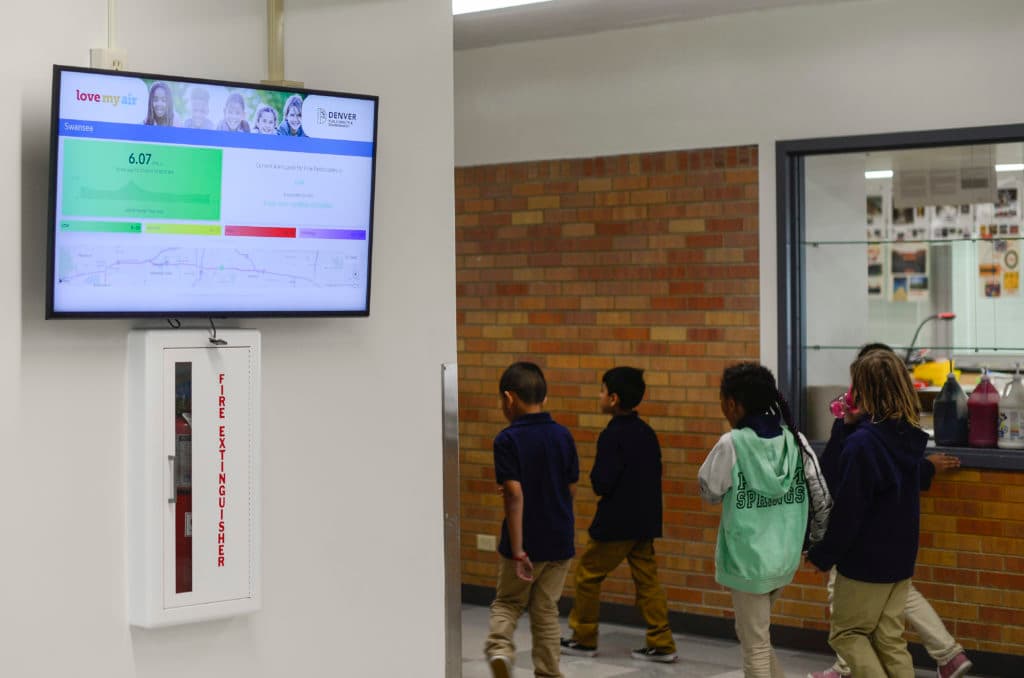

Thursday morning students at Swansea Elementary School made their way to recess by passing under a newly installed television screen in the hallway. As the children walked by, the screen illuminated a green graph with the number 4.9 and the suggestion: "enjoy your outdoor activities."

Installed in August, the screen, which is connected to an air monitor, is part of a pilot program to display real-time air-quality data from outside nine Denver schools. Parents and the general public can also check the air quality online.

The screens break down data on a simple four-tier scale: green for good air quality, yellow for medium, red for poor and purple for very poor. For now, the data is simply informational, but eventually it will be used in coordination with health data to create programs aimed at reducing youth asthma levels.

"Asthma is one of the top reasons that kids miss school," said Christy Haas-Howard, an asthma specialist and a nurse with Denver Public Schools. "So this is about educating and empowering school communities."

The pilot is the first phase in the Love My Air Denver program, a partnership between the Denver Department of Public Health & Environment and Denver Public Schools. It launched last year with $1 million from Bloomberg Philanthropies. In addition to the nine monitoring stations, the grant will help deploy air quality monitors at 10 more schools before the end of the year and a total of 40 by 2021.

Along with compiling the air quality data, schools are also collecting health data from students, which will be analyzed through a partnership with the University of Colorado.

The focus of the air-quality data collection revolves around tracking PM2.5, the scientific term for tiny shards of particulate matter. These particles -- about 3 percent of the width of a human hair -- can penetrate deep into the lungs and eventually work their way into the bloodstream. Particulate matter can be dangerous for anyone, but children are particularly susceptible because they tend to spend more time outside and are generally more active and smaller than adults.

Swansea Elementary, Garden Place Academy, Sabin World School, Gust Elementary, South High, Bruce Randolph School, Northeast Early College, PREP Academy and University Prep-Steele Street all have air quality monitors.

They were chosen based on their asthma rates, the percentage of students who qualify for free- and reduced-price lunches and the school's readiness to implement a program.Most of the schools that met this criteria are in low-income areas, and historically the city government and residents of these neighborhoods have had a strained relationship over air quality issues.

The city government held workshops on air quality issues for parents at the schools as well as several focus groups to collaborate on how the data would be presented on the screens in the school and online. For Marisol Veana, the parent of two children at Swansea Elementary, the process helped her feel more informed about the effects from the I-70 construction next to the school.

"As a mother, I took up the responsibility of educating myself," Veana said in Spanish. "More than anything, I wanted the information to be available to help all the families in the area have a better understanding of what is happening."

Until recently, the air quality monitors used in this program were too expensive for such a wide study, and the full effects of pollution on asthma and general health are not fully understood. The project's leaders hope that the data will eventually help pinpoint the causes of elevated asthma rates, and in the meantime that the pollution information will be available to concerned locals.

Within the schools, project organizers hope they can reduce the exacerbation of asthma symptoms in students who already have it -- reducing the number of days students miss school due to asthma or the number of times they need to visit the nurse because of their symptoms. In the long term, the goal is to reduce asthma rates overall.