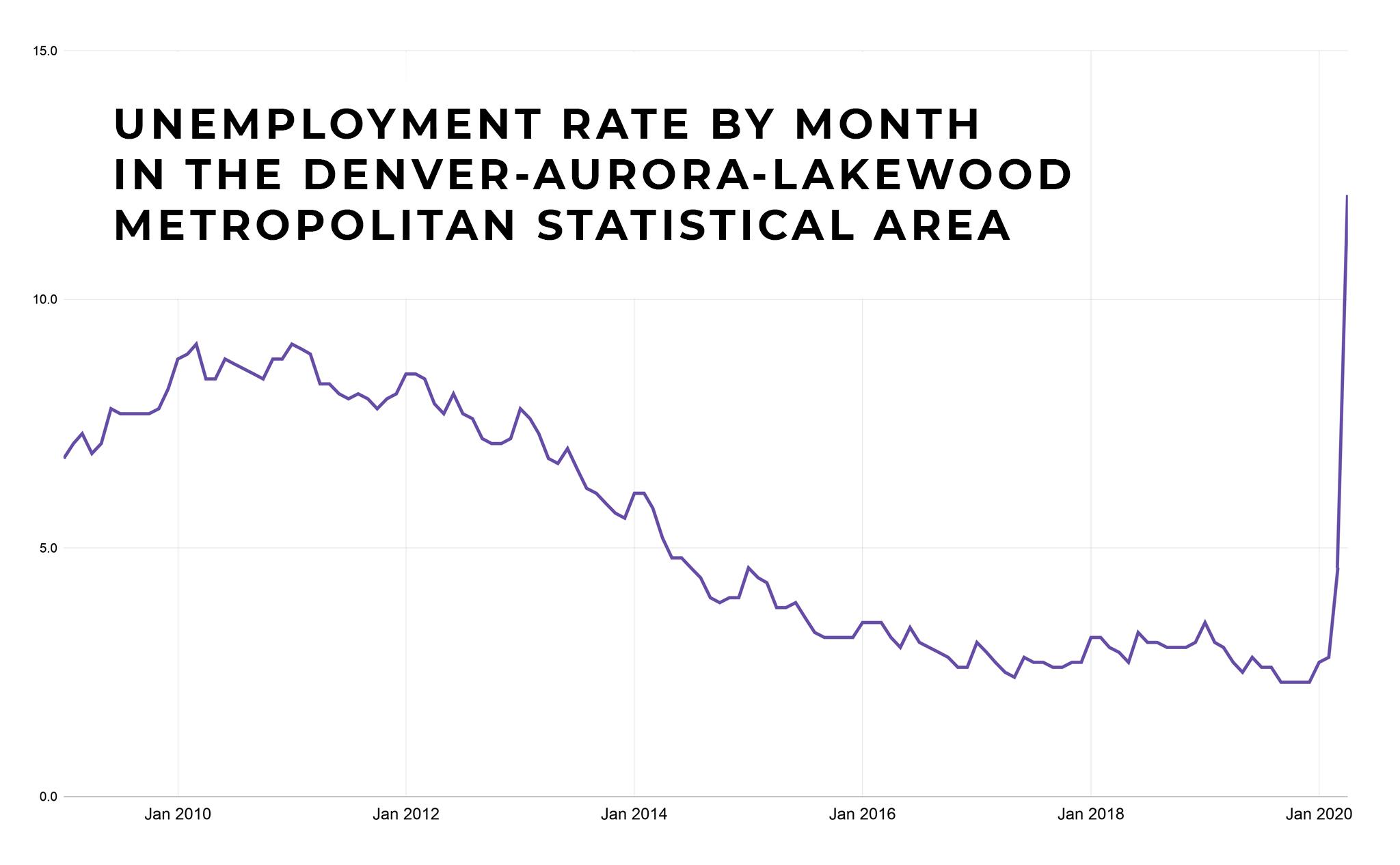

The unemployment rate in Denver climbed to 13.2 percent in April, according to data released Friday by the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment.

The metro area as a whole -- Denver, Aurora and Lakewood -- also took a punch, with 12.1 percent of the labor force looking for jobs but unable to find one. Metro Denver's unemployment rate peaked at 9.1 percent during the Great Recession, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

About 55,000 Denverites who were looking for a job in April did not find one. Regionally, the number of people out of work approached 200,000. While commerce has started churning again since then, online job postings were down last week more than 56 percent compared to the same period last year, said Lisa Martinez-Templeton, an economist with the Denver Department of Finance.

"It's not a good sign, I would put it that way," Martinez-Templeton said.

Widespread unemployment and a hard brake on city revenue -- both of which trump the city's last downturn at its peak -- are enough to lead Denver Chief Financial Officer Brendan Hanlon to assume a recession.

"We don't have the data to prove it because the data lags," Hanlon said. "But ... that's how we're treating it, and that's why we're looking to take action now and make thoughtful changes to how we spend our funds."

Denver's government is cutting department spending and making employees take furloughs to close a $226 million budget gap. As the city's second-largest employer, the government's shortfall can ripple throughout the local economy by reducing employee spending power and delaying big job-making projects like the final phase of the National Western Center redevelopment. Large construction projects funded with a 2017 voter-approved bond could slow some of the bleeding, Hanlon said.

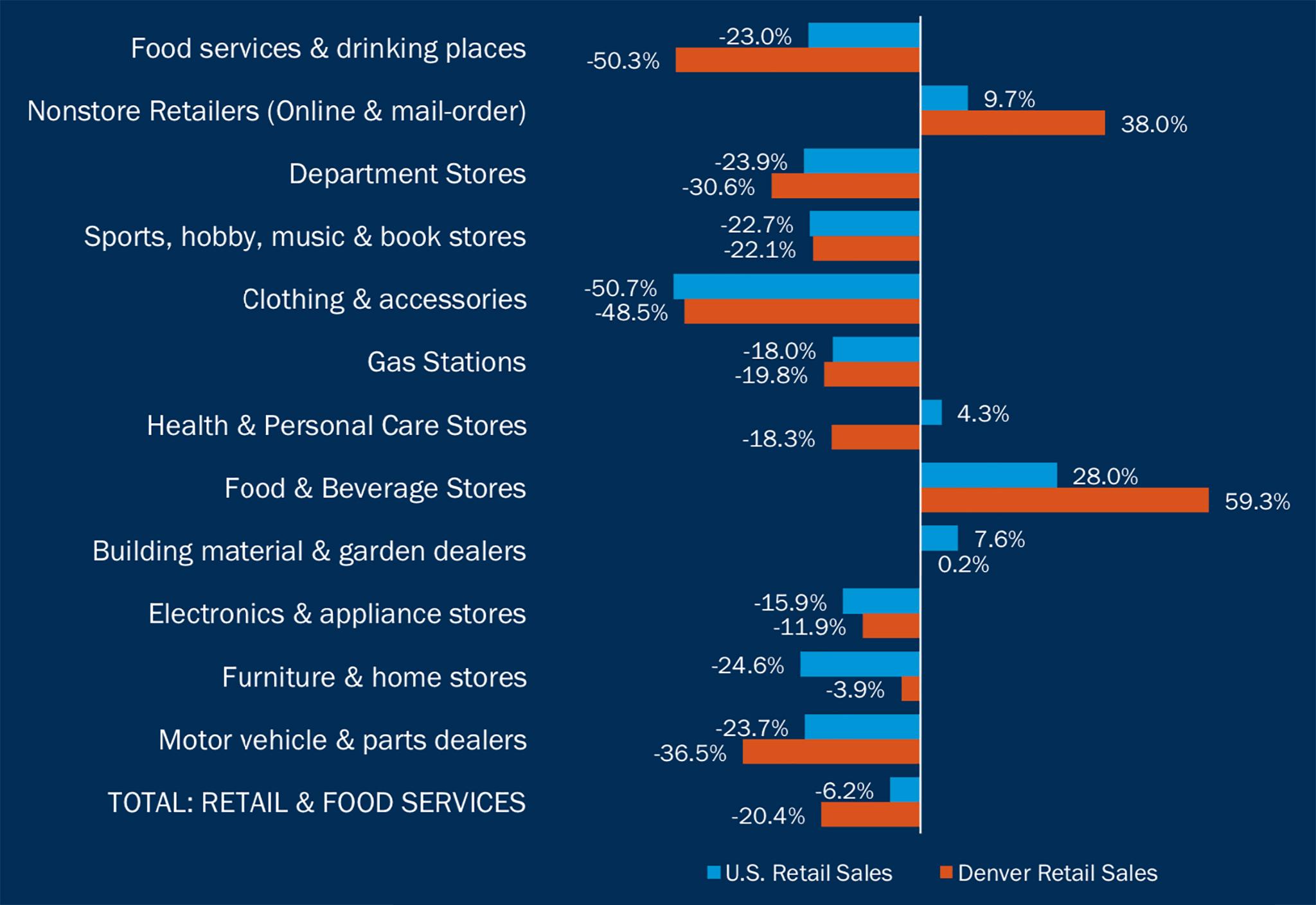

Still, Denver's private sector is suffering the most right now. The tourism industry is almost nonexistent, evidenced by hotel taxes plummeting 63 percent. Sales, in general, are reeling. COVID-19 has hit the city's bars, restaurants, car dealers, and brick-and-mortar shops the hardest. According to the city's finance department, most of those sectors have performed especially badly compared to the rest of the United States.

Online job postings for Denver's hardest-hit industries are down about 73 percent over this period last year, according to the finance office. Denver's grocery, liquor and online sales, however, performed better than the rest of the country.

Eric Hiraga, who heads Denver's Office of Economic Development and Opportunity and is on the city's recovery task force, said a fast pace of relief will be key. He cited grants sent to local businesses last month -- a second round of relief is coming soon -- that will aid about 500 business owners. Denver is also looking into property tax relief and other programs, like creating outdoor dining spaces, to jump start the economy.

"We need to work really fast and get the programs and the dollars to the people in need as soon as possible," Hiraga said.

People need to have money to spend money, but they also need to feel safe going places to spend it.

There's no magic button that restarts the economy during a pandemic, said Andrew Friedson, an assistant professor of economics at the University of Colorado Denver. Even if people have money, they must feel comfortable going out into the world and spending it. Until then, consumer confidence will continue waning, he said.

"I don't think we're at the bottom yet," Friedson said. "I think that people are starting to think about how do we restart the economy as opposed to asking the question, 'How do we stop the bleeding?' They're trying to get us into the recovery when we're not finished with surgery."

Reigniting the economy, even part-way as Denver has done with its safer-at-home orders, inherently risks a second wave of the coronavirus as more people come into contact with one another. A COVID-19 resurgence in the fall is possible. But Hanlon said Denver won't fully reopen without the public health department calling the shots.

"We have public health experts that are advising the city, our business community, the public as to how to operate in a safe fashion," Hanlon said. "So I think what we're trying to do is be thoughtful about how we open up in a thoughtful, safe and sustainable fashion. You don't want to rush out and not have taken those precautions to make sure that people feel comfortable, because a lot of what we're experiencing here is psychological as well."

The big thing keeping Hanlon up at night, he said, is uncertainty.

"When it comes to financial sustainability, it requires keeping an eye on the horizon, which is a stressful proposition right now," he said. "I think none of us really know what the next six, 12, and 18 months is going to look like."