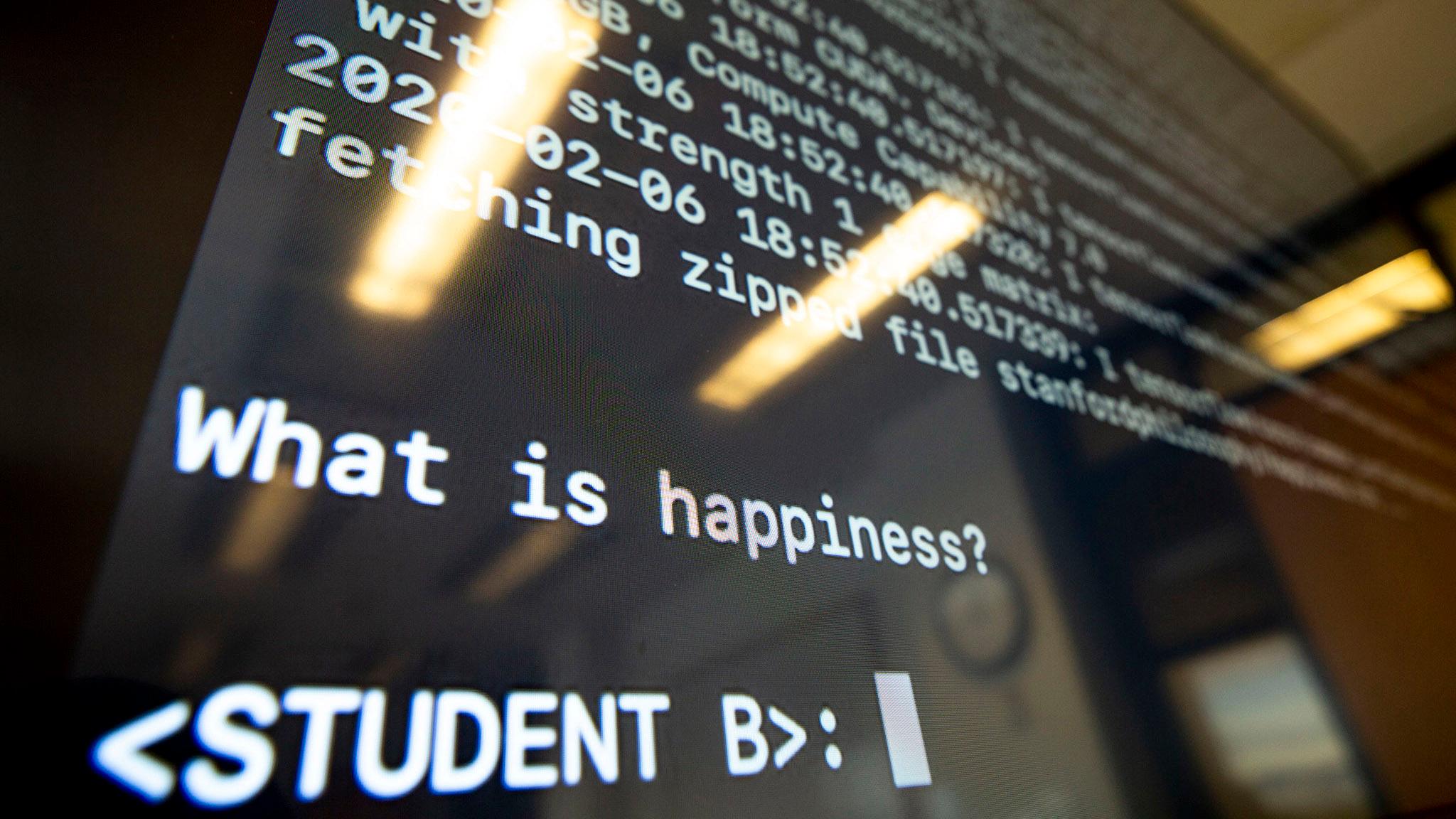

Three researchers sit around a table and peer up at a screen. White letters dance across the display, and then a command prompt appears. Their artificial intelligence program is ready to speak with them.

They begin with a question to start the conversation: “What is happiness?”

Data scientist Justin Barber shifts his gaze from the screen to a laptop, which is running the program. He types in an answer: “Happiness is a state of balance.”

Then he instructs the bot to weigh in. Two new paragraphs light up on the screen.

“Happiness is a state of mind. It is a mental experience of satisfaction with the good or the bad things in one’s life,” it reads. “Theories also focus on the positive impact that one’s life makes on the life of one’s spouse and on the positive impact that the spouse’s life makes on the life of the couple as a whole.”

“Weird,” says Michael Hemenway, co-director of the Iliff School of Theology’s AI Institute.

Weird is one way to put it. Hemenway wants to know: Why is this bot talking about spouses? But then again, why talk to a bot about the meaning of happiness in the first place? And, further, why is a century-old theology school even studying artificial intelligence?

Hemenway, Barber and their colleague, Professor Ted Vial are leading the endeavor in a broader plan to create “the new Iliff.” Their AI Institute and a new Center for Eco-Justice were created so the school could tackle large, global issues through an ethical lens. It’s an initiative to ensure Iliff remains relevant as the world changes around it.

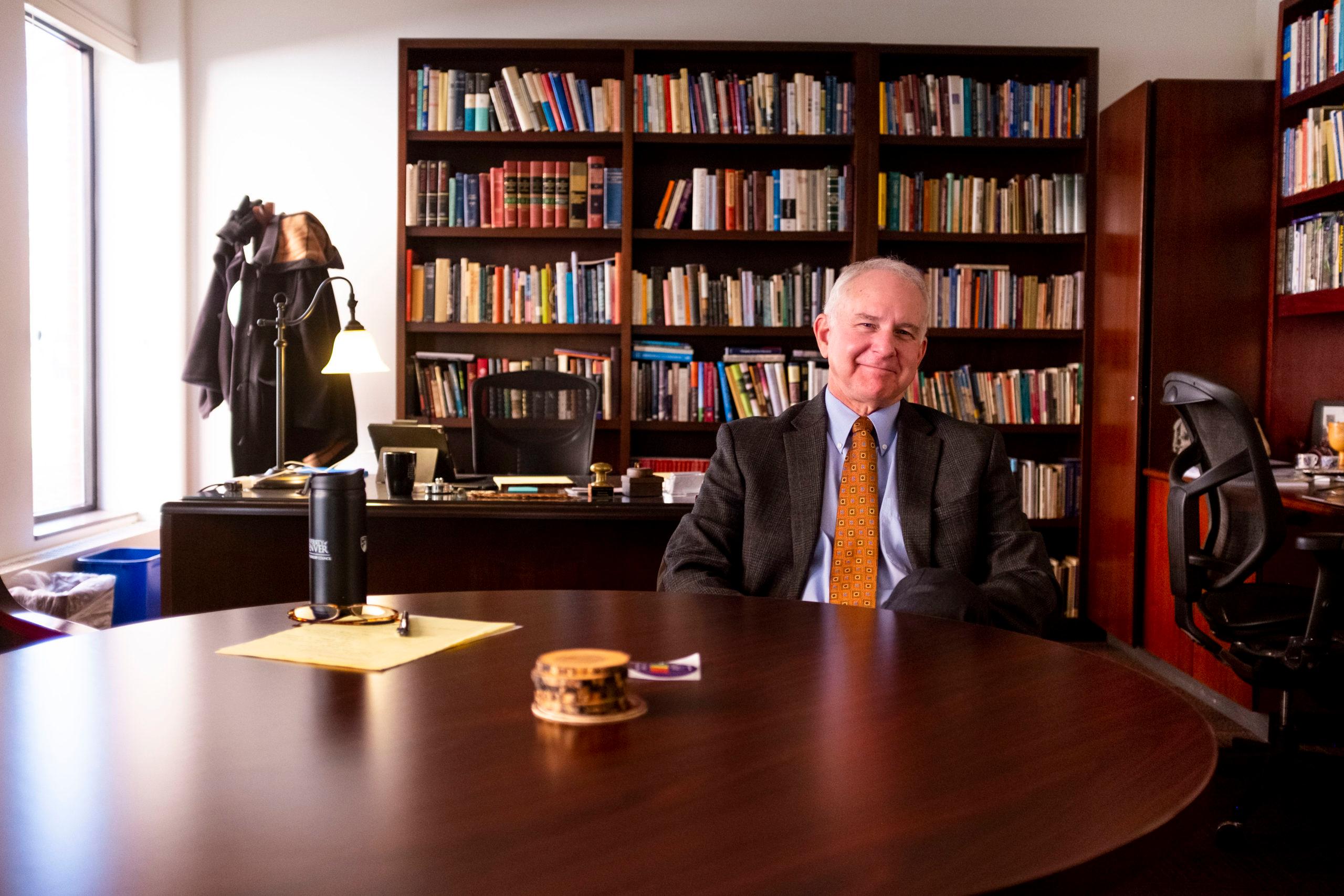

Tom Wolfe, Iliff’s president and CEO, said the writing has been on the wall for a long time.

Nationwide, undergraduate enrollment in American colleges and universities has declined through the last decade. More worrying to his Wolfe, whose institution specializes in religion, is a trend of secularization that social scientists have measured since the 1960s. It means fewer people may be interested in the kinds of religious studies that once defined the school, he said.

But Wolfe said an education at Iliff in 2020 is now geared less toward training in a specific denomination. Yes, many of their students may go on to lead congregations when they graduate, but he hopes the school becomes known for teaching ethics, social justice and a commitment to a “moral discourse.” These are things he said people still hunger for, even if they don’t fit with every interpretation of traditional religious beliefs.

“What we are doing at Iliff is we are recognizing we are in this cultural shift,” Wolfe said. But he wanted to be clear: “We are not in survival mode. We are in a transformational mode so that we align ourselves and what we have to offer the world in a much more meaningful way.”

OK, back to this robot and the meaning of happiness.

Barber, Hemenway and Vial have a few goals for the bot they’ve been tinkering with over the last year.

In the immediate future, they want to develop something that can participate with students during discussions in online chatrooms. Many of Iliff’s students are enrolled in online courses, so a lot of their deep discourse already happens in these spaces. The idea is to bring a new “voice” into conversations about abstract topics.

Hemenway stressed that they don’t want to fool anyone into thinking the bot is human. The team sees this bot as a “learning partner” — neither peer nor professor — that might lead students toward ideas they hadn’t considered.

The AI program has been “trained” on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. It has a lot to draw from, but the team still has some bugs to work out.

Some of these bugs are just related to how it “speaks.”

The team asked if wealth and happiness are the same thing, but the program got caught in a loop when it answered: “As the philosophers of the East and the West, the Buddhist and the Hindus and the Confucians and the Buddhists and Hindus say, is it that which is a state that is not a state, that is a state and that is not a state that is a state and is not a state and is not a state…”

“Clearly we need some work there,” Hemenway said.

Those gaffs can be comical, but the statement about spouses that Hemenway reacted to demonstrates a bigger problem their institute hopes to address.

“Like, why does the spouse come in here?” Hemenway wondered aloud. “Oh, this is a little bit biased toward traditional couples, right? So if I were a single person here, I’d be like: ‘What the hell?’”

AI systems have come under fire in recent years after human biases were found to underpin their operations. In 2018, for instance, Amazon scrapped a hiring algorithm when the company realized it was eliminating women from its pool.

Iliff’s AI team is working to neutralize negative bias in their learning partner, but they’re actually more interested in the process that they’re building to address these issues. Their solution is less about code and more about transparent tinkering with the bot. Hemenway said open discussion about how AIs are built will become more important as the technology proliferates.

“The institute, as a whole, has a larger goal of trying to help build a trust-based ecosystem in the AI space,” he said. “It’s a much broader approach that has to go on in order to address these systems. It’s not just a technical solution.”

So, every few weeks, Hemenway, Barber and Vial convene with a group to discuss their progress. The team includes an Iliff student, a social worker, an ethics trainer and a technology specialist who wants to see AI aid astronauts during long spaceflights.

The team also includes Philip Butler, a scholar from Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles who is working on an AI module that is “unapologetically Black in all its multiple perspectives,” Butler tweeted.

The steering committee will direct how the bot is tweaked over time. The process is a prototype for the kind of “trust-based ecosystem” Hemenway and his colleagues hope become a requirement behind the scenes for AI development around the world.

It’s a non-technical solution to a technical problem, and it’s why a theological school may be well suited to take on artificial intelligence.

“Iliff has this historic commitment to social justice, and this is an important space in our current world,” Professor Vial said. “We feel like we can bring those values and make a contribution to the development of AI in general.”

Iliff is diving into environmental issues for those same reasons. This year, its Center for Environmental Justice — the other half of what the new Iliff — will send students to Guatemala to research how climate change intersects with an out-migration crisis that has spilled north into Mexico and the U.S. border.

Miguel De La Torre, Professor of Social Ethics and Latinx Studies who runs the center, said he wants to make sure broader conversations on the topic don’t lose sight of the people it affects.

“We’re trying to bring a perspective to the overall discussion,” he said, “and begin to look at how the issues that everyone is talking about directly impacts disenfranchised and marginalized communities.”

Last year, the environmental school hosted a conference on the Flint, Michigan water crisis that put social injustices at its core.

The glitches that make the AI team’s bot say wonky things is a short term problem, Barber said, but ensuring that our systems aren’t racist, aren’t sexist and don’t exacerbate gaps in access will always be a challenge.

“The ethical issue will be a forever problem. I think it is about more about trusting groups,” he said, “and not so much about building technologies that we can trust.”

And while their bot is still in its early stages, it’s already helped these scholars think in new ways.

Asking the bot one more question, Barber typed: “Does my happiness matter?”

“There might be a case for overrating happiness. Some may be more satisfied with happiness in their lives or even if their happiness is not so good,” the bot printed in reply. “The happiness of a person is the sum total of his or her life satisfaction. It is a life satisfaction score that can be computed by adding together his or her life satisfaction at each age.”

“This is beautiful,” Barber said to his colleagues. “I feel like, in some ways, this is coming directly from a machine’s point of view.”

Beautiful and, yes, a little weird.

Correction: The Center for Eco-Justice was originally, incorrectly, named the Center for Environmental Justice.