With a hot pizza in tow, Julian Rai drove right by the spot where state health workers opened COVID-19 testing last week. It was a Friday evening in Lowry, and he was on his way to a hungry customer who lived just across the street.

Rai is something of a gig-economy guru in the city. Besides this job for Grubhub, he regularly earns money delivering for DoorDash, Instacart, Postmates and Amazon Flex and by charging scooters for three of the city's providers. He also drives for Lyft, and he runs a Facebook page for drivers in the area where he moderates discussions about how to make more cash and navigate the industry's changing landscape.

That landscape has shifted significantly in the last week as schools and public venues closed and the reality set in that the coronavirus pandemic had arrived in Colorado. In Rai's Lyft driver group, people have complained Denver became a "ghost town" as customers began to stay inside.

But opportunities to deliver food have abounded.

"Orders are definitely up," Rai said. "I'm not getting any time to stop at all, at this point."

He estimated food delivery requests are as much as double the normal volume. And he's noticed his customers have used his services because they're either sick or afraid to get sick. Some have sent him messages that they may be contagious and asked him to leave their meals on the ground by their doors. One guy said he was diagnosed with COVID-19 and was quarantined at home.

"We didn't have any contact, but I saw him through the window. He's just sitting there watching TV," Rai recalled.

This is a good moment to be in the delivery business, he said.

On the other hand, it's probably a bad time to be a waiter

When Rai grabbed that pizza from a restaurant off Colorado Boulevard last week, there was not one customer sitting inside. Another delivery driver did pop in before Rai got what he needed and headed out the door.

"We're picking up constantly from empty places," he said. "The servers are upst ebecause they're not making money."

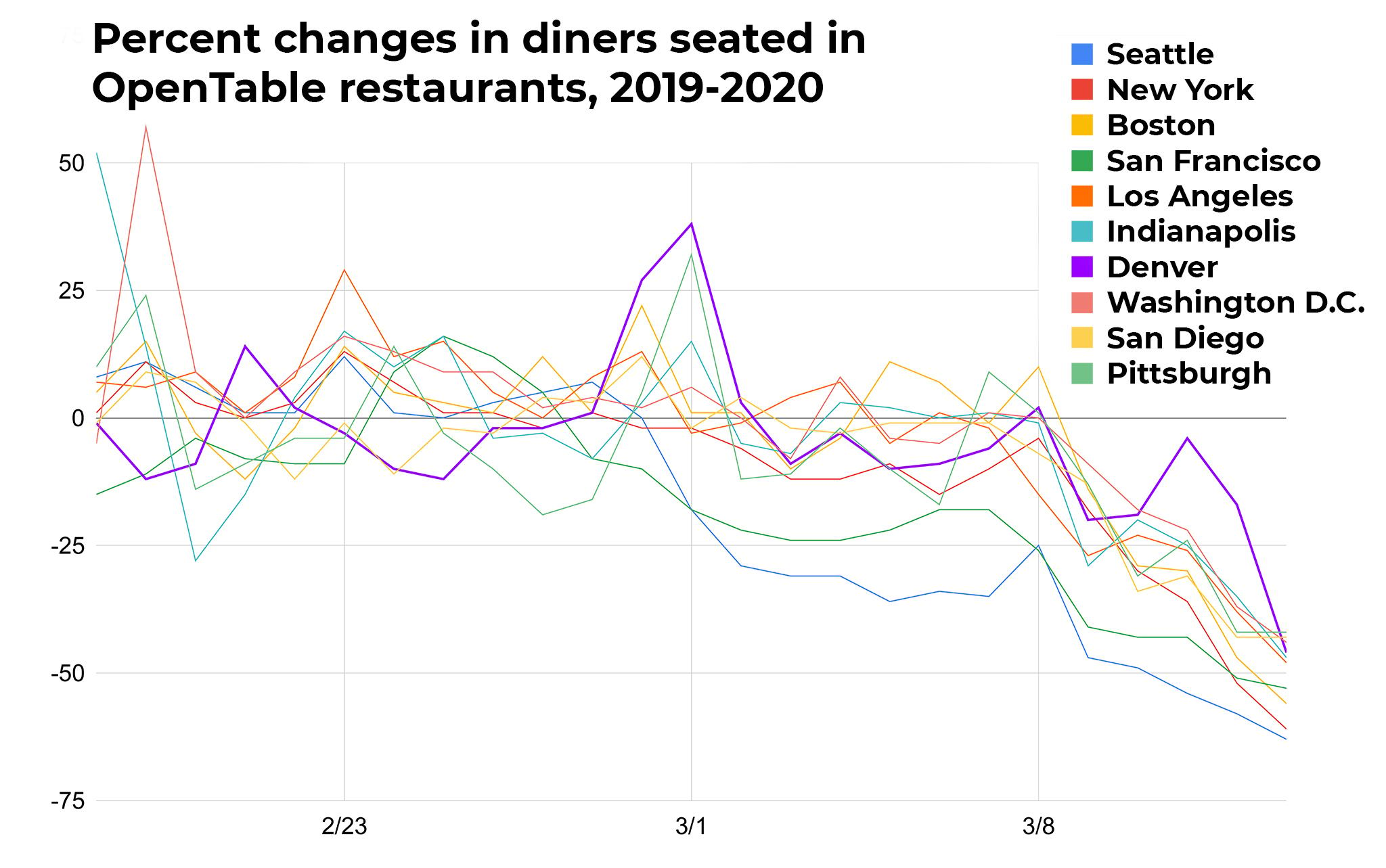

Reservation site OpenTable recently published data from its service after it saw a "severe reduction in diners" across the 60,000 restaurants it serves worldwide. The figures compare the number of people seated at restaurants in the last few weeks to those dates a year ago. It's a common method that restaurant managers use to project sales on any given day of the year.

When we charted the ten U.S. cities with the biggest drops between March 13, 2019 and 2020, it became clear that the numbers of people dining out have plummeted in all ten. Through the last two weeks, all seatings at OpenTable restaurants in these cities dropped beneath their 2019 benchmarks.

Denver ranked seventh for worst performances on March 13, with a 46 percent drop between this year and last. Seattle had seen the worst loss, with a 63 percent decrease of people sitting at OpenTable restaurants.

While area eateries are taking safety precautions - and though the Denver Post reported "its still OK" to eat at local restaurants - OpenTable's figures show people are staying away. What waitstaff has to lose from this scare is up for Rai and his gig workers to gain.

Many workers have dealt with a tough market in Denver. If things continue to get worse, lost cashflow could result in catastrophe.

Even as drivers in Rai's Facebook group continue to wipe down their cars, sanitize their hands and hope for drunk crowds in LoDo, not everyone has decided to keep working.

"As a 60+ Lyft driver with a second risk factor (diabetes), I've decided it's in everyone's best interest for me to lay low for a while and catch up on domestic projects," one member wrote.

"Except for total isolation, you will be at risk. Isolation is not an option for me," said another.

The gig economy has always been tumultuous, Rai said, but people are starting to wonder how they might survive if the COVID crisis drags on too long and if more sectors shut down.

"With gig work, you've got to have a nest egg that you create real fast. The first thing you should be doing is setting aside 20% for a fund that should cover you for two to three weeks or cover emergencies," he said. "That's tough because, you know, a lot of us live hand to mouth."

Officials estimate there are as many as 45,000 gig workers across the state. They will find fewer opportunities to make money if customers continue to avoid going out and stop using Lyft and Uber for a while. Not everyone relies completely on this work to make ends meet, but members of Rai's group are bracing for things to get worse.

"The governor just banned all public events of 250 people or more that'll definitely have an impact on business," one person posted.

Even though he supplements his income by building websites and performing with his band (what he considers his "real job"), Rai said he recently had to move from the Highlands to Capitol Hill in search of a place he could afford. This is a reality facing many people he knows. If a gig worker decides they have to stop driving or delivering - either because they're sick or afraid they might catch the virus - Rai said it can be "catastrophic."

Denver estimates 30 percent of renters in the city are "cost burdened," meaning they spend at least 30 percent of their income on housing. Half of those people are thought to be "housing insecure," meaning they spend at least 50 percent of their cashflow on rent.

Lyft has committed to pay drivers who test positive with COVID-19 for their lost time. But those who aren't sick and decide to take a break, and those just dealing with a potential downturn in gigs, may have to find other ways to make ends meet.

"One word and one word only 'food deliveries,'" one person posted to Rai's drivers group. "I haven't did this in years but I'm guessing it's the time for it."

For now, anyway. The delivery boon could evaporate if more restaurants start to close. Last week, Italy moved to lock down all shops and restaurants as COVID-19 cases rose. Over the weekend, France and Spain followed suit.

The virus has not forced these changes in the U.S. But speaking for the White House Coronavirus Task Force in a press conference on Saturday, Dr. Anthony Fauci told reporters: "We have not reached our peak."