It wasn't supposed to happen, but it did.

An 8-to-4 vote Monday night at Denver City Council denied new contracts for two massive corporations operating "halfway houses," places where former prison inmates can readjust to life in the city.

This sort of decision usually gets a vote without much public discussion, but City Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca secured a public hearing over the contracts with GEO Group and CoreCivic, which also operate private immigration prisons across the country.

The hearing and deliberation lasted for hours as CdeBaca's colleagues wrestled with the moral question of extending a contract with companies that seem to stand against the council's stated values. CoreCivic is at the center of a lawsuit filed after a migrant baby died in its custody. GEO operates an immigration prison in Aurora, where an enormous protest made national news a few weeks ago.

CdeBaca wanted the city to divest from the corporations, whose profits are sometimes used to support political campaigns. And it happened.

Three out of four halfway house residents stay out of jail after completing the program, according to Greg Mauro, director of Denver's Division of Community Corrections, which handles halfway houses in the city.

"It's a risk reduction model," Mauro told City Council members. "We know that by reducing risk we can reduce recidivism."

There's a caveat to that statistic, however: The recidivism rate only accounts for the first year after finishing the program.

Reps from GEO Care, GEO Group's halfway house subsidiary, said in a statement that "politically-motivated" councilors shared "false information" about their parent company. Mayor Michael Hancock's staff also issued prepared remarks, saying the mayor and his staff were "disappointed" the council nixed the contract without an alternative.

On Wednesday, CdeBaca said she was still floored by the vote. She's proud of the outcome and understands the risk. But the city put itself in this position, she said, by letting the contracts expire without investigating alternatives first.

"We have known for many years that this system is in need of a significant transformation, and we had our city show up unprepared," she said. "I fully expect the city to adapt and course-correct."

She hopes that correction involves community-oriented groups.

No one knows exactly what happens next. The future is cloudy for the 500 people serving out sentences in halfway houses and for Denver's re-entry system as a whole.

Some are hopeful that the unexpected disruption could mean big changes for a system they believe is long overdue for an update. But that hope is contrasted with the angst of uncertainty.

Bryan Sederwall, known by everyone simply as "Pastor B," is hoping for the best. He runs the Denver Dream Center and works mostly with residents of CoreCivic's Fox Street facility. The men he works with are worried.

"They are concerned that they're going to be sent back to prison," he said. "It's been a little bit of a panic."

He said sending people back would be a problem, since the state Department of Corrections is "almost at max capacity."

About two-thirds of people living in Denver's 10 halfway houses are on their way out of state prison. The remaining third avoided going to prison after a judge diverted them into halfway houses.

Addressing City Council on Monday night, criminal defense attorney Tristan Gorman said about 100 beds remain available at state prisons, but it's estimated there are as many as 300 people in GEO or CoreCivic facilities could have to return if the halfway houses aren't replaced. She said the Colorado Department of Corrections would likely ask the state to re-open a shuttered prison in Cañon City for more space.

Sederwall wants the city's cash to stay in re-entry programs, even if it helps former inmates adjust to society in other ways. The thought of sending his clients back to prison is not good.

On Father's Day, he officiated a wedding for one of his clients at City of Cuernavaca Park. It took place during a cookout that allowed people in his program to see and bond with their families. Ex-cons and cops lined a makeshift aisle as the sun baked the wedding party.

People in halfway houses don't often get a chance to see their kids, spouses or parents, but they're a lot closer than they are in prison. Events like the barbecue help service providers like Sederwall prepare clients for the day they're released, and those who attended the Father's Day event soaked up every minute with their loved ones.

Sederwall said he's hopeful Denver will redistribute their halfway house quickly so his client's lives won't be uprooted. Though services vary by facility, he's seen a lot of men make huge strides in his program.

The void created by Monday's vote could be an open space for big change if community-based replacements step in to run corrections programs.

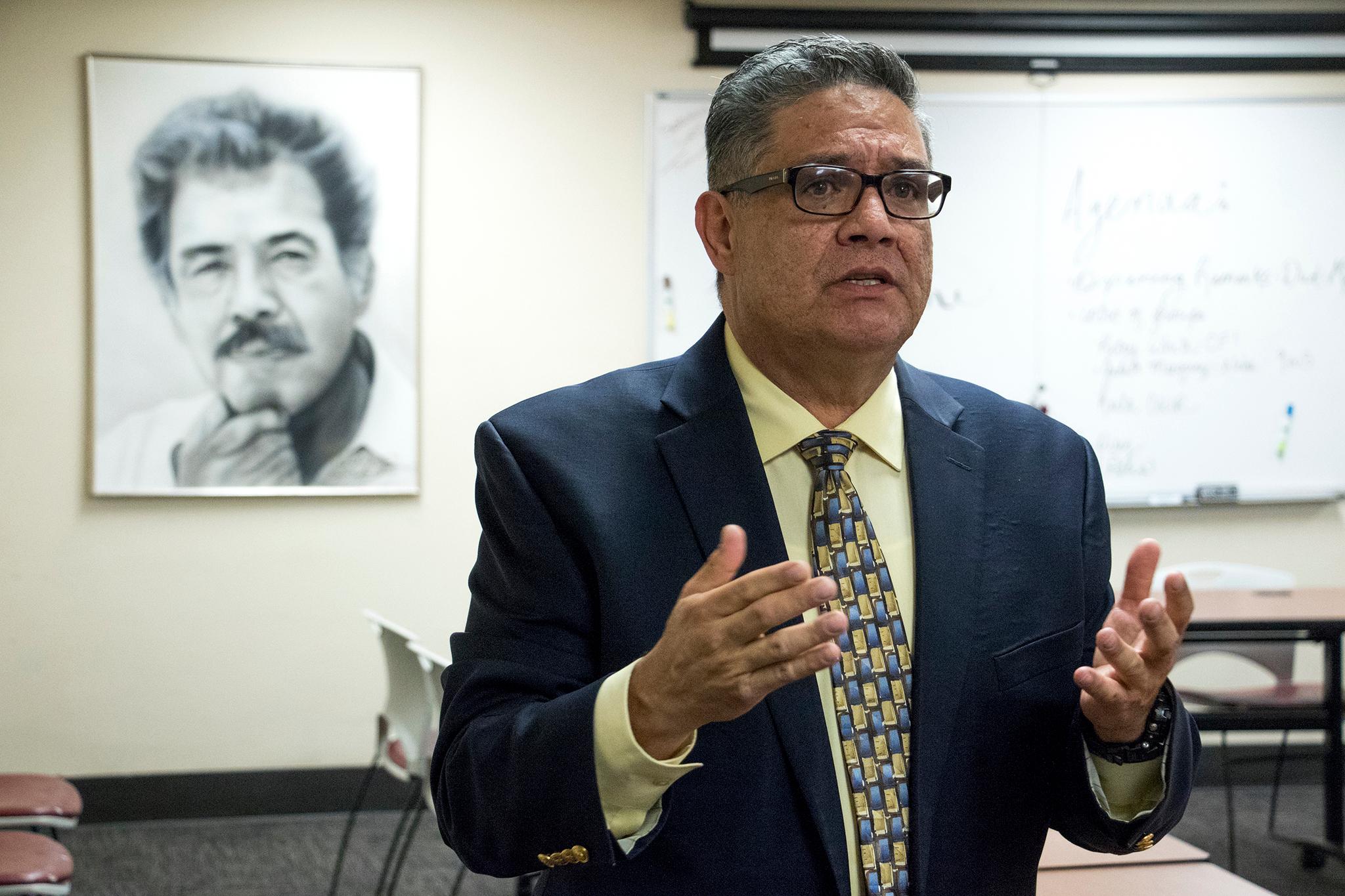

Rudy Gonzales has long been familiar with radical ideas in the face of systemic social problems. A portrait of his father, the controversial Chicano activist Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales, hangs not far from his office inside Servicios de la Raza, the community organization he directs that has handled re-entry funds from the city since 2018.

He, like Sederwall, said there "should have been a solution" in place before the city council approved such a radical move. But while people in his world are "scrambling," he's happy with the sudden change.

"I applaud the decision because there's a line in the sand around that issue," he said, referring to GEO and CoreCivic's involvement with private immigration jails.

"We have historically been against private control of our prisons," Gonzales said. "We're also committed to justice, equity and peace in our communities."

Gonzales has been hard at work with a coalition of local groups to bring novel criminal justice reform to the city, namely civilian responders who would take 911 calls to avoid unnecessary jailing or police brutality. He sees an opportunity for a similar shift now that GEO and CoreCivic are out.

"I hope it opens the door. I hope it creates an opportunity to really implement some significant reforms," he said. "We can really develop more humane and just and equitable solutions."

His conviction is rooted in the success of a state-funded program passed by the legislature in 2015. The Colorado Work and Gain Education & Employment Skills program, known as WAGEES, provides grants to community- and faith-based organizations that operate locally-focused re-entry programs. Last year, an independent evaluation "strongly recommended" reauthorization of the program. Colorado's legislature gave it a five-year extension and tripled its appropriations.

CdeBaca said alternative programs like this should have been considered long before Monday's vote forced the city to act.

Fabian Ortega, Gonzales' deputy director, said GEO and CoreCivic's halfway houses are sometimes "resistant" to work with communities and may force people in their programs to "jump through" unnecessary "hoops."

Elisabeth Epps, a self-proclaimed "abolitionist" who worked with legislators to pass a suite of criminal justice reform measures last session, said private companies "don't have profit motive" to help people in their care stay out of trouble: "They don't make money if people succeed."

Epps, who also worked on CdeBaca's election campaign, said high recidivism shows the old system was not working. Almost 50 percent of prisoners released in Colorado become incarcerated again, compared to 40 percent across the country.

While Sederwall said "there's a lot of value" to Community Corrections, its goal -- to rehabilitate former criminals -- cannot be achieved without third party organizations like his. Without the "wraparound" services he provides, many of the people he works with could end up on the street, back on drugs or back in trouble when they're finished at the halfway house.

"When an ex-offender finally gets released, it's a whirlwind," Serderwall said.

The services they came to rely on inside a halfway house suddenly disappear when they leave, which makes transitioning into Denver's expensive, competitive market a bigger challenge.

"There's no true process and there's just so many hurdles," he said.

In a prepared statement, a spokesperson for CoreCivic said the company has a "longstanding track record of delivering meaningful reentry programs" administered by "nearly 100 reentry professionals with decades of experience."

While the prepared statement from GEO Care said its parent company's immigration jails are "unrelated" to their re-entry work, CdeBaca said she's not so sure.

"One has to ask themselves when and where and how the money from these contracts commingles with the other services that they're providing," she said.

Denver paid out more than $17 million to GEO and $38 million to CoreCivic since 2011. The city's contracts with the companies go back as far as 2001.

But not everyone is so leery. Sederwall said the CoreCivic halfway house he's worked closely with have been great partners. Still, he's not opposed to seeing some change if there's a safe landing ahead.

"I'm OK if you've got to shake things up," he said. "Sometimes if you don't have a big change, you're not going to make big decisions."

That big change wasn't supposed to happen, but those big decisions might.

CPR News reporter Ben Markus and Denverite reporter David Sachs contributed to this report.

This story has been updated.