On Thursday night, as protesters rallied around Denver calling for the police officers involved in George Floyd's death to be charged with murder, their confrontations with cops often turned violent. Groups took over streets, even closing I-25 under the Highland Bridge. A few protesters threw water bottles and rocks at police. Officers dressed in riot gear responded en masse, deploying tear gas and pepperballs to disperse crowds.

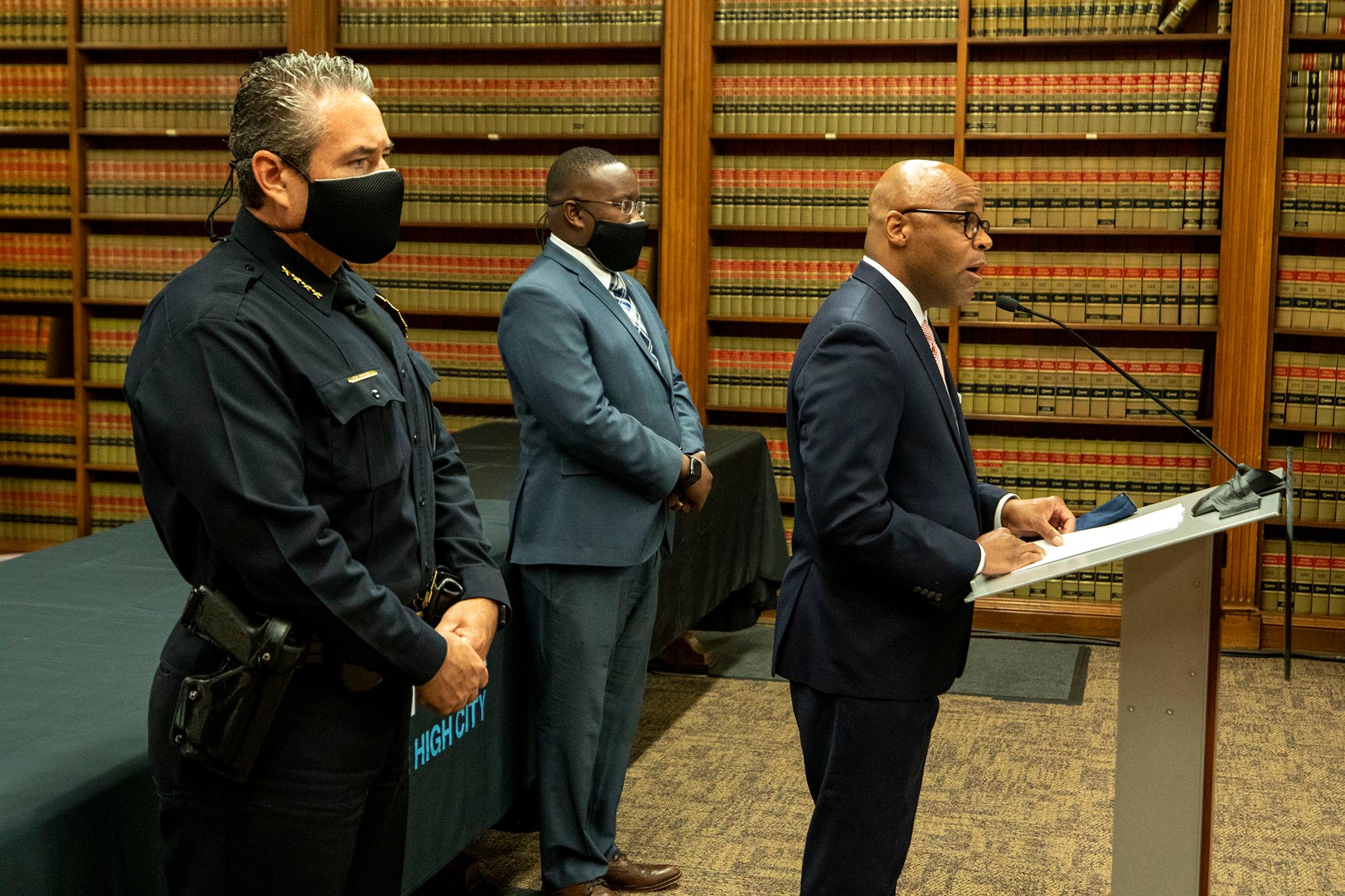

During a press conference Friday, police chief Paul Pazen said officers arrived at Thursday's protest in their regular uniforms. But a handful of incidents -- including when a protester hit an officer in the head with a rock -- changed DPD's approach. Cops in riot gear were shuttled in. Tear gas was deployed. Protesters and passersby were hit with pepperballs.

Behind DPD's actions yesterday was a guiding document, a plan years in the making that lays out the kind of force officers are -- and are not -- allowed to use in Denver. DPD's use-of-force policy is the product of years of community upheaval over violent confrontations between police and citizens that resulted in numerous deaths and millions in settlements paid out by the city.

"We respect peoples' right to protest and freedom of speech," Pazen said Friday. "Protests like this one, we encourage to be done safely. We provide officers to ensure that our protesters can get from point A to point B safely. We block traffic, we work with organizers and help them get their message heard.

"However, last night, when the protest crossed over into destructive, dangerous and criminal behavior, that is no longer acceptable, and it requires law enforcement intervention."

On Friday, Pazen and Mayor Michael Hancock praised officers' response to Thursday's protest, saying they acted with restraint after a reporter asked whether the department followed the use-of-force policy.

But Pazen's later claim that the policy was "created by this community" in a proactive way to prevent tragedies misses important context that longtime criminal justice reform advocates in Denver worked hard to address.

Joe Szuszwalak was at Sherman Street and 14th Avenue on Thursday, watching protesters peacefully chat among themselves.

He said he didn't see protesters throw anything or attempt violence before police suddenly started using tear gas and pepperbullets, shooting at "point-blank range for no apparent reason, without provocation," Szuszwalak wrote in an email to Denverite. "The only escalation I saw from protesters (water bottles thrown towards police) was AFTER the police escalation at Sherman/14th."

Pazen said police officers only utilized crowd-control methods when provoked by protesters. He said DPD would investigate any claims made by the public refuting that assertion.

The department will look to the use-of-force policy to guide any investigation.

The 27-page document dictates the methods police can use to restrain people, control crowds, and even shoot their weapons, and lays out the kinds of "force/control options" officers may use, including batons, chemical munitions, patrol dogs, pepperballs, "personal body weapons" like hands, knees, elbows and feet, and their voices. When possible, officers should "give clear and concise verbal commands to the individual prior to, during, and after the deployment of any less lethal weapon," like pepperballs, which are shot like bullets but filled with a powder that irritates skin and eyes.

According to the use-of-force policy, officers should not apply direct pressure to an individual's trachea or airway to reduce air intake, aka use a chokehold. The policy also says that officers that use their body weight on someone's back, head, neck or abdomen in an to attempt to control an individual who is resisting arrest must immediately stop once the person is restrained.

A video circulating social media shows Floyd on the ground with an officer's knee behind his neck. After repeatedly saying he couldn't breathe, Floyd passed out. He died shortly thereafter.

After the policy was unveiled, Pazen said every officer in the department would undergo at least eight hours of training, including virtual-reality simulators to teach de-escalation tactics in scenarios officers might encounter.

The death of Floyd, a Black man who died in police custody in Minneapolis, might have instigated Thursday's protest in Denver, but activists were quick to raise this city's own history of law enforcement abuse and violence.

It's a history so recent, Hancock campaigned on law enforcement reform when he was first elected to his role, back in 2011.

At that point, the city had spent millions of dollars in payouts to victims of law enforcement brutality. But the event that would initiate years of reform in the police and sheriffs departments happened in 2010, when Marvin Booker, a homeless Black street preacher, died after sheriffs deputies put him in a sleeper hold and tased him while he was in jail. Booker's family would eventually win a $6 million settlement from the city over his death, and a U.S. Court of Appeals rebuked officers' telling of the incident, finding that Booker never resisted deputies.

When Hancock came into office, he quickly replaced the head of the police department with Robert White. The tenured Black law enforcement officer ruffled feathers when he made top-ranking officials reapply for their jobs.

But Hancock wouldn't make leadership changes at the sheriffs department until 2014, a year after the Office of the Independent Monitor issued a scathing report about the department. After combing through several years of data, the OIM, an independent watchdog over the city's law enforcement, found that 45 percent of the complaints of serious misconduct by deputies, including inappropriate force, non-consensual touching and biased behavior, were never reported to the sheriff's Internal Affairs Bureau to be investigated.

The OIM itself stems from a violent incident involving police. In 2003, officers killed Paul Childs, a developmentally disabled 15-year-old. A year later, then mayor John Hickenlooper appointed Al LaCabe as manager of safety, the civilian who oversees Denver's law enforcement agencies and fire department. LaCabe overruled the police chief's decision in the Childs case, suspending the officer who shot him. LaCabe and other city officials would go on to create the OIM, hailed to this day by criminal justice reform advocates as a model law enforcement watchdog.

But contentious, even deadly, law enforcement encounters continued.

In 2015, officers shot and killed Paul Castaway, a mentally disabled man who had threatened his mother with a knife. Activists were stunned when then District Attorney Mitch Morrissey cleared the officer who killed Castaway of any wrongdoing. Castaway's family sued the city in 2016.

In 2015, officers shot and killed Jessica Hernandez, a 17-year-old who had been reported driving a stolen vehicle. In 2017, the city reached a settlement with her family that included a $1 million payout.

Also in 2015, a man who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia was arrested for trespassing. During an acute psychotic episode in a Denver jail, Michael Marshall was pinned to the ground by deputies, who placed a spit hood over his mouth. Marshall would choke on his own vomit. Twenty minutes later, deputies called an ambulance. Marshall had been held on a $100 bond.

All the while, Chief White was overhauling the police department's use-of-force policy. In January 2017, White released the document to the public, but it was met with swift criticism from the Office of the Independent Monitor and members of council over its lack of details and community involvement.

White "brought a majority persons of color committee together and he and his team worked with us for well over a year," said Councilwoman Robin Kniech, who was involved in the committee," going through national standards, reviewing city policies and more.

"The committee had some fits and starts, but ultimately the community policy was 95% complete when the Chief resigned," in 2018. "There were a couple final sticking points in his final week, so he agreed to leave the decision on those items and the 'adoption' of the policy to the new chief. Within days of being sworn in Chief Pazen agreed with the majority of the community's requests on those final items, and he then took a little time to clean up the final draft, but then adopted the policy within weeks/a couple months. Then there was a year of training as it was launched."

In 2019, Pazen said use-of-force incidents in the police department had decreased

That doesn't mean they've stopped. On New Year's Eve 2019, police allegedly beat Justin Lecheminant in his backyard after he drove away from them at a traffic stop. A lawsuit filed by Lecheminant, who suffered a broken nose, punctured eardrum, broken ribs and a concussion, alleges the department failed to investigate the incident.

This article has been updated to clarify the plan's adoption.