As testing for carcinogens is underway in a building at Metropolitan State University in Denver, public health experts said it can be difficult to link cancer to a place or environmental contamination.

The testing started after MSU officials were notified that four of its employees who worked in the West Classroom building were recently diagnosed with three different kinds of cancer. One died of lung cancer two years ago while two others have breast cancer. The fourth has liver cancer. A retired administrative assistant who worked in West Classroom for 20 years told CPR News that she knows of at least eight additional people who have also been diagnosed with various forms of cancer and worked in that building or the adjacent Central Classroom building.

Colorado's Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) said the agency is not involved in the testing at MSU Denver but is providing guidance to the school on how to interpret data that comes back. Test results are expected Thursday.

State toxicologist Kristy Richardson said cancer clusters are scarce. A "cluster" is defined as "a greater-than-expected number of cancer cases that occurs within a group of people in a geographic area over a period of time," according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"Cancer clusters are rare, especially those that are linked to environmental exposure," Richardson said. "We have not identified a cancer cluster in Colorado that we would attribute to an environmental exposure."

Dr. Jon Samet, dean of the Colorado School of Public Health, said it would be difficult to think of something that would cause what are three relatively different types of cancer at MSU, though he acknowledged he's still waiting to see results from the testing.

"It's still a little hard to just link up across these different types of cancer and say that something will be found in there that might be causing all of them," he said. "A lot of these clusters probably just occur by chance. Cancer is a common disease."

Samet said as people age, the likelihood of getting cancer increases. And if there are enough people in one place, it could be "just by bad luck."

Concerns about diagnoses rarely result in answers anywhere in the U.S.

While the CDC does not deal with cluster scares, a spokesperson from the agency said they get an average of three calls each month concerning cancer within specific communities. That's an average of 36 inquiries each year. CDC redirects these callers to local and state agencies. A CDPHE spokesperson said their agency gets "less than 10" of these calls every year.

But despite fear that specific cancers are overrepresented in some areas, it's extremely rare that calls to agencies result in answers.

Alison Adams, a University of Florida sociologist who studies how communities battle powerful industries after poor health outcomes emerge, said she generally doesn't have a "super rosy perspective" when it comes to finding out why communities may experience higher rates of specific diseases.

"Even in cases where it's very apparent, there's still a lot of disagreement and it's very difficult to make the connections," she said.

While natural disasters tend to unite communities, she said possible cluster issues tend to drive wedges within social groups. Residents often have to become "lay epidemiologists" by going door-to-door to tally up potentially related cases and use their informal research to keep these issues from fading away.

Adams pointed to Libby, Montana, where at least 1,000 people were sick at least 200 died from lung disease -- out of a population of 2,600 -- which was thought to be caused by industrial asbestos exposure. Those numbers come from 2009 estimates, when the EPA declared a public health emergency to provide federal healthcare assistance, the first time in the agency's history. Parts of the town were added to EPA's Superfund registry in 2002, which stemmed from vermiculite laced with asbestos mined by the W.R. Grace company.

Even though federal agencies recognized Libby's problems, W.R. Grace was acquitted in federal court of charges related to asbestos exposure in 2009. It took eight more years for the company to settle with community members in Montana district court. They agreed to pay $24 million in 2017.

But other cases have ended with less positive results for concerned communities.

In 1987, residents of Friendly Hills, a suburb south of Denver, raised an alarm that children were unusually dying and blamed the perceived issue on groundwater contamination caused by Martin Marietta Corporation's nearby aerospace tech operations. Community members filed a federal lawsuit against the corporation and Denver Water, but it was dismissed in 1990. U.S. District Judge Zita Weinshienk, who presided over the case, said in her dismissal that there wasn't enough information to link "overwhelming evidence" of soil and water contamination to health outcomes.

Insufficient correlations between health outcomes and environmental causes have long plagued communities concerned about cancer. It happens when state agencies investigate possible clusters as well as when communities fund their own private research. An ongoing scare involving thyroid cancer in Iredell County, North Carolina, which has three times more cases than state averages, is one such case where private research has still yet to find any solid answers.

Dr. Heather Stapleton, a thyroid cancer expert working on the Iredell study, said it's often hard to fund work on cancer's causes since money is often dedicated to cures. Of all the studies funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in 2018, just $2 million was invested in work specifically looking for non-genetic causes. More than $11 million was spent on treatment research. The NCI says they don't fund work based on a rubric of areas to study, they just fund the most viable research and let things shake out as they will.

CU's Samet disagreed that there's not enough known about cancer's causes.

"We've got a lot of the environmental causes of cancer pretty well nailed," he said, citing smoking and exposure to radon that is known to cause lung cancer.

Stapleton raised the same knowledge as an argument for a need for more study.

"Certainly we need more science here. Just look at the fact that we know smoking causes lung cancer," she said. "To me, it makes sense that other chemical exposures that occur in our daily lives, through normal behavior, could also lead to it. It's just a matter of understanding what those exposures are over time."

There is plenty of industrial history on the Auraria Campus to keep Metro State faculty thinking about cancer.

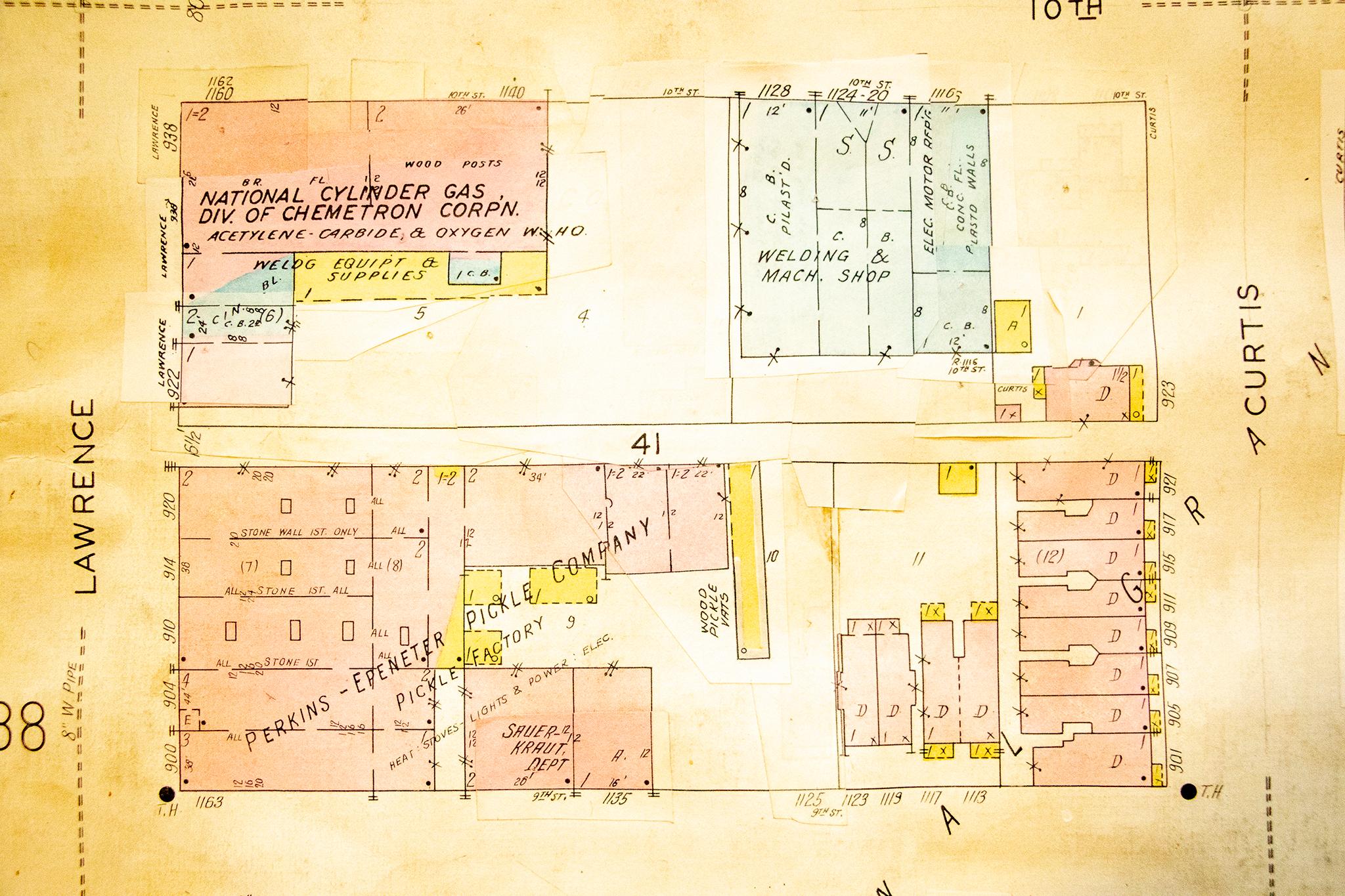

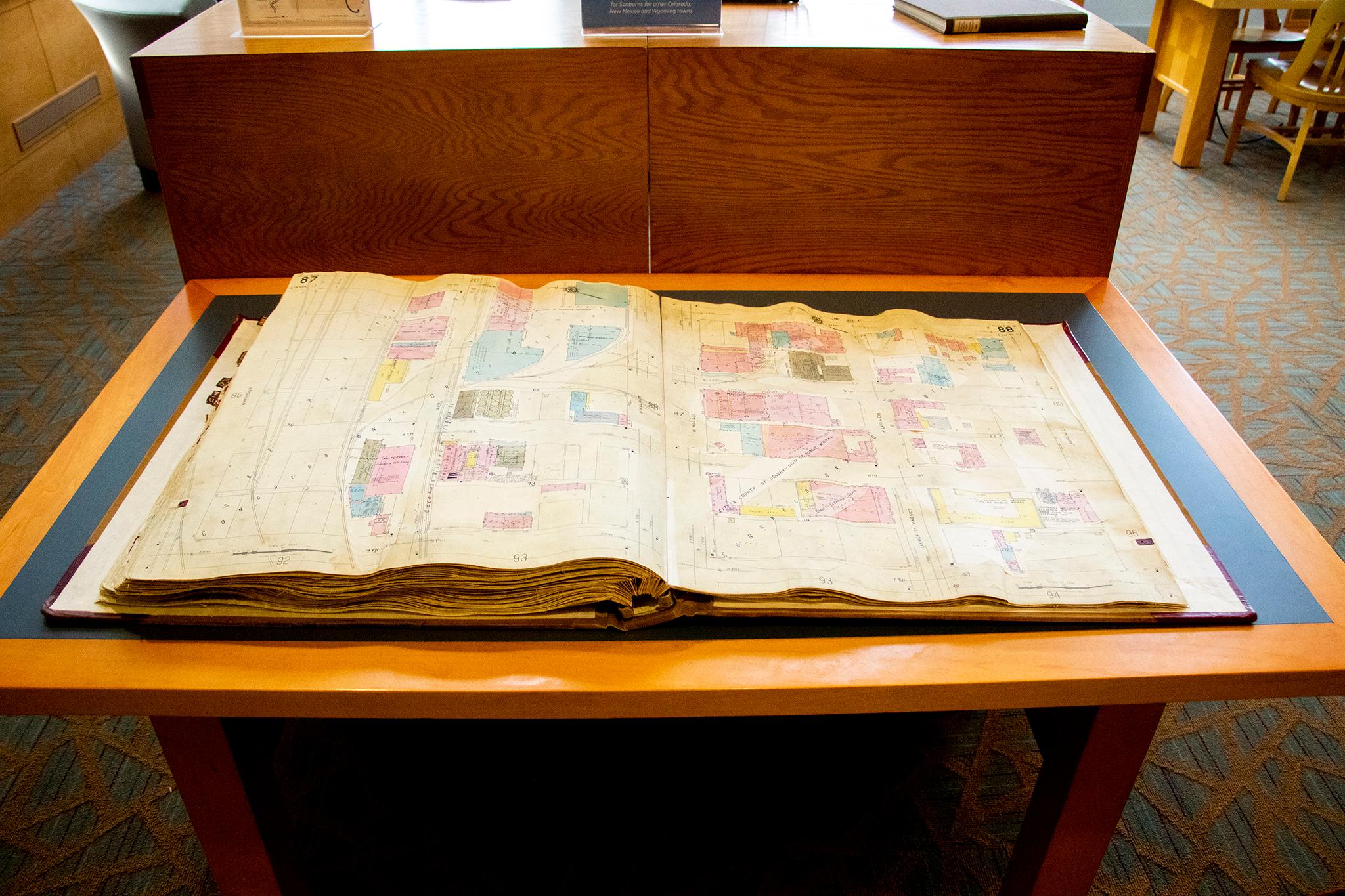

Again, the fact that multiple different types of cancers were reported among Metro State faculty means it's very unlikely that the cases are related. But a quick look at the Denver Public Library's old fire insurance maps shows plenty of industrial land use predating the universities there.

The West Classroom, which sits at the intersection of what once was 10th and Curtis streets, stands on a block that was once home to welding shops, the "national cylinder gas division" of the Chemitron Corporation and a pickle factory. A rat poison production facility once operated nearby at 10th and Wynkoop. The area was also peppered with industrial manufacturing operations and auto shops. The latter tend to cause known legacy pollution issues, especially when underground gas tanks were stored around old garages.

Concern over historic pollution occasionally surfaces in the metro area. It's not just for sites like Rocky Flats, which once produced weapons for the military. Residents have been actively resisting the closure of a huge piece of the I-70/Vasquez Boulevard Superfund site, which encompasses much of north Denver. Despite the fact that dirt in most residential yards there was replaced after lead and arsenic was found to have rained down from historic smelting operations, nonresidential areas were never remediated. Residents fear that new projects like the 39th Avenue Greenway construction might kick up contaminants that still remain in the soil.

The Denver Department of Health and Environment has said that they employ "materials management plans" to deal with any suspect soil during new public development projects and that humans are not generally in danger unless there's a clear "pathway to exposure," like if children eat contaminated dirt. But according to Zachery Clayton, a public health manager with the agency, "there were few regulations requiring cleanup of contamination left in soil" back in 1973 when construction at Auraria broke ground.

Samet added there could be other health concerns besides cancer that could be caused by poor building maintenance.

While MSU has begun testing at the West Classroom, university officials said previous tests for asbestos and lead gave them no reason to believe the building was unsafe. MSU buildings have regular preventative maintenance with checks to HVAC systems, lighting, plumbing, windows, doors and more.

A spokesman for MSU said there was nothing new to report about the health investigation.

One in three people will get cancer in their lifetime.

State toxicologist Richardson said cancer is "unfortunately very common," especially breast and thyroid cancer. When officials are analyzing a building or environment for carcinogens, they're looking for many cases of one specific type of cancer or related cancers in a specific area and during a specific time period.

Age, work history, breathing rates, water intake and chemical exposure are other factors. Someone developing cancer due to environmental exposure depends on how much, how long, how often and at what age they're exposed to a substance.

One example is mesothelioma found in people who work where they're inhaling asbestos particles.

"There's a specific link between that type of cancer and that exposure to asbestos," she said. "That scientific link would be supported by people being exposed to that chemical and that chemical getting into their body. So asbestos in ceiling tiles doesn't necessarily mean that you're being exposed at a level that would be dangerous because it's not necessarily getting into your body."

CDPHE is usually alerted of a suspected cancer cluster by concerned residents, said John Arend, manager of the Colorado Central Cancer Registry.

"We always try to perform an analysis when possible," he said. "Typically we'll work with the individual or local agencies to get information about the area, if there are any known or suspected environmental exposures and what the cancer types of concern are. And then we'll combine that with data from our statewide cancer registry to determine if the number of cases in that area is similar or different to what we would expect."

Correction: A misspelling of Dr. Jon Samet's name has been corrected, as has a mislabeling of the Colorado School of Public Health.