopted by City Council in 2012 that made it illegal "to reside or dwell temporarily in a place, with shelter." Even a blanket is deemed "shelter" under the ban, which covers such activities as eating, sleeping or storing personal possessions in public. Initiative 300 also had in its sights another ordinance barring people from sitting or lying downtown except for overnight.

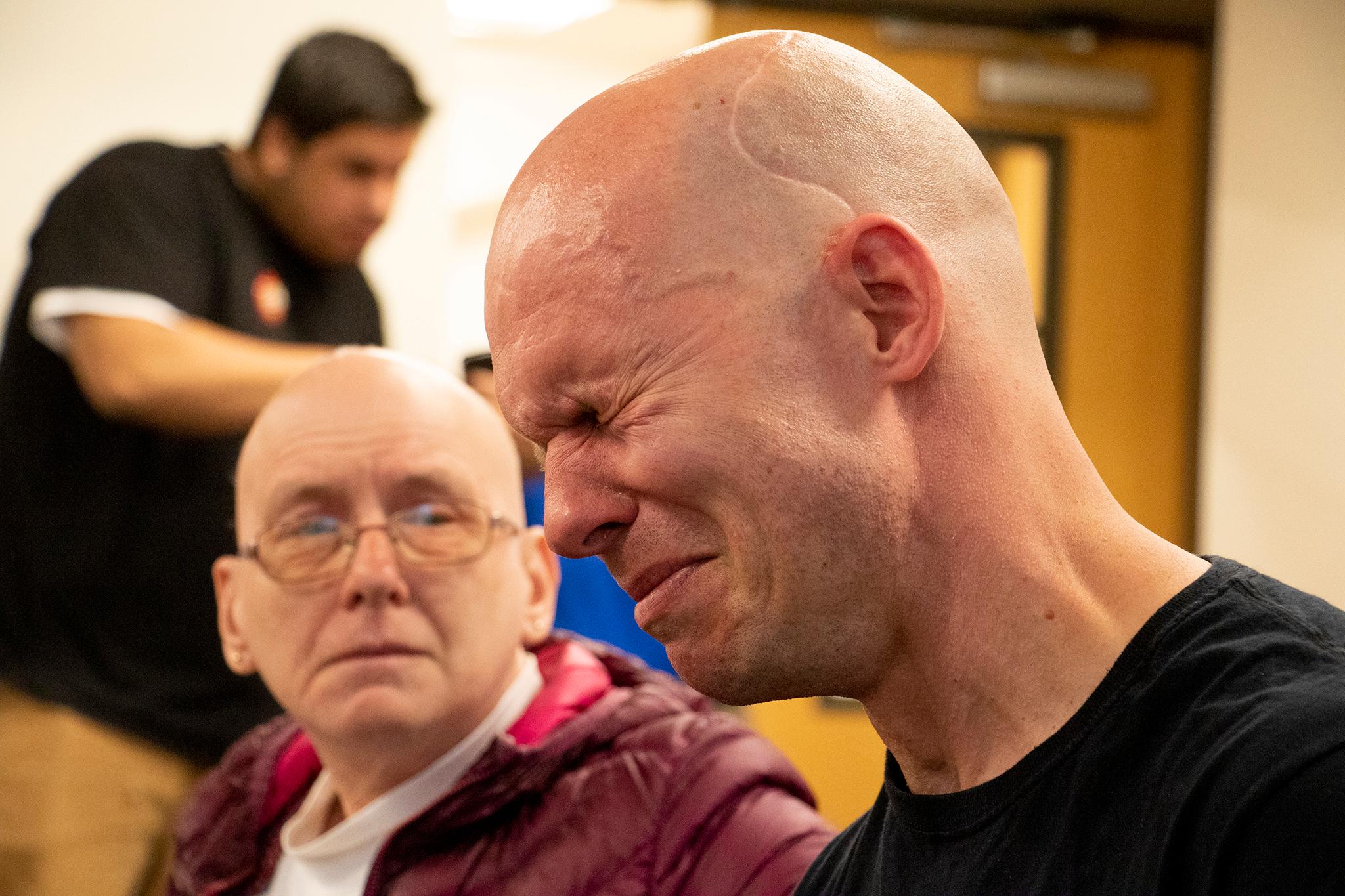

With more than 100,000 votes counted by 8:30 p.m., the "no" votes were leading about 84 percent to 15 percent. Somber members of the 300 team, gathered over pizza in a conference room in an office building in Cole, acknowledged the gap was insurmountable.

The proponents had portrayed 300, also known as the Right to Survive, as a measure to safeguard the basic rights of people without homes as the work to end homelessness continued.

Opponents focused on what they saw as the possible consequences: a dangerous undermining of Denver's ability to maintain order and sanitation for all who use the city's public spaces. Homelessness organizations that provide shelter, health and other services were wary as well, questioning whether 300 could be read so broadly as to interfere with their efforts to help people in need.

"That just goes to show you what money can do," said Jerry Burton, who campaigned for 300, attributing the loss to the opposition group's war chest.

Together Denver, led by prominent business and public policy figures, raised more than $2 million to fight 300. Burton's Denver Homeless Out Loud raised about $100,000. Denver Homeless Out Loud's leaders and members include people like Burton who live on the streets or who have experienced homelessness.

Roger Sherman, who managed the no campaign and is with the prominent public policy firm CRL Associates, said in a statement that he hoped the people of Denver would continue to look for "practical approaches" to homelessness.

"While most voters agreed that Initiative 300 was not the right path forward for Denver, this is not the end of the discussion," Sherman said. "There is more we can and should be doing, as a community, to ensure Denver is a safe, welcoming and supportive place for everyone."

A voter who gave only her first name, Alison, dropped off her ballot with her no on 300 vote about 15 minutes before polls closed at 7 p.m. She said she was voting primarily because of 300.

"I think that we can do better than having people live on the streets," she said, adding she feared Denver could end up like San Fransisco or her home town of Los Angeles.

"I have stepped on vomit on the sidewalks in San Francisco," she said.

Steve Dzuba also voted late, but he voted for 300. He said he had been homeless himself before the camping ban and believes outreach workers would not have found and helped him if he had felt pressure from police to keep out of sight.

Initiative "300 is a good thing," he said.

Before turning to voters, Denver Homeless Out Loud had tried and failed repeatedly to get the state legislature to overturn the camping ban. Terese Howard, another organizer for the group, said it would now be returning to the legislature and seeking recourse in court and city council to try to get the ban overturned. All Denver City Council seats were also on Tuesday's ballot, though three were uncontested.

"We're back at council the minute we have a new council," Howard said.

Together Denver had asserted 300 would eliminate park curfews, which Denver Homeless Out Loud said was not the case. Together Denver portrayed 300 as threatening such popular recreational areas as the Highline Canal and the approach to the Denver Art Museum, and raised the specter of Los Angeles.

While acknowledging it was court rulings, not a vote, that have hampered that city's ability to curb urban camping, Together Denver campaign material referred to "drug use, violence, prostitution and arson" as common along Los Angeles's Skid Row.

"The human waste, discarded food and trash associated with the encampment has attracted rats and fleas and created a public health crisis, including a typhus outbreak," it continued.

Denver Homeless Out Loud says nothing in 300 would have kept officials from continuing to maintain sanitation and order in the city or from providing bathrooms and other infrastructure.

Groups that serve the homeless had criticized Together Denver both for spending so much to get its message out, and for mounting a campaign that some saw as vilifying those living in homelessness. Together Denver policy director Cody Belzley responded that her organization was committed to making voters aware of what it saw as the risks of 300.

"We're trying to be very sensitive and thoughtful in the way we talk about those risks," she said. "We're working very hard to try to run a compassionate, thoughtful and honest campaign."

Together Denver's campaign included testimonials from people who had experienced homelessness who talked about the dangers of living on the streets. Opponents of the measure who distanced themselves from Together Denver expressed concern that by allowing camping, Denver would be giving up on doing more to end homelessness.

City Councilwoman-at-large Robin Kniech, who rejected the camping ban in 2012 and continues to oppose it, has called for improvements in the shelter system, more options for people who won't or can't use shelters and more investment in supportive housing. Kniech won re-election Tuesday.

"I'm not participating in any campaign around 300, because neither side is talking about proven solutions or standing up to advocate for the funding and policies we need," Kniech added in a recent essay emailed to supporters and posted on her website.

In an opinion column published in April in the Denver Post, the executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado called for a yes vote on 300 "because it ends the Denver camping ban and other ordinances that criminalize homelessness."

The ACLU's Nathan Woodliff-Stanley also noted that the slogan of the opposition was "we can do better."

Doing better, Woodliff-Stanley said, "starts with recognizing that human beings shouldn't lose their human rights just because they've lost their home."

But John Parvensky, the longtime president of the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, wrote in the Post that he feared 300 would "have unintended consequences and will not resolve the complex crisis we are experiencing in Denver."

"I believe that a lasting solution requires an adequate supply of affordable housing dedicated to the homeless and a robust emergency response system that has safe, appropriate and accessible emergency shelter until long-term housing can be obtained," said Parvensky, who also called on the city to stop enforcing the camping ban unless public health and safety is threatened.

According to data compiled by Denver police, between June of 2012 and this January, officers on more than 12,000 occasions have approached individuals and groups in parks and other public spaces to enforce the camping ban. It's rare for even a written warning to be issued, let alone for an officer to make an arrest. The 2012 law stipulates that police should prioritize getting people to comply with the law simply by asking, and should try to get help for those who need it rather than citing them.

Police say the low number of warnings, citations and arrests was proof they were carrying out City Council's intentions of trying to help those in homelessness, not criminalizing them. But Denver Homeless Out Loud says just because the camping ban doesn't always lead to tickets doesn't mean it's productive.

Denver Homeless Out Loud worked with researchers at the University of Colorado Denver to survey 484 people experiencing homelessness in Denver about the impact of enforcement of the camping ban. According to a report released in April, nearly three-quarters of those surveyed reported at least one encounter with police in the previous year because they had been sleeping, sitting or taking shelter in public. Of those, only 14 percent said they were asked if they needed help, and in just 3 percent of those cases was a social or medical worker called in.

"From this data, we see that contact with police rarely ends in delivery of social services, but far more typically ends in 'move along' orders and warnings to quit using blankets or other shelter from the elements," the report said. "Other common results are warrant checks, citations and arrests. It is a dynamic designed to disrupt the daily lives and emotional balance of Denver's homeless residents."