A new study from researchers at Denver's National Jewish Health surveying north Denver's air quality shows residents are often exposed to pretty good air, even though the area is often thought to be inundated with emissions from the nearby highways looming above.

The study did find, however, that their worst exposures were often inside their homes.

Dr. Lisa Cicutto enlisted the help of 19 residents to strap air quality sensors to their belts in three seasons throughout the last year. Now she and her team are presenting some of their results.

Particulate matter suspended in air has become the focus of research in recent years as sensing technology has become significantly smaller and cheaper. Most of these projects look exclusively at ambient air quality by planting sensors in static locations and observing changes over time. Denver is working on one of the largest networks of these kinds of sensors in the country.

But Cicutto's project brings a novel approach to the field and has the ability to suss out exactly when people might encounter bad air. The results suggest people living in north Denver might be most exposed when they're at home doing everyday activities.

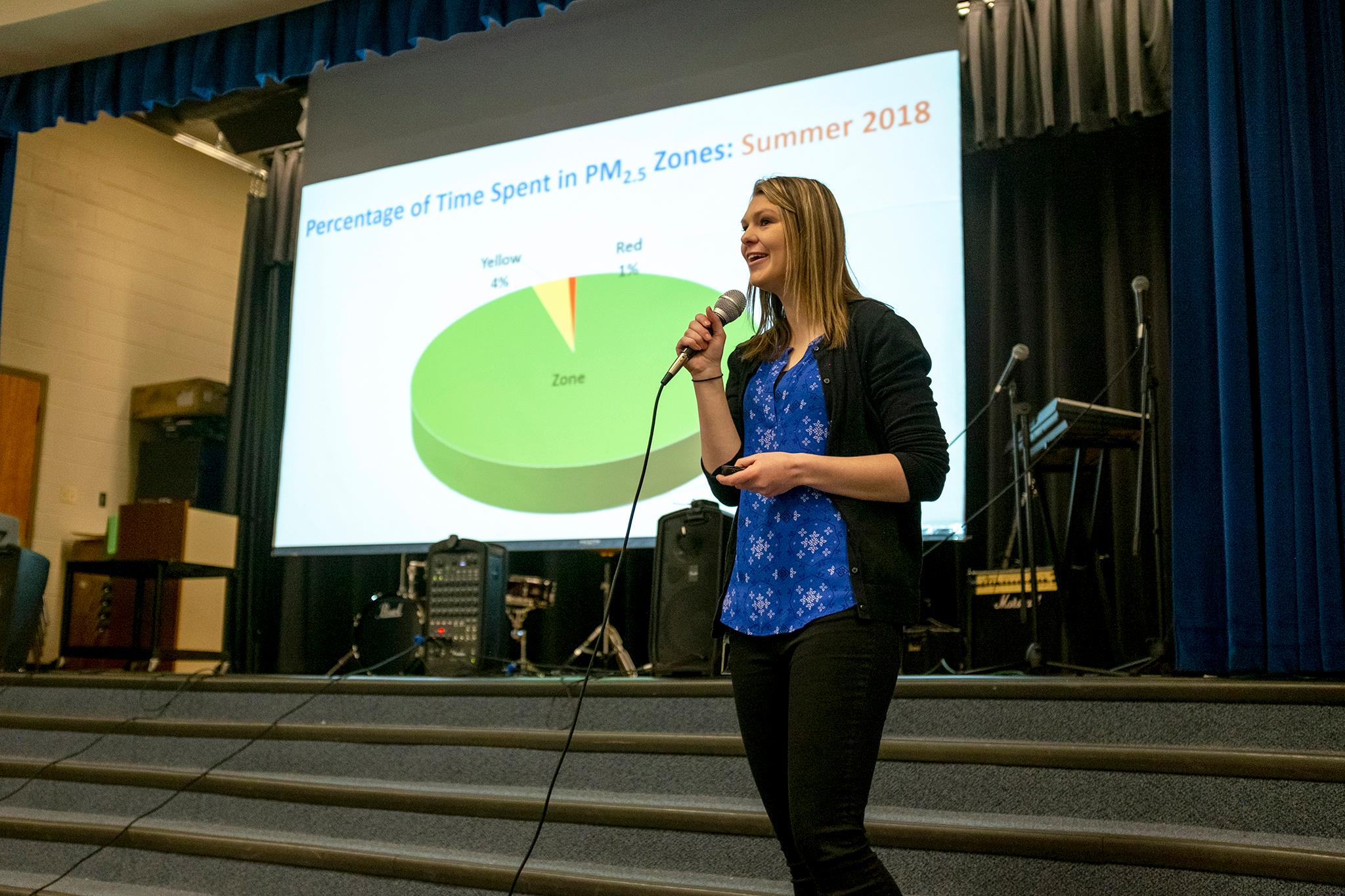

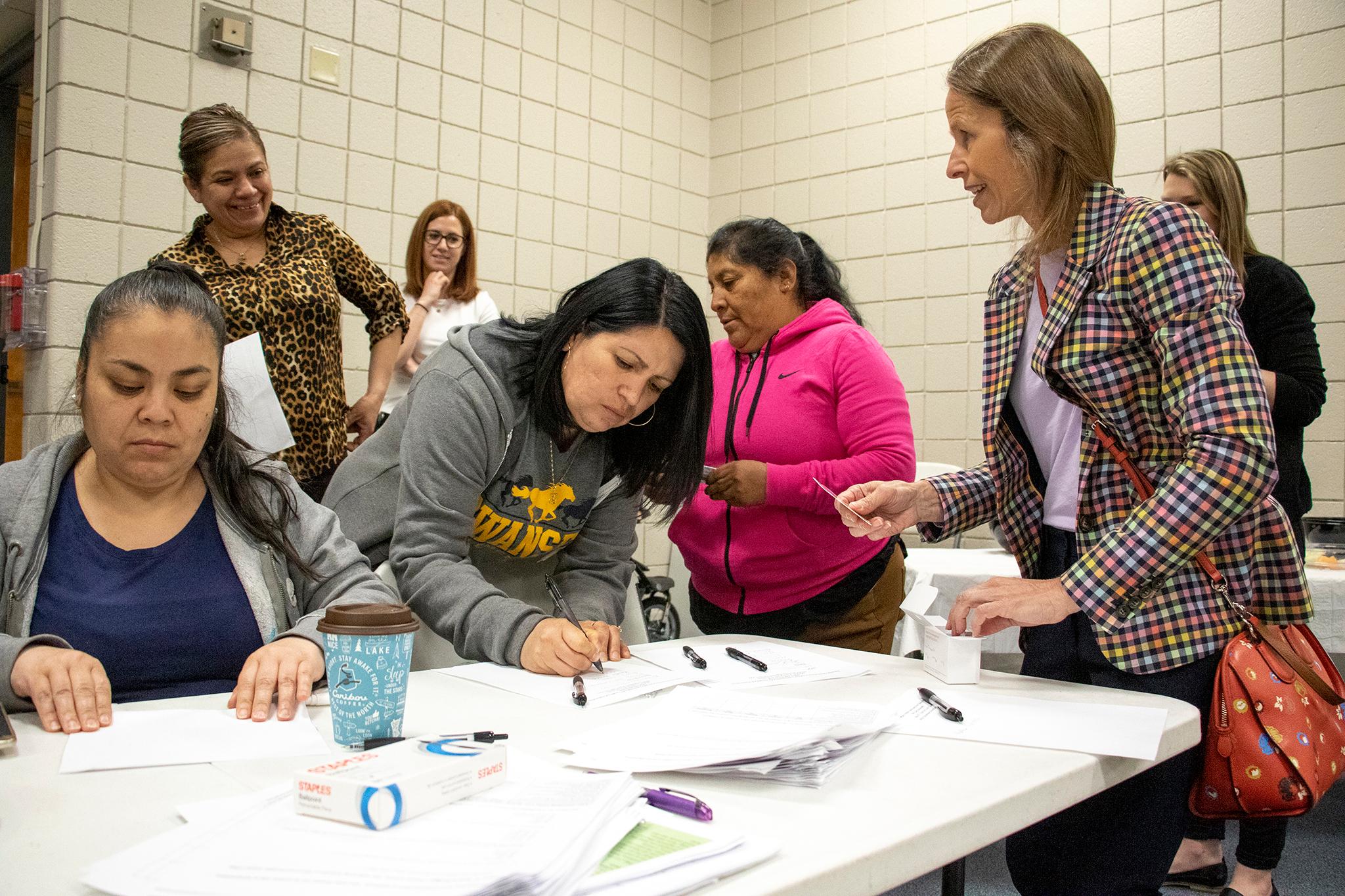

The project's goal is more than just understanding potential issues: Cicutto is also trying to figure out the best ways to communicate her findings to people as they help her gather data. She and her research assistant, Molly McCullough, visited Swansea Elementary this month to kick off the first in a series of informational discussions.

Through a Spanish interpreter, McCullough told a crowd of mothers that, last summer, the 19 people wearing monitors experienced what's considered "good air" 95 percent of the time. In winter, people breathed in the good stuff 91 percent of the time. In autumn, that number fell to 88 percent.

Participants carried notebooks and reported what they did throughout the day, which allowed the researchers to pin down what they may have been doing when the worst quality air was detected.

"Things like burning candles, cleaning," McCullough said.

Mowing the lawn and using body spray were also cause for exposure and, she added, "cooking was a really major one."

McCullough finished with a list of tips that people should keep in mind:

- Use vents if you have them while you're cooking (Cicutto added you should turn these on before you fire up a gas stove).

- If you don't have vents, open a window.

- Use your central air or heating systems as air fresheners, just remember to replace filters once a month or so.

- Make sure smokers and vapers smoke and vape outside.

- Avoid using candles.

- If you're on the highway or stuck in traffic, roll up your windows and activate recirculation mode.

"Here's a little catchphrase, it's probably not going to sound the same in Spanish," she said. "Dilution is the solution."

If you can get fresh air flowing, it will help cut down high particle concentrations.

The air isn't terrible, but inequity likely still plays a role in health outcomes.

A study in 2014 by the city showed that Elyria-Swansea and Globeville experience "a higher incidence" of chronic health issues like asthma and heart disease. The area has been described as the "most polluted" zip code in the country. Though that superlative is a little problematic, the neighborhoods have plenty to contend with. Two busy interstates looming over the neighborhoods are often thought to be behind it. Industrial facilities like the nearby Suncor tar sands refinery has also concerned community advocates.

While Cicutto's findings might appear to challenge this narrative, it's not so simple. She said her results don't vindicate the highway. Instead, they add nuance to a problem that's not well understood.

Exposure to pollution "all depends on where people go," she said. "A lot of the time was spent indoors."

Community-wide health issues occur when multiple issues begin "stacking on each other," she said. "It's the built environment, it's access to care," and access to preventative resources, too.

Air filters, for instance, can be expensive. The same person who can't afford to install a big vent hood over their stove may also be strapped for cash when it comes to buying monthly filters.

"Do I buy this medication? Do I feed the kids?" Cicutto said. "Or do they buy a filter?"

There's another issue in Elyria-Swansea at the moment: it's booming with construction activity as CDOT renovates I-70.

When McCullough suggested opening windows, one woman said, in Spanish, "We'll be taking the smoke out but then the dust will come in."

When she had the chance, Maria Espino raised her hand. Kenie Abeyta, a family liaison who works at Swansea Elementary, translated.

"She said it's almost next to impossible to eliminate a lot of that particulate matter," Abeyta reported in English. "Especially in this area, I think part of it is the concern with the construction right now."

Espino lives just two blocks from the ongoing I-70 work. After the meeting, she said she's noticed more dust in the air around her house and that her 18-year-old has been using his inhaler more often.

CDOT has air monitors around their worksites and protocols in place to shut down work if air quality breaks a certain threshold. While they've succeeded in keeping emissions below required limits, the project still is encouraging people like Espino to keep their windows shut. She's looking forward to the finished project, though the loud, dusty construction so far has been onerous.

The fact that some residents hesitate to open their windows might mean they're more likely to breathe in particulate matter. Cicutto said she suspects the reasons that summer exposure was better than fall or winter is likely that people are spending more time inside.

There's also some demographic information to consider.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control show that women over 18 are more likely than girls, boys or men to suffer from asthma. People who earn less than $75,000 per year are also are at a higher risk for the condition.

Cicutto's study might shed some light on why.

The crowd laughed when McCullough mentioned cooking was a major cause of particulate pollution.

"This is where you get out of cooking every day because it's not good for your health," one woman said from the back of the room. "Make sure you give us a note so we can show our families."