The work of Denver muralist Allen True graces the Hoover Dam, state capitols in Colorado, Wyoming and Missouri, even Wyoming license plates.

Some of his art was destroyed along with the buildings that hosted it, or was banished to storage.

One piece, after more than a decade out of sight, can be seen again in a historic Denver building that has been converted into apartments for seniors on low incomes.

Celebrations earlier this month of the completion of Tammen Hall also marked the resurrection of the mural that True completed in 1932 for the former nurse's residence, built in 1930. Tammen Hall now houses 49 apartments for people 62 or older. Rents are kept to no more than a third of tenants' incomes and only seniors earning up to 60 percent of the area median income can be residents.

True's lush, five-panel mural depicting Native American men and women in everyday settings is just one of the painstakingly restored architectural and design elements surrounding residents who might have been priced out of the gentrifying neighborhood. Annie Robb Levinsky, executive director of Historic Denver, called the project proof that history and affordability can coincide. Tammen benefitted from both historic and low-income housing tax credits.

"It's a great example of how those programs can be teamed up to meet community needs," said Levinsky, whose nonprofit works to preserve historic sites.

The housing would not have happened had the developers not been awarded state and federal historic tax credits, said Kurt Frantz, development manager for MGL Partners. Developers sell credits to investors for cash they can use to build, allowing them to borrow less. Because their loan costs are lower, they can charge less rent once their housing is built.

"The project would not have worked with just low-income tax credits," said Frantz, whose MGL worked with Solvera Advisors to develop Tammen.

Frantz said renovating a historic building is more costly than erecting something new.

"That's why they have the historic tax credit. It closes the gap," he said.

Pairing historic credits with low-income housing credits "does definitely work for affordable housing," he said. "It's a good combination."

Frantz said he would recommend other affordable housing developers try it -- but said Denver no longer has many historic buildings that haven't already been redeveloped.

"If you see one, grab it," he said.

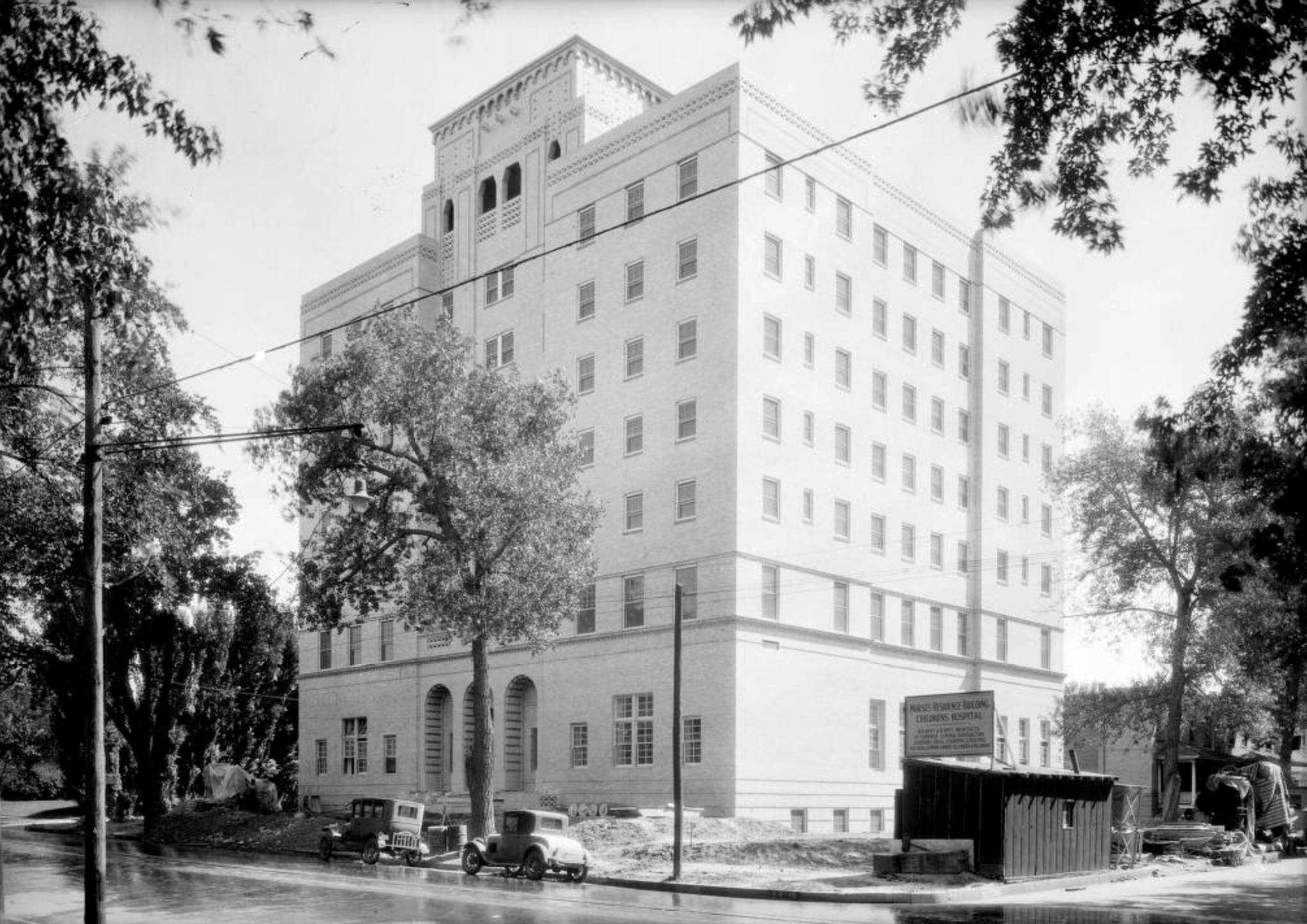

Tammen Hall, originally part of Children's Hospital Colorado, was declared a Denver landmark in 2005, two years before Children's moved to new quarters on Aurora's Anschutz medical campus. Tammen, which had housed nurses and later offices, sat empty after Children's left, even following the campus's purchase by Saint Joseph in 2009.

Heidi Huisjen, arts coordinator and curator at Children's Hospital Colorado, said a predecessor ensured the True was not abandoned.

"She saw to it that Children's hired a conservator," Huisjen said.

Huisjen called Carmen Bria, chief conservator at the Western Center for the Conservation of Fine Art, the "True mural art angel."

"There was a lot of tender loving care," she said, saying that when the panels were pealed off Tammen walls, some paint separated from the canvas.

In addition to conserving the mural, the Western Center for the Conservation of Fine Art stored it during years of questions about its fate.

Huisjen called the mural "an unusual aspect" of her hospital's art collection of more than 1,000 pieces. The mural did not fit the modern feel of Children's new Anschutz campus. And Saint Joseph did not have a use for Tammen.

The mural had its fans among Children's staff, some of whom lived near Tammen, Huisjen said. She's among them, pointing out "the elegance of the palette that he (True) used" during a recent visit to Tammen. Levinsky, of Historic Denver, also credited neighbors with keeping a conversation about the mural alive.

"It was a community effort to ensure the murals had a good placement," Huisjen said.

Saint Joseph Hospital sold Tammen to MGL and Solvera Advisors in 2017. Not long after the sale, designer Michelle Forrest, whose The Neenan Company was brought in as the design-build partner for Tammen Hall, heard from Children's. The hospital wanted to return the mural to Tammen on permanent loan.

The mural had originally been installed in Tammen's second-floor library. When Huisjen reached out, Neenan had already determined the library would be converted into apartments. Forrest saw a fitting new setting in a ground-floor space that had been a community room for the nurses and would serve the same purpose for the seniors.

The community room has an original ceiling that looks like terra cotta tiles, but which Forrest said was one large section of apparently hand-painted quartzite material.

"There's a lot of care and effort put into the ceiling," Forrest said. "The space is so grand."

She placed the five sections of the mural in new paneling over an original marble fireplace -- no fires can be lit in it now, to protect the mural from heat. The warm yellows, greens and reds of the fireplace and the ceiling complement True's colors. Bria, the Western Center for the Conservation of Fine Art conservator, mounted the canvas sections on a pliable material that floats just off the wall, secured in Forrest's moldings. If the panels ever have to be moved again, they won't be damaged as they are taken down.

"They were super mindful of details," said Huisjen, the Children's curator.

Forrest said sometimes spending a bit more time and money to get those details right pays off in a building that will make people feel welcome. She said renovating any older building involves expenses. The advantage of renovating one that has been declared historic, she said, is the possibility of getting historic tax credits to offset costs.

With Tammen, Forrest said, the result of her team's efforts was turning a building that had served people by housing nurses into one that continues to serve people: seniors who need homes.

"That's what made this project exciting," she said. "It was not just the preservation of a building. It was the preservation of a community."

The community room can be reserved for use by people who do not live at Tammen.

"I am just delighted that the murals are back and they are being shared with the community," Huisjen said. "I'm never going to get tired of them, of having conversations about them. It was my favorite project."

At Children's, Huisjen's job is both custodian of art and promoter of art's healing powers. She brings in artists to work with patients and considers how the placement of paintings and sculpture can encourage important conversations among staff, patients and patients' families. She sees something nourishing in True's depictions of Native American men and women caring for animals and children amid flowers and birds.

True, who died in 1955, was known for his Western scenes and his deep study of Native American culture. He explored frontier themes in his statehouse murals and used Native American motifs in the hallway floors inside the Hoover dam. In 1935 a True drawing of a bucking-horse-and-rider became the Wyoming state license plate logo.

True was already established as a magazine and book illustrator and was making his name as a muralist when he got the Tammen commission. True, an 1899 graduate of Manual High School who studied at the University of Denver and the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design in Washington, D.C., also created work for Denver schools, library branches and businesses.

In addition to creating a setting for True's mural, the design team Forrest led for Tammen's renovation preserved and complemented period details throughout the building. In a theater the nurses used across the lobby from the community room, Forrest used steel and drywall to mimic traditional plasterwork. Metal screens with intricate art deco floral patterns cover the radiators. A basketball court on the ground floor has been sectioned off into residents' storage spaces, but a basket still hovers overhead. The slots have been blocked in a mail chute reaching from the eighth floor, but the brass mailbox in the lobby gleams. As do the terrazzo floors.

"You could never get terrazzo floors today in your affordable property," Historic Denver's Levinsky said.

"With character comes really solid construction," she added.

"We have seen it as a trend in recent years," Levinsky said, pointing to other examples of historic and low-income tax credits being used to create affordable housing. Among them is the First Avenue Hotel at 101 Broadway, whose developer is using historic preservation credits and other tools. A project to turn a circa 1927 Temple Buell-designed school in the Denver suburb of Wheat Ridge into 16 apartments -- five set aside for households earning no more than 60 percent of the area median income -- relied on historic tax credits and other financing.

Neenan, the design-build partner for Tammen Hall, had a role in the recent renovation of Leadville's Tabor Grand Hotel Apartments, 37 affordable units in a building originally built as a hotel in 1885.

"That took a lot of conversation and review with our historic partners," Forrest said. "It just takes a lot of care."

An affordable project requires many partners, each with their own regulations and goals. SCL Health, Saint Joseph's parent company, pitched in funding to turn Tammen Hall into affordable housing, as did Denver Economic Development & Opportunity. Other players include the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority, which awards tax credits, and Denver Housing Authority.

"We're very collaborative at Neenan," Forrest said, adding she's worked on market-rate projects involving even more partners than did Tammen.

Forrest takes satisfaction in affordable projects.

"It's an important need," she said.