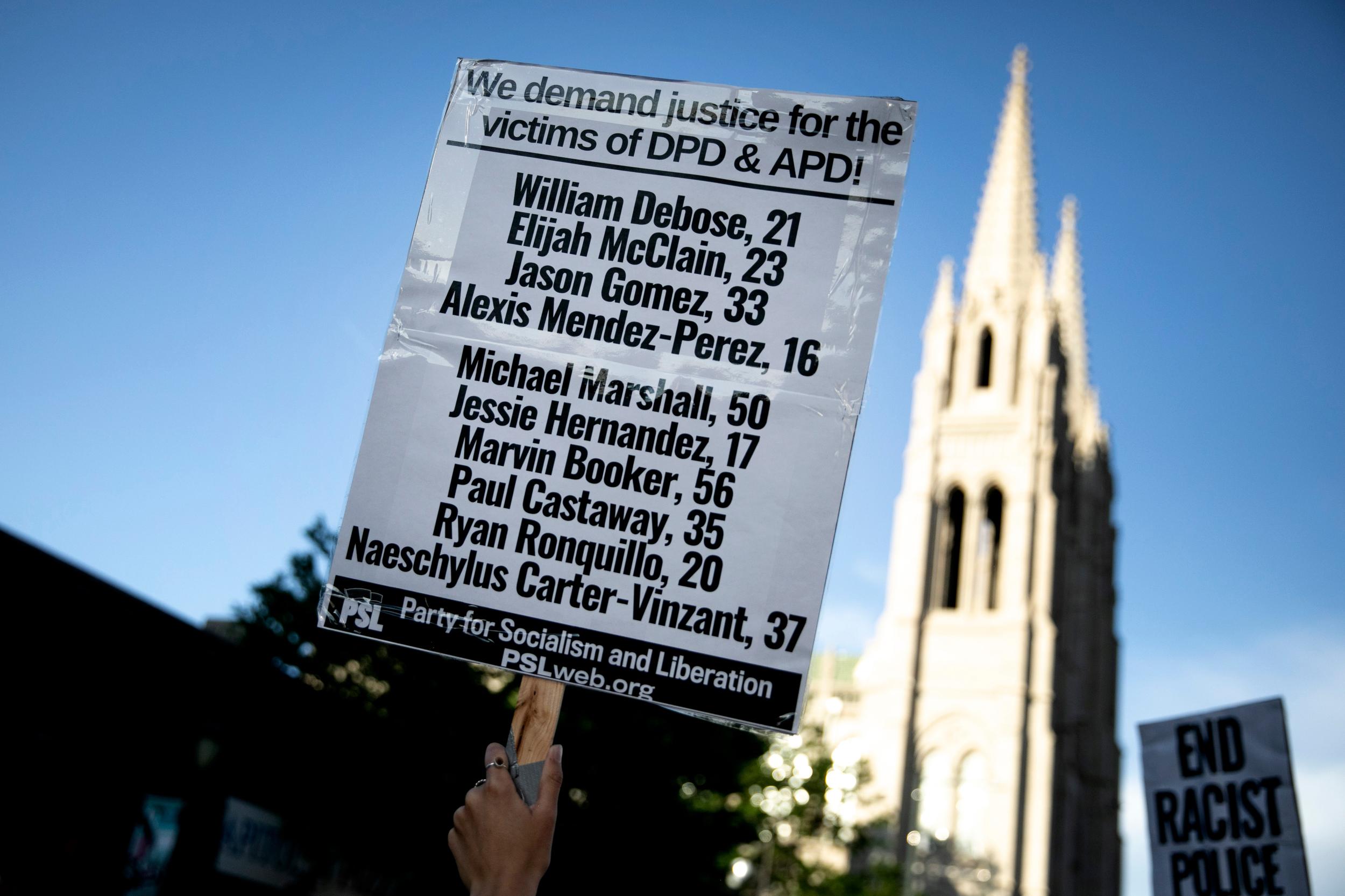

On June 12, amid almost daily protests against police violence and racism, hundreds of protesters once again took to the streets in Denver. They wound up outside Denver District Attorney Beth McCann's home, chanting: "If we don't get no justice, then Beth don't get no peace."

They were there to call on McCann to charge the officer involved in William DeBose's death. DeBose died on May 1 near a library in West Colfax after he was fatally shot by an officer who said DeBose had pulled out a gun. DeBose had been followed by police for speeding.

McCann issued her decision six days after protesters showed up at her home, and it was the same decision she's made in every case involving police officers using deadly force since she was elected to office: Her office determined the shooting was justified.

While it wasn't the outcome protesters had hoped for, it wasn't entirely surprising. District attorneys rarely file charges against police officers involved in deadly incidents. In the 309 deadly incidents involving police in Colorado between 2014 and 2019, a CPR News investigation found all but two were found to be legally justified by local prosecutors or grand juries.

It's been nearly 30 years since a Denver police officer was charged for an on-duty fatal shooting. Officer Michael Blake was charged with second-degree murder after he shot and killed Steven Grant in 1992, though he was acquitted.

Since 2005, data from the Police Integrity Research Group showed only 35 officers around the U.S. have been convicted of a crime for a fatal on-duty shooting.

As University of Denver criminal law professor Ian Farrell put it, prosecutors and cops are basically coworkers. They rely on one another do their jobs, as law enforcement works to investigate cases and present them to DAs, who then make decisions about appropriate charges.

"It's like you're faced with a position of having to treat your coworker as a murderer," Farrell said.

Prosecutors tend to give police "an enormous benefit of the doubt" when officers felt their lives were in danger, Farrell said.

"Prosecutors give police enormous deference when it comes to whether their beliefs were reasonable," Farrell said. "They accept that when a police officer says they thought their life was in danger, that that belief was reasonable, whether it was reasonable or not."

Farrell said in a first-degree murder charge, for example, prosecutors have to prove that someone (like a cop) intended to kill someone and/or they were extremely indifferent whether the person lived or died.

According to McCann's decision, police corporal Ethan Antonson's shooting of DeBose was justified. Antonson said he shot in self-defense because he feared for his life after he said DeBose pointed a gun at him.

McCann, who has served as District Attorney since 2017 and is running unopposed this year for another term in office, outlined during an interview last week with Denverite why her office wouldn't press charges against Antonson.

"This is a situation where an officer or anyone in that situation has the right to shoot, to use deadly force," McCann said. "I think that's something that we would expect. If someone points a gun at you, you have the right to shoot them, because you don't want to end up dead. It's either you or him."

McCann said her office doesn't file cases against anyone if the evidence supports "a legitimate self-defense claim."

"Under the law, the prosecution has the obligation of disproving self-defense," McCann said. "The person does not have to prove that he acted in self-defense. We have to prove that he didn't act in self-defense."

Farrell said it's relatively easy for police to argue they were acting in self-defense. Officers can make a reasonable argument that they fired because they believed someone was going to pull a weapon or did pull a weapon. And they can end up cleared in these cases even when the supposed weapon ended up being something innocuous, like a cellphone.

Civil rights attorney David Lane bluntly described why charges against police are rare. Like Farrell, he boiled it down to cops and prosecutors having to work together. Lane has filed lawsuits against halfway-house operators in Denver and recently represented a Black man who was handcuffed after someone called the police claiming he had a gun at a Safeway.

"It's only hard to bring charges against cops if you have no backbone whatsoever," Lane said. "Every prosecutor's office is dependent upon the cops to make every case they have. They're all good buddies. It's all part of the good old boy's network."

The last time a Colorado police officer was successfully charged with murder was James Ashby, a former Rocky Ford cop, who was sentenced in 2016 after being convicted of second-degree murder in the death of Jack Jacquez. Fort Lupton police officer Zachary Helbig was charged with manslaughter in 2019 after fatally shooting Shawn Billinger, but a jury found him not guilty in February.

Another reason why it can be hard to prosecute officers? Both Farrell and Lane pointed out that juries tend to side with them.

"It is hard to convince a jury that a cop is criminal. They just don't want to believe it," Lane added.

Attorney Matthew Cron was part of the legal team that represented Jacquez's estate after his death. Their research suggested Ashby's conviction was likely the first time in at least 40 years that a Colorado police officer was convicted of murder.

"The fact that he was convicted by a jury of his peers is almost unheard of, not just in Colorado, but across the nation," Cron said.

But recent cases involving deadly use of force have led to demonstrations and calls for charges against police.

Elijah McClain died in August 2019 days after an Aurora police officer put him in a chokehold and he went into cardiac arrest. He was also given ketamine as a sedative during the encounter.

McClain's death has drawn national attention. The growing chorus of calls to investigate the incident prompted 17th Judicial District Attorney Dave Young, who was in charge of investigating McClain's case, to issue a statement last week explaining why his office declined to charge the Aurora officers involved.

Calling McClain's death "tragic and unnecessary," Young said the pathologist who completed the autopsy was "unable to conclude that the actions of any law enforcement officer caused Mr. McClain's death."

"In order to prove any form of homicide in the state of Colorado, it is mandatory that the prosecution prove that the accused caused the death of the victim," Young's statement read. "For those reasons, it is my opinion that the evidence does not support the filing of homicide."

But that case isn't over. Aurora lawmakers are crafting their own independent investigation, and last week, Gov. Jared Polis appointed Attorney General Phil Weiser as a special prosecutor to investigate McClain's death. Lawrence Pacheco, a spokesperson for the Attorney General's office, declined to comment on the investigation, adding that the AG's office is "ethically bound to maintain" confidentiality. He also declined to provide details about how the investigation would play out.

"Whenever someone dies after an encounter with law enforcement, the community deserves a thorough investigation," Weiser said in a statement following the announcement. "Our investigation will be thorough, guided by the facts, and worthy of public trust and confidence in the criminal justice system."

Pacheco said that as far as anyone in Weiser's office knows, this is the first time the state attorney general has been appointed as a special prosecutor to investigate a death involving police use of force. He declined to say whether the AG's office would recommend charges in the McClain case.

How can oversight of use-of-force cases be improved?

Colorado's new police accountability bill, passed and signed this month, enacted several changes, including raising the standard for when and how police can use deadly force. The bill passed after weeks of protests in Denver.

Farrell said cops have historically been allowed to use deadly force whenever they responded to a crime involving a deadly weapon, even if the person did not pose an immediate threat. But according to the new law, now an officer can only use a deadly force if there's an immediate threat to a police officer or someone else.

Farrell said getting the Attorney General's office regularly involved in deadly use-of-force cases could help disconnect prosecutors from the officers with which they work. In Farrell's view, it helps create a system that isn't pitting coworkers against one another.

Both Farrell and Lane said an independent office or dedicated staff in the AG's office whose sole purpose is investigating and charging law enforcement officers for misconduct could be a step toward improved accountability.

"I think the more you take it out of the hands of prosecutors and a team of investigators who are essentially investigating one of their own, the better," Farrell said.