For months, COVID-19 restrictions have barred Rosy Perez from visiting her son inside ICE's immigration jail in Aurora. The pandemic, she said, has also slowed his case. He was supposed to show up for his first appearance last month.

"They canceled it because of coronavirus," she said in Spanish, "and I don't know anything. I don't have any new news about what will happen next. We're just waiting for another date. And it's super hard, it's terrible, the waiting."

Raul was brought to the U.S. when he was 5. He's a legal resident, but Perez said a couple of DUIs put him on Immigration and Customs Enforcement's radar. Last year, after his most recent arrest, Jefferson County court officials told her she could pick him up after she paid $750 to bail him out. But when he finally called her, ICE had already arrested him inside the courthouse. He'd dialed from the Aurora detention center.

That was in September, Perez said, and he's still not seen a judge. The first hearing was supposed to be May 13, but the date has now been delayed more than once.

Perez said she's been waiting for some movement on his immigration case, anything that might give her a sense of what will happen to him. But things inside are moving slowly. Navigating cases like these can be excruciating for families in normal times. The pandemic has made things harder.

Hearings inside the detention center are now often delayed or argued by attorneys working remotely to defend clients they've never met in person.

Laura Lunn is an attorney who oversees the Rocky Mountain Immigrant Advocacy Network's detention program. She's watched the Department of Justice's court inside the detention center unravel as COVID-19 cases rose in the area.

The court closed completely in March due to the pandemic. Though proceedings have begun again and attorneys are now allowed inside, Lunn said many have not been willing to risk exposure to the virus.

Congressman Jason Crow's most recent report on the Aurora Contract Detention Facility says at least 16 detainees there have tested positive since the pandemic began -- all but two are said to have recovered -- and 197 people were "cohorted," or quarantined, due to possible exposure. The quarantine numbers have jumped up and down as new cases were discovered and dealt with. This most recent report reflects the highest number of detained immigrants under medical lock-downs, even beyond February, when 138 people were quarantined due to simultaneous outbreaks of flu and the mumps.

As a result, Lunn said many attorneys are asking that hearings be postponed, hopefully to a future time when they feel comfortable going inside the detention facility.

Other attorneys, including Lunn, have attempted to participate in proceedings remotely. It's far from an ideal situation, she said. She can't pull a client aside for a quick pep talk, something she said is crucial to her practice, and coordinating witnesses on the court's limited phone lines has proven a challenge.

Plus, she said: "It's really hard to read a room."

Because in-person visitation has been suspended at ICE detention centers for months, Lunn said she's been representing people that she's never met.

The situation creates a "catch-22," she said. Clients and attorneys have to choose between flawed proceedings or longer detentions. Though she's glad judges are allowing cases to be delayed, it still means many of her clients will languish in detention.

"ICE recognizes the considerable impact of suspending personal visitation and has requested wardens and facility administrators maximize detainee use of teleconferencing, video visitation (e.g., Skype, FaceTime), email, and/or tablets, with extended hours where possible," the agency said in a statement.

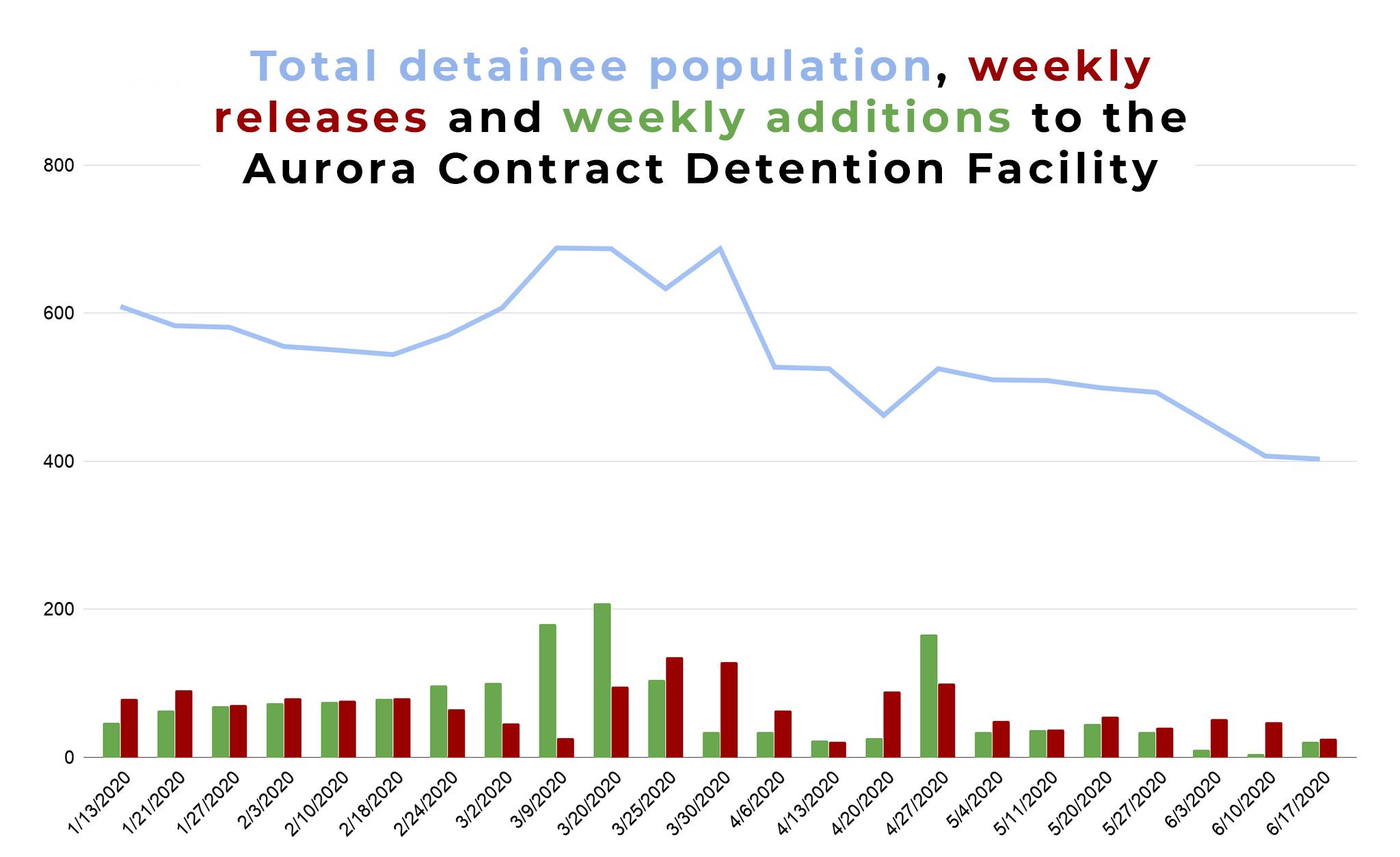

ICE has kept population numbers in Aurora lower than normal to address concerns about the virus, even below their contractual minimum of 525 filled beds. Some people were released after Lunn and her colleagues sued.

But prolonged detentions have become a "new normal."

On Wednesday, activists met on a Zoom call to celebrate Kelly González Aguilar's 24th birthday. She's a trans woman from Honduras who's waited in ICE custody for more than two-and-a-half years while her asylum claim is decided. González was first held in a unit for transgender immigrants at a New Mexico facility that was shut down after members of Congress called it unsafe. González and dozens of other trans people were transferred to Aurora in January.

Last year, her case caught the attention of Amnesty International, the human rights group that works to end wrongful imprisonment.

"Amnesty International became involved in her case last year when we found out about how long she'd been detained, because it was quite alarming for us," Alli Jarrar, an organizer with the group, said.

But while Jarrar called González's long wait "prolonged and arbitrary," she said it's been happening more and more: "This is the new normal under the Trump administration."

A few years ago, it was unusual that anyone would spend more than a few years waiting for their cases to be resolved, Jarrar said.

Lunn attributes the new normal to changes in the way the federal government approaches cases. When her clients have won bond hearings that are supposed to allow them to leave detention, she said, the Department of Homeland Security has increasingly automatically appealed. Clients in custody must then remain in detention until the appeal process concludes. Those second decisions are usually appealed, too, so the process can stretch for years. She's seen some last half a decade.

Because detainees have struggled to access detention facility courts during the pandemic, Lunn said the entire system has become pointless.

"The whole purported purpose of detaining people is to ensure people show up to court," she said, but "people in detention cannot go to court, by the virtue of the fact that they have been detained and exposed to a deadly disease."

Jarrar and her colleagues believe these drawn-out processes are part of a larger strategy. "We believe the Trump administration is intentionally holding people to try to convince them to self-deport because it's intolerable to be locked up for so long."

Perez and others believe another major moment in 2020, Black Lives Matter, could help change the system her son is stuck in.

Over a month ago, weeks before the nation's streets erupted in reaction to George Floyd's killing in Minneapolis, protesters set up a tent encampment outside of the Aurora detention facility adorned with signs reading, "Free them all." For more than 30 days, campers have held vigils each night to show support for those held inside.

While Perez hasn't been able to stay the night, she said she's come out every evening to join in their demonstrations. Without them, she said, dealing with her son's absence would be so much harder.

"Freeing them all" would likely take an act of Congress, Lunn said, though she added ICE has discretionary authority to release people if they choose to. But legislative action on immigration issues -- whether for DACA or detention -- are hard to come by. Lunn pointed out the Immigration and Nationality Act hasn't been amended in almost 25 years, even though problems with the system have gotten more complicated through the decades.

Perez expressed hope that policy changes stemming from the recent protests against racism and police brutality might also spill over into immigration issues.

"This moment is so important. It's time. It's time that people get involved, that they stand up. There are so many injustices in this world that we live in ... and I'm so glad to see people getting out and getting into the street and being a part of a movement for justice," she said. "They're breaking people, they're destroying families, they're destroying our family and it needs to stop."

Update: The numbers of people cohorted, cited from Congressman Crow's transparency report have been updated from 91 to 197, since his most recent report was released just after this story was published.