On Thursday, Mayor Michael Hancock and City Councilwoman Robin Kniech framed their push to raise wages citywide as a means to greater equality in a city with a widening gap of haves and have-nots. But while one restaurant owner lent his support during press conference, the industry as a whole is not on board.

Yesterday Hancock and Kniech announced their plan to gradually raise Denver's minimum wage to $15.87 per hour in 2021, after which the wage would rise with inflation.

The city government can't control the rents or home prices pushing people out of the city, but leaders can flex their muscle when it comes to wages since the state legislature opened the door last session. Of the approximately 105,000 workers who will benefit from the proposed wage hike, nearly two-thirds will be people of color, according to city data. More than half are women.

"So a wage increase is racial justice in action, and it's personal for African Americans and for Latinos who will have a better chance of staying in their community," Kniech said.

Adam Alleman, who owns the Denver Game Lounge restaurant and bar in Hale, said he's all for the "triple bottom line" that accounts for social well-being as well as company profits. The more money people have, the more money they'll have to spend on dining and entertainment, he told Denverite.

But Sonia Riggs, executive director of the Colorado Restaurant Association, says she's worried about the proposed law. Most restaurants already pay cooks and dishwashers $15 an hour, according to Riggs, whose group surveys restaurant owners.

The law will make restaurant owners widen the pay gap between back-of-the-house workers -- cooks and dishwashers -- and servers, she said, leaving less money for rent, food or additional employees.

"It forces them to give a raise to the front-of-the-house employees when they want to give a raise to back-of-the-house employees," Riggs said. "So when this happens they have very few options for how they're going to accommodate that change because they also have a family to feed."

It's not uncommon for servers to make more than restaurant managers because they make so much money in tips, Riggs said. Colorado servers get what's called a "tipped minimum wage" of $8.08, which is lower than the standard minimum wage of $11.10. The proposal doesn't account for tips so the hike is too much, too fast, according to Riggs.

"Name one employer that can absorb that," she said.

In 2018, taxes on restaurants contributed over $128 million to Denver's general fund -- 10 percent of the city's bottom line -- according to the budget office.

Restaurants can always raise menu prices (which comes with its own set of effects). Retailers do not necessarily control the prices of their products. Tattered Cover co-owner Len Vlahos, who sells books, told Denverite he is still digesting the proposal and is not ready to comment.

If City Council passes the bill, Denver would join 13 other cities and counties with a minimum wage at or above $15 by 2021. It would be the ninth city to adjust wages based on inflation.

The $15 minimum wage movement has been going on for years. But $15 in 2015 is worth about $13.76 in 2019 dollars when you account for inflation. So why aren't Hancock and Kniech starting at a higher base? Turns out they're moving as fast and going as high as the state law allows -- a 15 percent annual increase, according to state law.

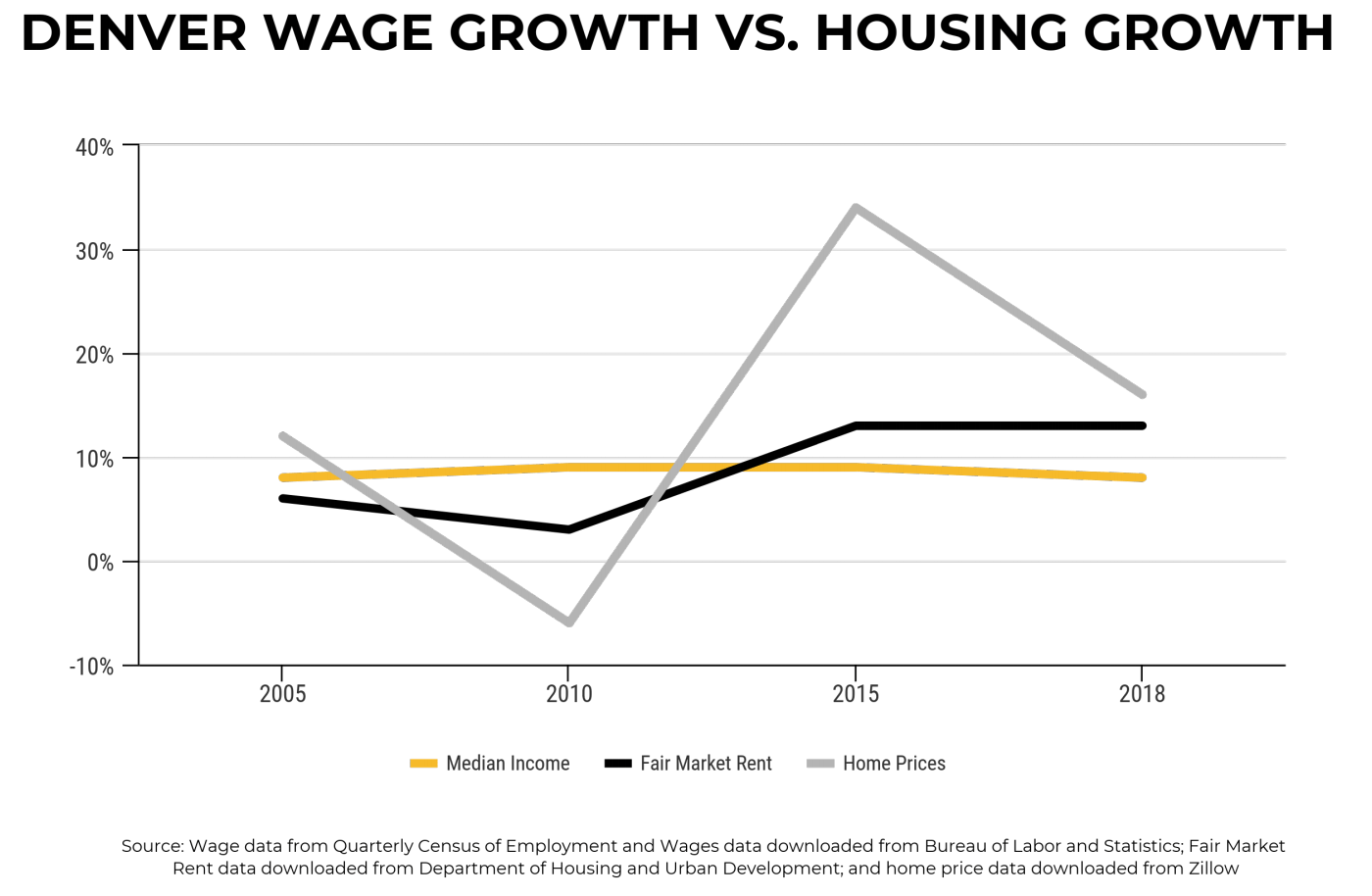

"For decades, wages and incomes have been falling behind other rising costs," Hancock said. "That means more and more families haven't been able to keep up."

The next step, according to Kniech, is to engage "stakeholders" (what government types call the people who will be affected). Kniech said she and the Hancock administration have had conversations with private industry reps, but not in an official capacity. Meetings with business owners, lobbyists and the general public will begin in October with a goal of implementing the law Jan. 1.

The restaurant industry's Riggs plans to attend. But she said the process should have included her group from the beginning. She hopes Hancock and Kniech will agree to implement pay raises more gradually.