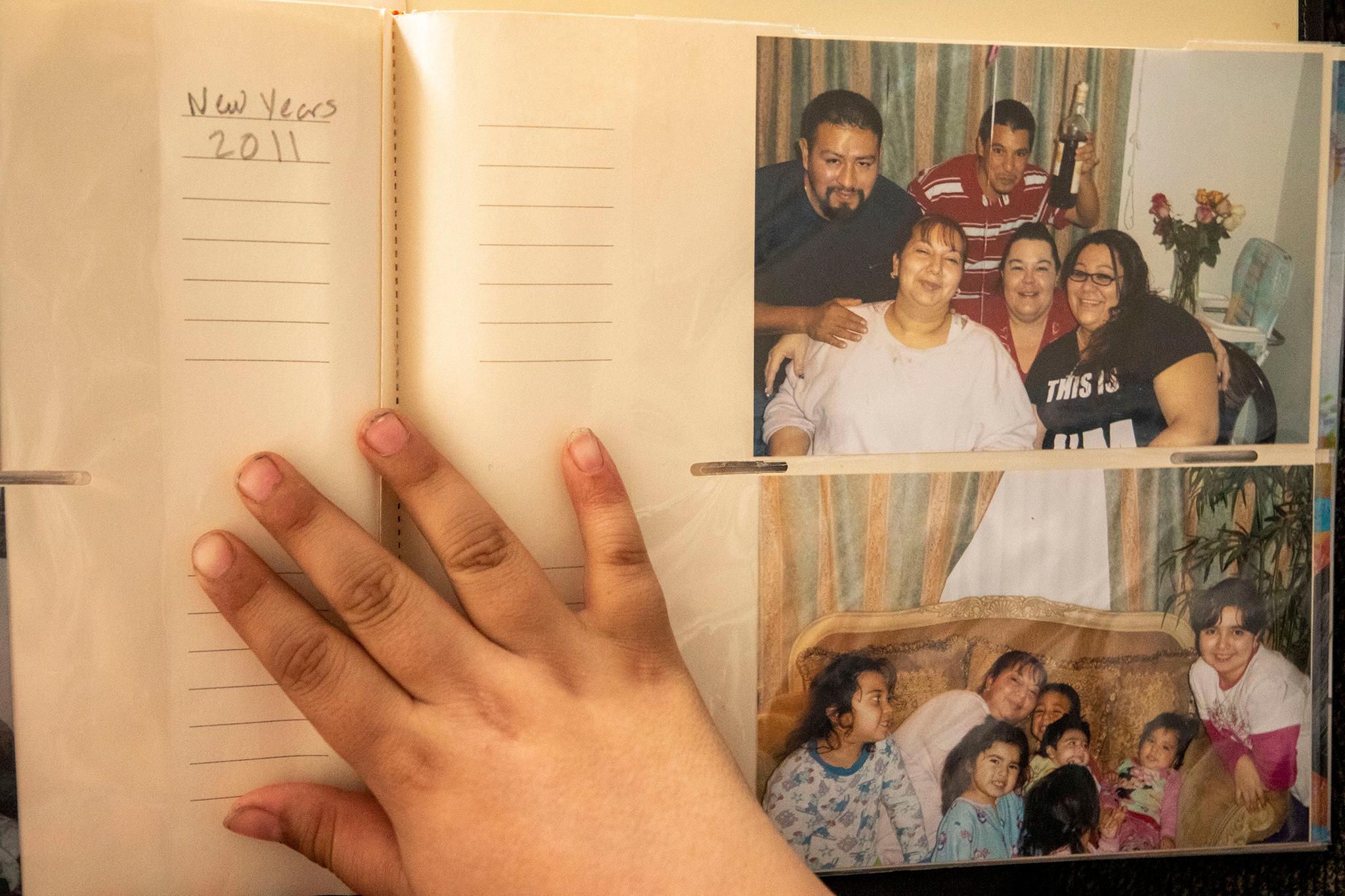

When her husband was deported in January, Christina Zaldivar couldn't help but feel a pang of relief.

It had been ten years since Jorge drove her Impala into a guard rail and earned the attention of federal immigration officials. Ten years of gathering documents for appearances in court, of living frugally to afford the attorneys, of check-ins with ICE and seemingly endless uncertainty and pain.

And then, last November, agents finally detained him. Jorge spent three months in ICE's immigration prison in Aurora. He video chatted his family when he could, but he mostly spent time waiting and arguing with guards about how much they gave him to eat. Jorge is diabetic, and his family worried he was withering away.

But Christina suddenly became a single mom, and she still needed to tend to her day job and Jorge's ongoing immigration case.

Though her two eldest daughters live on their own and could help with Francysco, 10, Aanahny, 12, and Dyego, 16, after Jorge was taken away, Christina felt stretched thin. There were so many play dates and Sunday school lessons and lunches to make. And then there were all the spaces in her life left empty by Jorge's absence. Small chores began to feel like gaping holes in her schedule. The cars needed fixing. The mortgage needed paying. It was Jorge who received the kids after school, cleaned up after them and helped with homework.

"I have to be a mom first. I have to be a dad first. I don't know how to do both," she said.

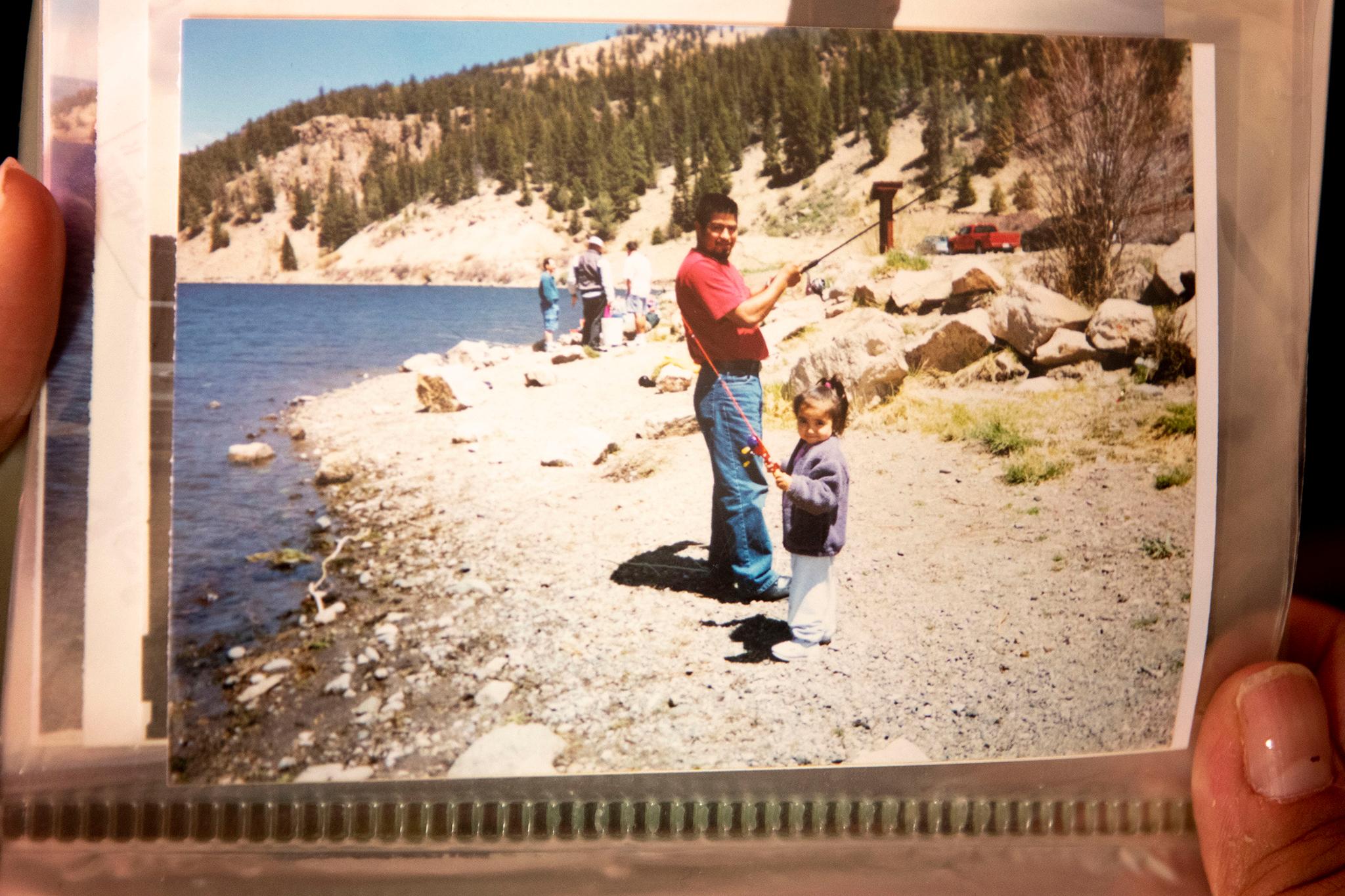

Christina was still working to pull herself out of the violent relationship with her ex-husband when she met Jorge. Her sister had convinced her to go dancing at a club off Morrison Road, and when she decided to dance with a man, she needed someone to look out for her shoes.

"George is just standing there like the old-school Indian cigar chiefs," she recalled (she calls him George). "And I'm like, 'Hey can you watch my shoes?'"

He said yes. When she finished her barefoot steps on the dance floor, he asked for her number.

"I couldn't get rid of him after that," she said.

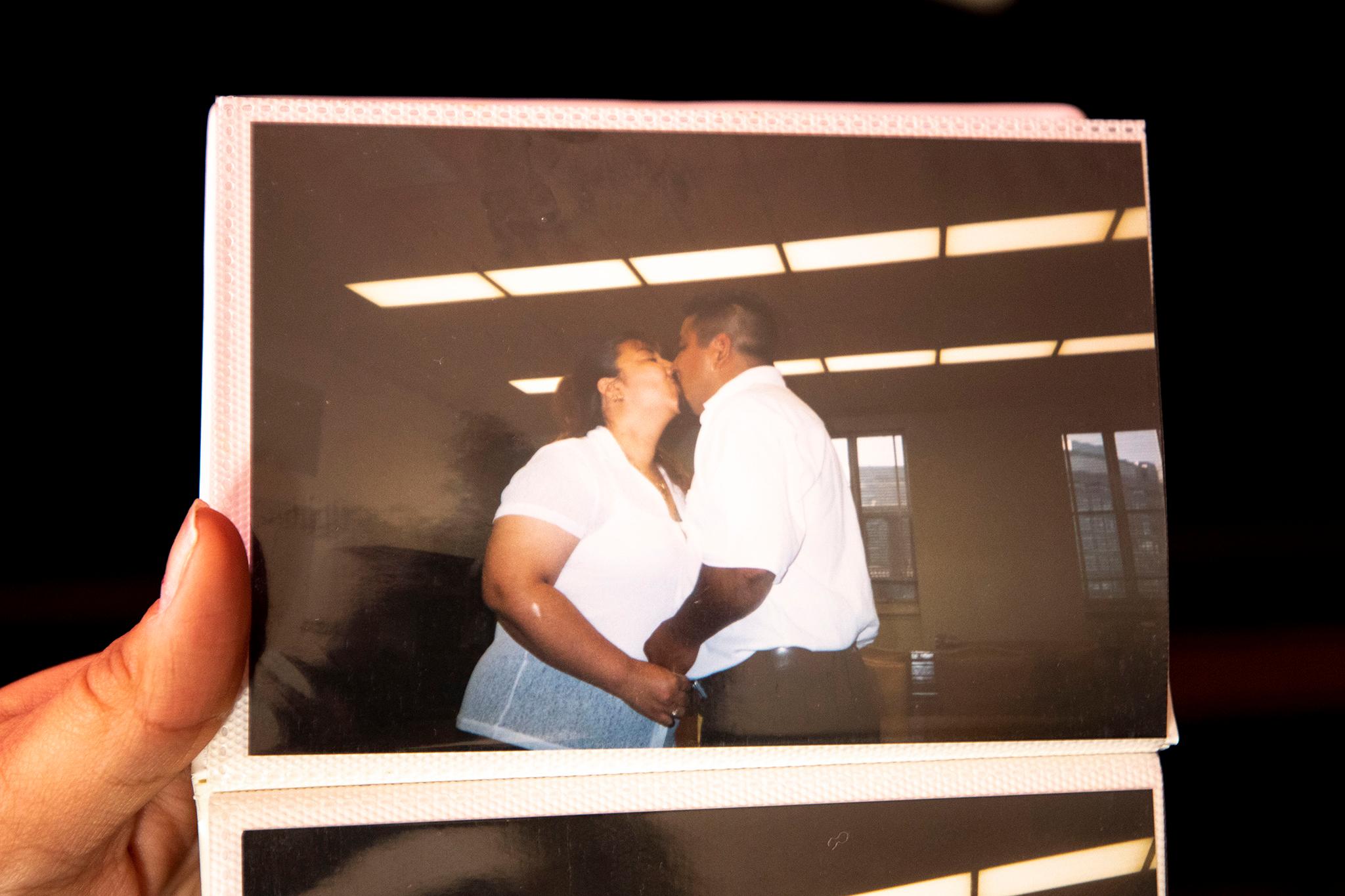

They married in a courtroom inside the City and County Building. Dyego and Christina's eldest daughters, Josefyna and Yolanda, were their only witnesses. Christina said she wanted to be married in a church, but they needed to save money to get Jorge's residency in order.

Christina was born in Denver and raised on the west side. When they began to plan for their family, she worked to make sure her kids would land on their feet when they left the house and stay close by.

They bought a house in Bear Valley and then a condo nearby. They'd keep the condo until the eldest, Josefyna, was ready to buy her own place, then sell it to her. When Josefyna was ready for a proper home, she'd move out and sell the condo to Yolanda, the next in line. Though Christina said Yolanda "messed it up" when she decided not to move into the place, the property was still in the family. Her plan to keep all five kids nearby could still be saved.

But when it became clear Jorge would be sent back to Mexico, the dream began to fall apart.

"I worked so hard to keep this stupid family together," she said, exasperated. "I have to be the one who tries to fix it, and I'm trying fix everything. And I'm not superwoman, but I sure feel like it sometimes."

Christina has become something of an expert in immigration law over the last decade. She's been intimately involved in every appeal and filing to keep Jorge by her side.

The particulars of Jorge's case, like immigration law itself, are complicated. He and Christina paid a notary to process his initial residency paperwork, but the man they hired made a mistake. That became a problem later when they flew across the border to complete the next step. Jorge also had a note on his criminal record showing he was once accused of stealing a car. Christina said the incident was a misunderstanding after he drove a drunk friend home, and that the charges were dropped. But the accusation remained, and that's what immigration officials saw when they denied his request for residency after they were married.

These initial circumstances led to a cycle of interactions with federal officials that resulted in his removal. Christina described it as dominoes falling, one after one. She's still paying attorneys, and she has hope he'll be allowed to return to the United States. But, for now, she must wait for the government to hear their next appeal. She's spent years waiting for answers. The uncertainty has been unnerving.

"You can't make decisions based on a maybe," she said. "You're either all in or all out. Tell me he's not going back so I can sell all my stuff."

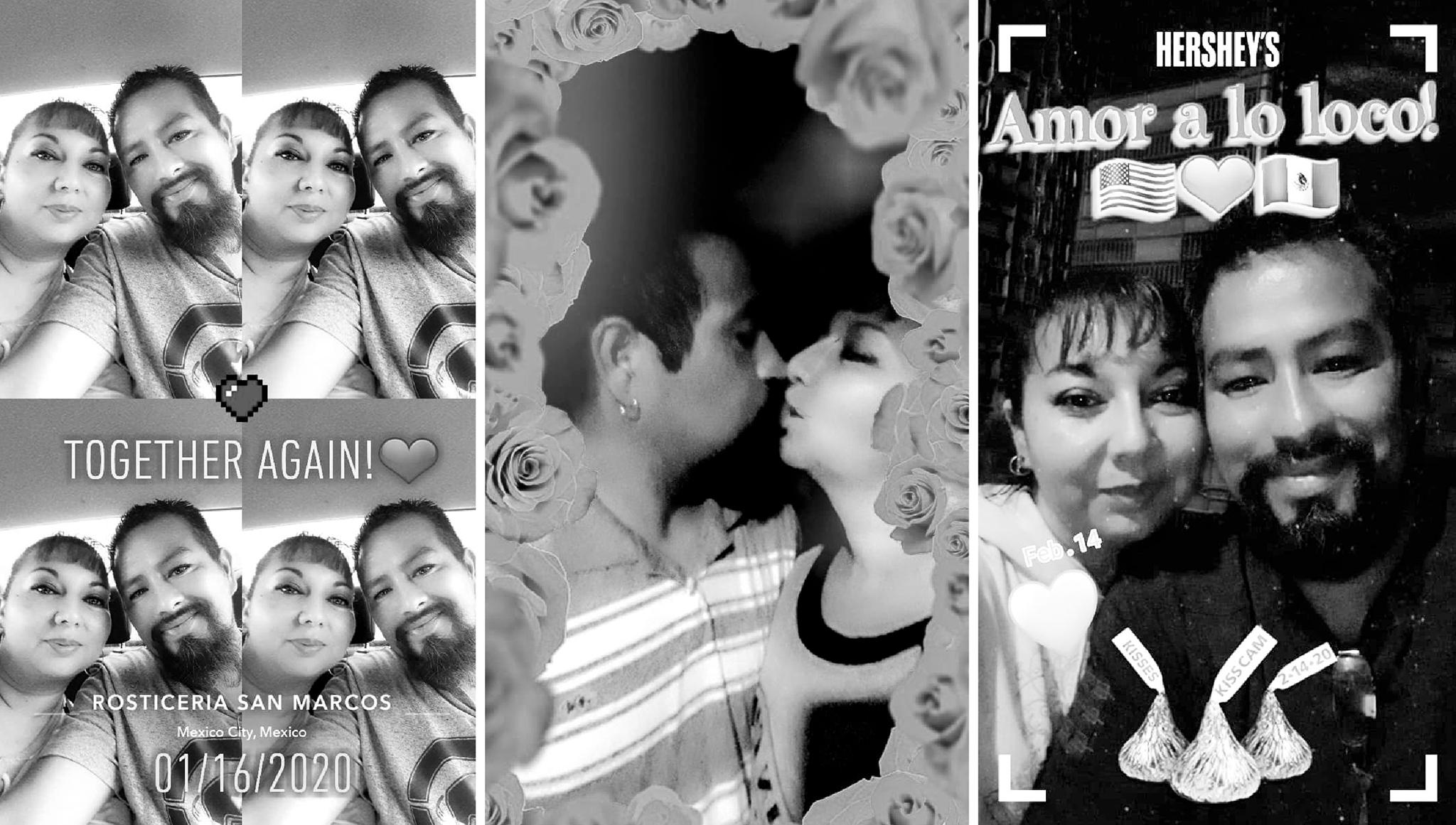

Christina was waiting for Jorge when the plane carrying him and two agents landed in Mexico City. She'd booked a flight based on the date officials told her he would be deported, but it was delayed and she spent a week alone with his family, sitting quietly in a new, noisy city. She didn't like it there, but she needed to be with her husband.

She was glad to see him when he arrived. It was the first time they could touch in months. But her joy was tinged with sadness and frustration.

"You're happy to see him, but at the same time we're not supposed to be here," she said.

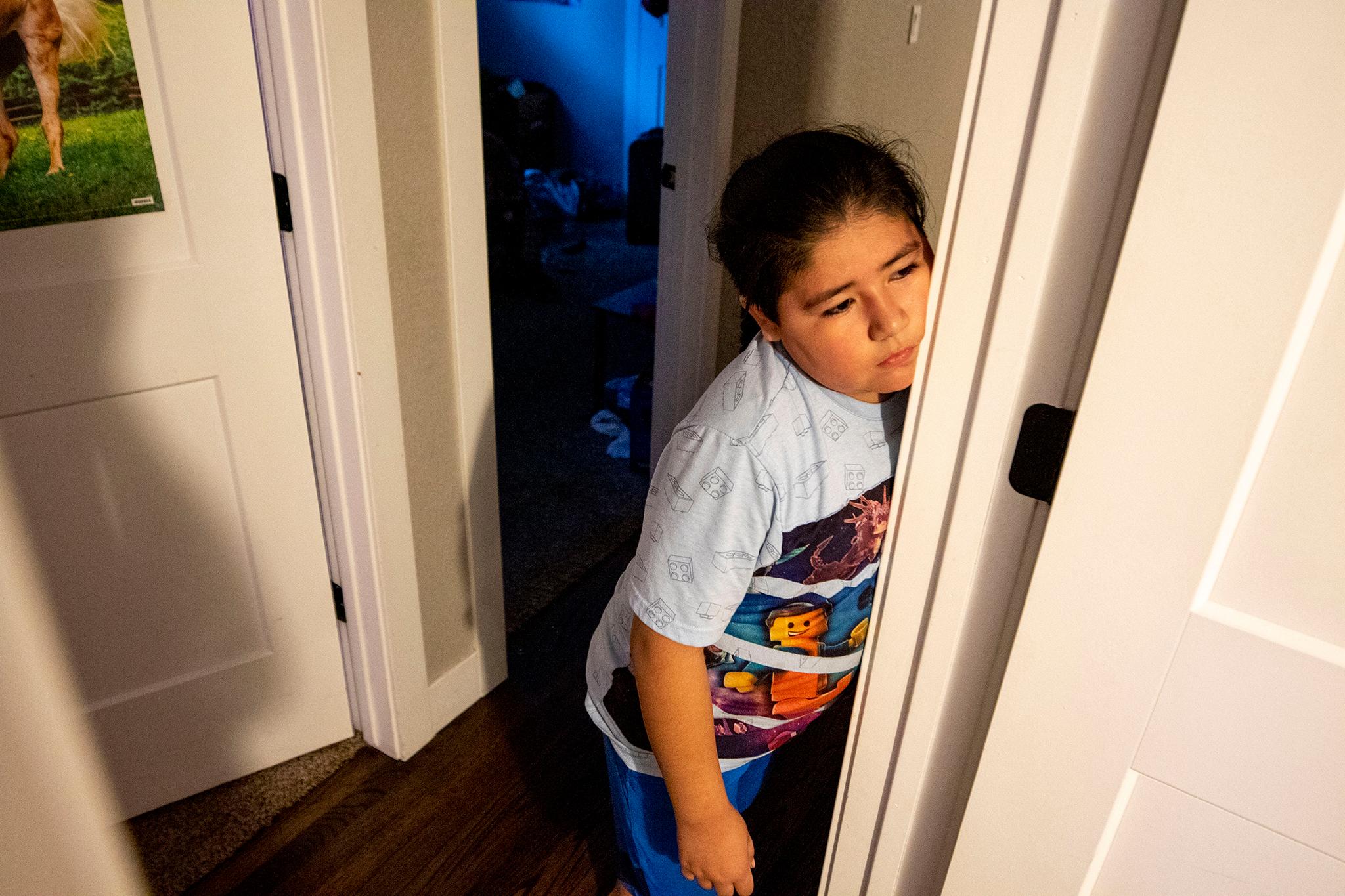

Christina worried about the kids. Francysco cried heavy tears when she dropped him off at school the morning she left. He'd been a wreck since Jorge left, crying everything he thought about his father. Christina said he'd been seeing a counselor at school, but the counselor needed to refer him to someone else. Francysco's troubles were just too heavy.

Later, she'd learn Francysco was bullied at school while she was gone. A classmate, she heard, said to him: "Your dad left you because he didn't love you."

Thinking about it made her cry, too.

She returned to Denver a week later, but she'd soon go back to Mexico for Valentine's Day. And then, in March, she planned to take the three youngest kids with her on yet another trip. She risked losing her job to make these visits. Her employer, a medical clinic, denied her emergency leave, so she was forced to use vacation time. She wasn't dealing with a death in the family, but it felt that way sometimes.

"They said it's not a catastrophic event," she said. "What do you mean it's not catastrophic? It's catastrophic to me."

Her luggage was always packed when she was home in Denver between visits. She spent time gathering food and home goods for Jorge when she wasn't playing catch with Francysco or taking Dyego to his job at a car wash. It exhausted her.

"I just want to feel normal," she said. "I just want a day off. A legit day off."

It's been a lot to juggle, but the responsibility has given her a place to channel her frustration.

"Drugs ain't gonna fix it. Alcohol ain't gonna fix it. Moping in my room, pretending that I'm depressed - it's all going to make it worse," she said. "I just have to make the best of the worst situation."

There was a time, not long ago, when Christina would never have imagined living anywhere besides Denver. But today she faces a new reality, and she's begun to consider the unthinkable.

She's still committed to fighting Jorge's case, but she's prepared move to Mexico if it doesn't work out. Francysco and Aanahny said they'll join her, too, though they'd not so much as visited the country when they said they'd go. They were excited at the prospect, not so much because they'd experience a new place, but because they could be with their dad.

"I'm not scared,' Aanahny said, "but I shouldn't have to go."

Last Monday, Christina, Francysco, Aanahny and Diego flew to Mexico City. While the kids were only supposed to stay for a week, their plans changed when the U.S. announced travel bans to stem the spread of COVID-19. Since schools are closed, there's no rush to get back.

When the kids caught sight of their dad at the airport, they screamed and sprinted to meet him. Christina said she melted as she watched them sob and embrace.

She's relieved they made it out of the U.S. in time. If they were stuck social isolating in Colorado, she said, it would have been "mentally and emotionally worse" for all of them.

Christina has filed the initial paperwork to become a Mexican resident. She hates the idea of selling the house in Bear Valley and leaving her two eldest daughters and her grandchildren behind. But she's determined to close the distance between her and Jorge. He was there for her in Denver, now she will be there for him in Mexico.

"He gave all he could for the 20 years over there, so what do I have to lose?" she said.

Correction: Jorge Zaldivar's name was misspelled throughout and corrected.