It could have been her former self she was hearing.

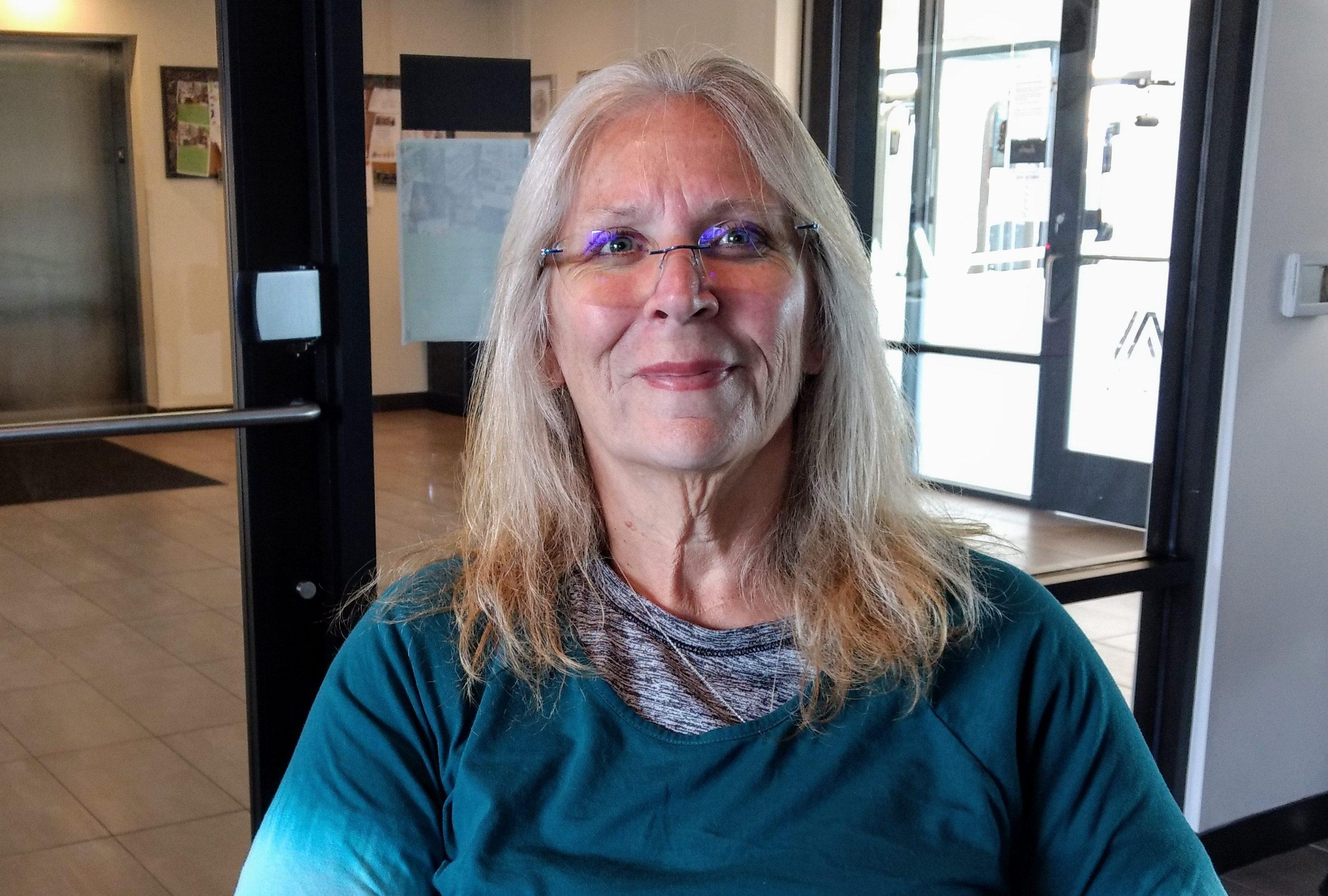

Pam Gantenbein was listening to her Westminster neighbors urge their city council to vote against a proposal for a below-market-rate housing complex. When she owned her own home, she thought, "I don't want affordable housing in my backyard. It's going to bring crime. It's going to bring down my property values," she said in an interview.

After suffering health setbacks and leaving her marriage and her house, Gantenbein struggled to find a place of her own that she could afford. She eventually moved into an apartment in ALTO, a Westminster building developed by Unison Housing Partners, once known as the Adams County Housing Authority, where rents are kept within reach of households earning no more than 60 percent of the area median income.

Gantenbein had little patience for concerns being expressed at that September council meeting about whether the new housing would create traffic or have enough parking.

"Parking spaces?" Gantenbein said when her turn came at the microphone during the public comment period before council members voted. "I couldn't find a place to live. And we're talking about parking spaces? I was going to live in my car. Do you know how scary that is? You know how much I wanted to not live because of that?"

Gantenbein was among 50 people who had signed up to speak, so many that the meeting lasted until almost midnight and was adjourned and resumed the next night. In the end, the vote was 5 to 2 in favor of the zoning changes needed to proceed with plans by Denver's St. Charles Town Company to develop 216 apartments at the corner of Federal Boulevard and 97th Avenue. The complex, called St. Mark Village, will have one, two and three bedroom units attainable for households earning between 30 and 60 percent of the area median income -- between about $25,000 and $50,000 for a family of three.

A 2017 study commissioned by the city found that more than 4,000 people were on waitlists for the 800 rent-restricted rentals in Westminster. In an interview following the St. Mark Village vote, Mayor Herb Atchison said his city was committed to addressing the crisis those numbers represent as housing prices rise faster than incomes.

"The need is not only in Westminster. It's throughout the area," the mayor said. "And it's not just the metro area. It's statewide."

Atchison, who voted for St. Mark Village, said that city officials listen to everyone who comes forward to testify, but that he based his vote on something else:

"I saw the need for the housing."

Councilwoman Anita Seitz, who also voted in favor of the development, said afterward in an interview: "When people are willing to share what's obviously been a difficult journey for them ... I think it's very courageous."

Seitz said she considered recommendations from city staff in favor of the development and weighed testimony on both sides.

Weeks later, even the two council members who opposed the development had vivid memories of several residents of ALTO who came to lobby for affordable housing.

"I think it was very powerful to hear them," Councilman David DeMott said. "I think it speaks to the need for people to have places to live."

DeMott said he took into account concerns of people who already have homes in the neighborhood about the impact St. Mark Village would have on their quality of life. He also thought potential newcomers would be living in crowded conditions.

The neighborhood now is composed largely of low-rise single-family homes. St. Mark Village will have seven three-story buildings on a six-acre lot. Jon Voelz, who joined DeMott in opposing the development, said he was moved by the ALTO residents' testimony and believes "public housing in that area makes sense. Just not at that density."

Gantenbein is philosophical.

"Some people's attitudes will change when they become informed," she said. "Others' won't."

She said she was excited when she saw the vote go St. Mark's way. Just taking action was also a victory for her.

"It's good to be needed," she said. "It's good to have a purpose. It's good to see that your voice counts."

"I just want to know how we can make it easier" for people on low incomes to find housing they can afford, she said, saying she hoped telling her story would help.

"There has to be more of it (affordable housing) being done," she said.

Gantenbein didn't set out to be a housing activist when she moved to ALTO.

Her journey to the city council meeting started with being asked to sit on the hiring committee for a new staff position for Unison: community organizer. It sounds like a political agitator. But Linnea Bjorkman, who got the job with Gantenbein's support, described it more as an apartment manager with a social conscience. Bjorkman started last November. Her initial duties included organizing a community council, on which Gantenbein sits, to help residents bring concerns to management.

The council, which has a core group of about a dozen, lobbied for things like a barbecue grill and shade structures in the 70-unit complex's outdoor common areas. The council helped get a mini free library started and it's working on a food pantry.

"We are hoping to be able to say in affordable housing communities that these strategies tend to work to build community ... to activate the voices of community on issues that concern them," Bjorkman said.

Bjorkman heard members of ALTO's community council express interest in and curiosity about affordable housing. That led to workshops on topics like Section 8, the federal program to help low-income households pay rent, and low-income housing tax credits.

Developers make proposals to the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority for the tax credits, which are awarded on a competitive basis. Developers who get credits sell them to investors for cash they can use to build, allowing them to borrow less. Because their loan costs are lower, they can charge less rent once their housing is built.

Gantenbein and another ALTO resident, Mike Medina, became so interested that Unison sent them to the annual conference hosted by Housing Colorado, a nonprofit that lobbies for affordable housing solutions.

It was at last year's conference where Gantenbein for the first time heard about issues like redlining, the historic practice of designating neighborhoods that were predominately minority or immigrant as risky places to make home loans. Research shows that because of the resulting lack of private and public investment, the redlined neighborhoods of the past became today's areas of low incomes and savings and high poverty and unemployment.

Gantenbein said she "got fired up about the wealth gap and redlining."

"I was just, really, naive about stuff like affordable housing, Medicaid," Gantenbein said, referring to the government program to help low-income people pay for healthcare. "I worked hard all my life. I owned a home. I never thought I would need affordable housing or be on Medicaid."

Gantenbein is a former powerlifter who was paralyzed from the neck down in a training accident 15 years ago. The injury did not at first stop her from working as an optician. A few years ago she ended up with a broken leg that led to hospitalization and rehab. She had been thinking even before her medical crisis that she wanted to end her abusive marriage. When she left rehab, all she could afford was renting a room from her sister.

"I thought I was going to have to live in my van," she said. "I hated the room I was living in."

She thought she had found a place in an affordable housing project for seniors, only to learn the minimum age had been changed to 55. Gantenbein, now 59, was 54 at the time.

"I was just heartbroken," she said. "I just wanted to go sit in front of a bus."

She heard ALTO was being planned and one day saw a banner advertising the project. She emailed a contact on the banner. The building opened a year later, last spring. Gantenbein was the first to move in.

"I got blessed to be able to live here," she said in an interview in the community room at ALTO, her black high-top sneakers set on the footrests of her wheelchair.

Her subsequent education in affordable housing included more workshops. At one, she and her neighbors met representatives from St. Charles Town Company, the Denver developers planning St. Mark Village.

In August the St. Mark proposal had squeaked through the Westminster Planning Commission 4 to 3. St. Charles had heard vehement opposition at neighborhood meetings.

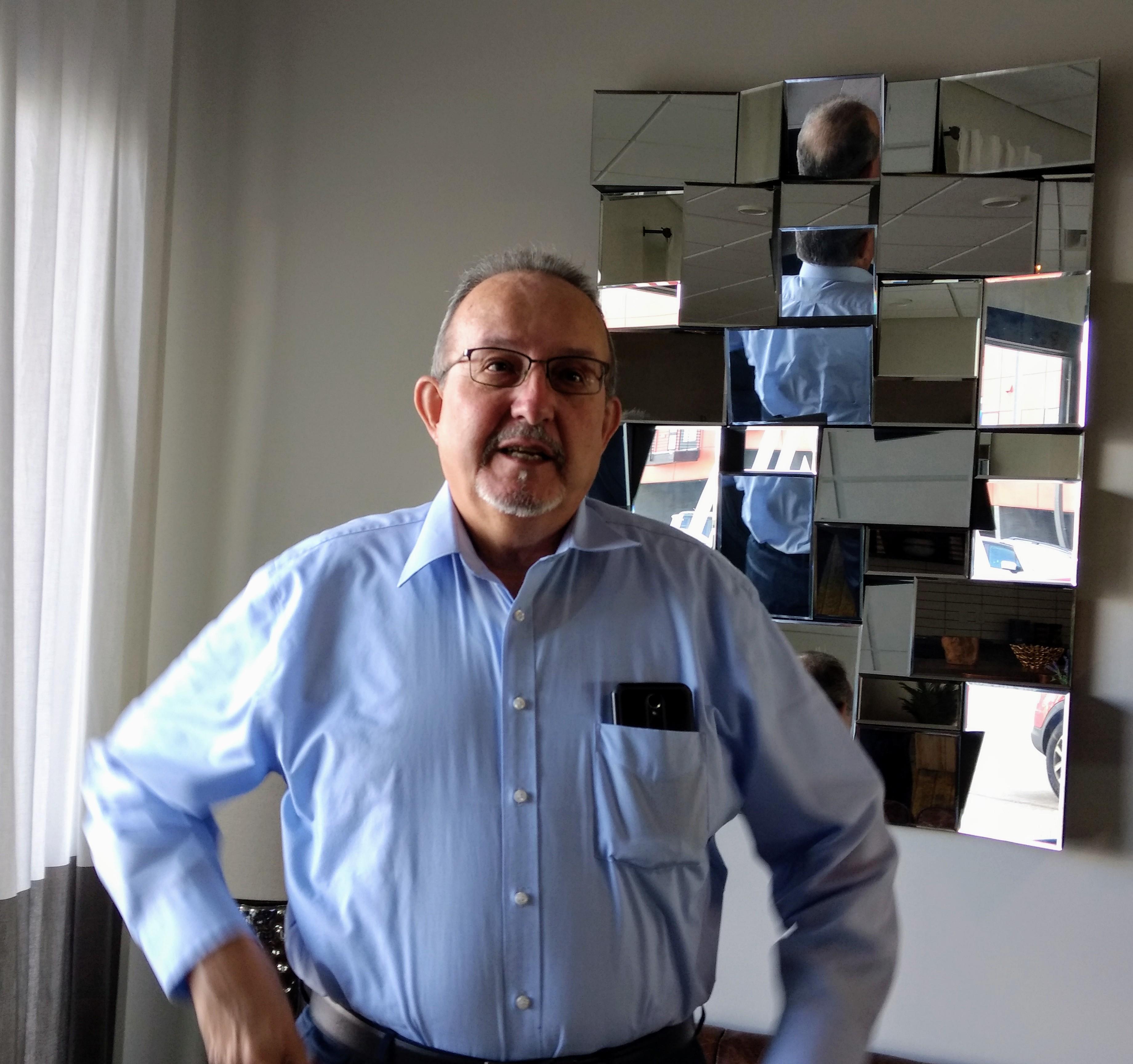

"We had people stand up in previous meetings and say, 'We don't want these people here. It's going to be crime-ridden,'" said Charles Woolley, who founded St. Charles in 1993 and is the company's president.

For the city council meeting, "we reached out to everybody we thought could speak in favor of the project."

St. Charles has built market-rate commercial and residential properties. In 2005 it completed its first affordable project, Brunetti Lofts in Denver's Ballpark neighborhood. It has developed several others since.

"The demand is so strong for affordable housing in this community," Woolley said. "It has been for the last decade. "You could build an affordable project almost anywhere and it would fill up overnight because there are so many families in need."

The National Low Income Housing Coalition reported in its latest annual analysis that metro Denver had just 26 affordable and available rental homes for every 100 families who were either below the poverty level or earning less than 30 percent of the area median income. The coalition uses a common computation to determine affordability: rent should not take up more than 30 percent of a household's income. The coalition also looked at how many units were actually available -- not rented to higher-earning households -- to the poorest households.

At ribbon-cuttings for his affordable projects, Woolley has heard residents talk about how their lives were transformed by having stable housing. He'd never asked anyone to talk about needing affordable housing at a city council meeting, he said.

"We never needed to. It's very private," he said.

But he said he'd never before met the kind of opposition St. Mark Village sparked in Westminster.

Woolley he thought his proposal would be defeated at one point.

"I do think the stories had impact," he said of the testimony from ALTO residents. "We were having a battle and they were there to help."

Medina, the ALTO resident who had gone to the housing conference with Gantenbein, had spoken at the state legislature earlier in the year in favor of a proposal to double the annual the cap, from $5 million to $10 million, that the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority can distribute in low-income housing tax credits. That bill became law.

Medina is a former alcohol and drug addiction counselor who lost his home after a back injury forced him to quick working. Like Gantenbein, he was once an affordable housing skeptic.

"I was of the mindset where I thought that everybody, well, I shouldn't say everybody, but a good many folks that resided in affordable housing were folks who were lazy, not willing to work, and looking for the easy way out," Medina said during the council meeting.

He went on to describe his embarrassment at having his house foreclosed on and having to move in with his daughter and son-in-law for a year before finding a home he could afford at ALTO.

"It's really hard to find an affordable place to live," Medina said.

Medina, who debated in high school and college, had been just as revealing about his own situation in his remarks at the state legislature. He was a more practiced public speaker than Gantenbein.

"I hadn't seen a town council meeting in some time," she said.

Both responded to the call for help from the St. Mark Village developers. Gantenbein said she thought the city council just needed to see the faces of people who needed a place to live. She prepared and practiced a speech, but at the microphone felt moved to respond to opponents' concerns over parking. She spoke haltingly at first, then gained strength before she summed up:

"If we don't have housing, our souls die. Our community dies. Please, vote this in. That's all I have to say. Thank you."