It was the Fourth of July, and 14-year-old Tyler Gordon was sitting at his easel, painting in the middle of a street in San Jose, Ca. Activity swirled around him, dancers, singers and rappers performing. Meanwhile, people armed with paint trays and rollers were bent over the pavement, creating a mural that would span three blocks.

Gordon was attending the San Jose Black Lives Matter Street Painting, one of the many events held around the country to paint "Black Lives Matter" on prominent city streets. As Gordon worked on his own canvas, "Black Lives Matter" materialized on the blacktop before him in massive white block letters.

Gordon, meanwhile, was painting Elijah McClain.

Gordon has been named a 2020 Global Child Prodigy for his portraiture work. He usually paints celebrities and has even gotten to meet some of them, like Janet Jackson, Jennifer Lopez and Alex Rodriguez. But a few months ago, when the death of George Floyd sparked protests against racial injustice around the world, Gordon started painting victims of violence fueled by racism.

"I feel like they were good people and did not deserve to die," Gordon said. "And that makes me really sad. Because I heard the story of how they died. I get really upset, because that's not what they deserve."

When Gordon heard McClain's story, he knew he wanted to paint him. He was inspired, in part, by McClain's love for the violin.

"He had a talent, and he tried to do something with that talent," Gordon said. "But before he could, he was killed.'

He wanted to showcase that talent in his portrait. He recreated a widely-shared photo of McClain playing the violin, using shades of gray when typically he paints in full color. Painting the tribute was a good experience, Gordon said -- fun, but a little sad, too.

A year ago Monday, McClain, a 23-year-old Black man, was violently detained by Aurora police. Paramedics arrived on the scene and administered a large dose of ketamin to sedate him. McClain died in the hospital on Aug. 27.

In the year since his death, he has become a major figure in the Black Lives Matter movement. His name has been recited alongside those of Breonna Taylor and Floyd at protests against racial injustice around the world.

But as McClain's story spread outside of Colorado, the world learned bits and pieces about the person behind the name. That he was an animal lover who didn't eat meat, a massage therapist, a self-professed introvert. He was a self-taught violinist who played for cats in animal shelters. He's been described by people who knew him as a kind and gentle person, traits that were evident even in his last moments. His story has inspired string players across the country to stage candlelight violin vigils in his honor. And it's moved countless creatives like Gordon to create tributes to McClain.

In the last few weeks, we've talked to artists from all over the world, from Missouri to New Zealand, about the pieces they created to honor McClain. Some wanted to recreate his essence, to show the world that he was a real, beautiful individual and not just another name to add to the list of Black people killed by police. Many saw themselves in him, as artists and introverts themselves. Some wanted their pieces to act as a call to action against police brutality and racial injustice.

Here are just a few of the art tributes that have helped to keep Elijah McClain's memory alive.

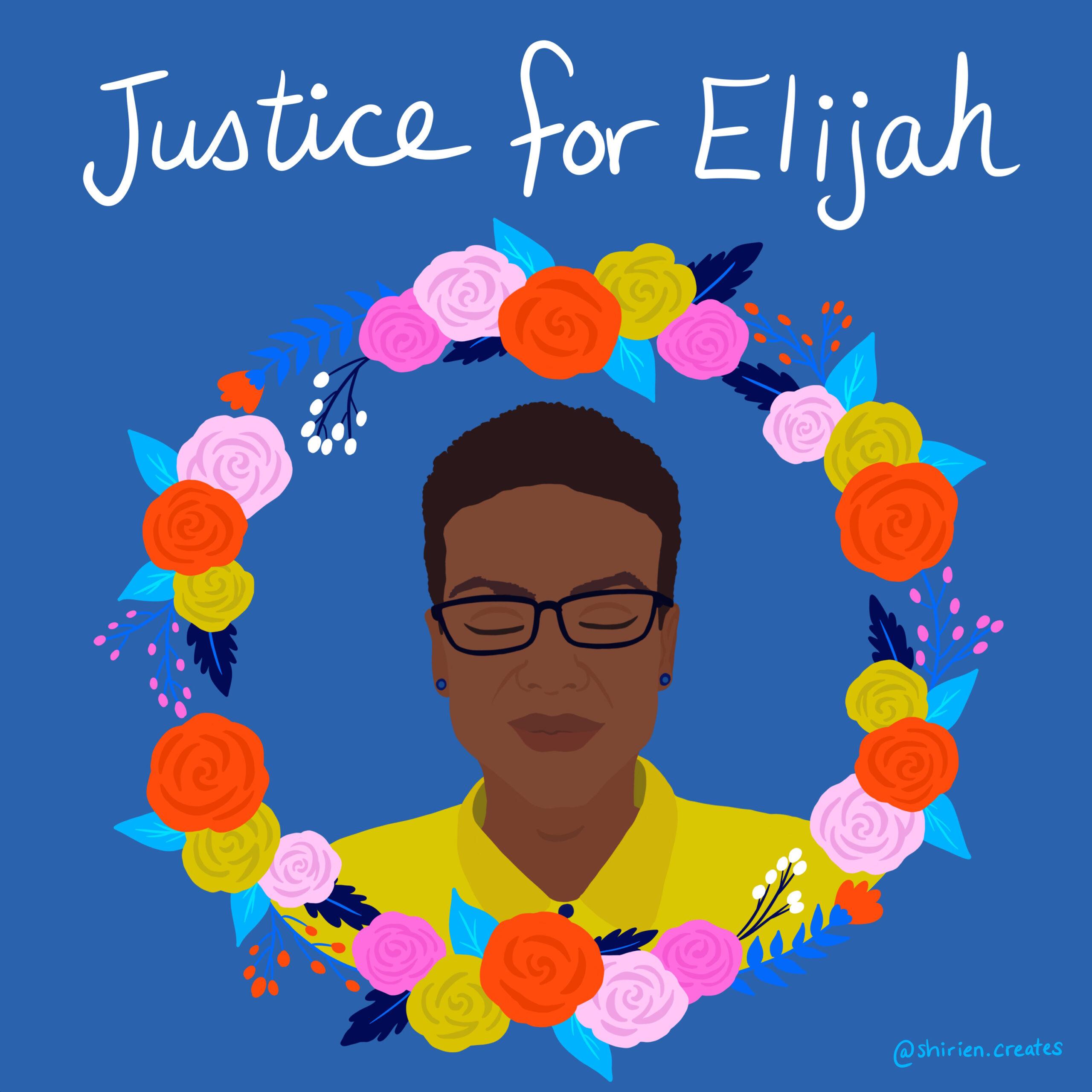

Shirien Damra was heartbroken when she heard McClain's story.

"His story goes to show how systemic racism works," the Chicagoan said. "Like, a Black man walking around in the evening can't afford to be different. You can't afford to walk around in the ski mask because you're cold."

She reached out to coordinators of the Justice for Elijah McClain campaign to see if they needed art to help spread their message. They encouraged her to create something that could be easily shared online alongside action items.

For her piece, Damra chose to use bright colors and delicate florals because, she said, that kind of imagery is rarely used in portrayals of Black men. She chose pastels to elicit a dreamy, calming feeling, and set them against bold, vibrant colors to evoke a feeling of hope and to inspire viewers to take action.

She called the flowers in the portrait an act of rebellion.

"I like to use flowers and natural elements in my work to symbolize life and growth," she explained, "which is in defiance of the systemic violence and oppression that basically seeks to quell that sort of uprising."

She wanted to create a soft, beautiful image to honor McClain's memory, to preserve his dignity. She said people often demonize victims of anti-Black violence as a way to excuse it.

"It's always like, 'Oh, they were wearing a hoodie,'" she said. "There's always some kind of unfortunate way to justify it."

Damra typically draws figures with their eyes closed. She said that resonates with Western audiences, who would look at the portrait and imagine McClain to be in a state of rest or at peace. But in Eastern art, she said, closed eyes symbolize inward reflection.

"Individually and as a society, we need to reflect inwardly if we want change," Damra said. "I hope that folks are committed to ongoing work for long-term social change after the protests have ended and after the hashtags become less popular. Because that's the only real way I believe we can tear down these oppressive systems and start planting seeds of healing and hope."

Radha Ta'ala first heard Elijah McClain's name while at home in Christchurch, New Zealand, more than 7,000 miles away from Aurora. Living on a tiny island country, she said, it can be easy to feel removed from things that happen in America.

"We grew up watching American movies, so it's almost a step away from reality," Ta'ala said. "It's so easy to go, 'Oh, that's just over there.' Especially because New Zealand is such a sleepy little place."

But Ta'ala said that the BLM movement brought up racial issues in New Zealand, particularly regarding the Māori, a group of indigenous Polynesian people in the country.

"We started to question ourselves, like, are we racist here?" Ta'ala said. "What does that mean for us? And what are we doing about it?"

She has seen how people treat her husband, who is Māori. She herself is half Indian. Police brutality isn't as common in New Zealand as it is in America, but racism certainly exists there in its own form, she said.

Hearing about what was happening in the U.S., Ta'ala suddenly felt like her work as an illustrator was trivial. She felt she needed to do something, to create something lasting that might perpetuate a conversation about race. She started an illustration series on Black victims of racial violence, intending at first to do just a few portraits. But the more she researched, the more she became aware of how prevalent police killings were.

Then she came across McClain's story.

"He just broke my heart," she said.

He reminded her of her own son, who's 13. Like McClain, he's a soft-natured, sweet boy, she said.

"I read the transcript of what he was saying when they were attacking him. And he was just so kind throughout the whole thing and almost a little bit confused. That type of person, sometimes they get misunderstood and then treated according to how they're misunderstood. And I guess for me that just hit a soft spot."

Often, when Ta'ala illustrates, she traces over a photo and adds details in her own style. With this series, though, she didn't want to trace. She wanted to do her own interpretation. She would pull up a few photos of the people she was memorializing and read up on them so she could get a sense of who they were and what happened to them. She'd mediate on all of that as she drew.

She said that while she has some control over the illustrations, it mostly feels as if they just happen, that she can't actually control the outcome. They simply come out the way they come out.

"With Elijah, I couldn't get his smile out of my head," she said.

She didn't draw him with his now-famous grin. She wanted the portrait to be serious, to reflect the gravity of the topic. But she meditated on McClain's smile as she worked.

"It was nice to be able to draw and just think of that."

Elisa Faye Rodriguez-Vila has heard some version of McClain's story before.

What helped her see past the pattern, to the person, were the words he spoke as officers pinned him down.

"It's kind of a small portrait of who he was," said Rodriguez-Vila, who lives in Miami. "You felt like you knew him just by hearing those words. You just see such a beautiful person coming through."

Rodriguez-Vila created an image of McClain's face out of the last words he spoke. As she worked, she said she entered a meditative state; the words kept reverberating in her head. The process reminded her of writing something over and over again as a punishment in school until the message was ingrained in your mind.

"It kind of felt like the world had wronged Elijah," she said. "And we have to repeat those words to ourselves, to not forget, to honor them, to have them ingrained in your mind."

She chose to put the words "YOU ARE BEAUTIFUL" and "I LOVE YOU" in capital letters on McClain's lips, because how incredible, she thought, that even in his final moments, he used his voice to spread love. She also felt that by placing those words so prominently, she was saying them back to him: "I love you. You are beautiful."

Sometimes Rodriguez-Vila feels helpless, especially in lock-down. How much can a doodle accomplish, she often wonders. But there's a quote she loves by the philosopher Herbert Marcuse: "Art cannot change the world, but it can contribute to changing the consciousness and drives of the men and women who could change the world."

Every Sunday, Nikkolas Smith sketches on his tablet at home in L.A. It started off as a therapeutic thing, a soothing outlet. Then, Smith started creating tributes to victims of racist-fueled violence.

"A lot of times, I don't know how to process all of the emotions just by myself," he said. "A lot of times, I need to create something, some sort of artistic tribute."

These days, Smith's Sunday sketches are even more therapeutic. He said they make him feel as though he's paying tribute to a person's life. He hopes his art can show the world that these lives mattered.

Smith has built up an Instagram following of almost 150,000. His tributes have reached a massive audience, and he said people like Michelle Obama have shared some of them.

He said people have reached out over social media to tell him that his pieces have been therapeutic for them, too, a way to process the horror of things they'd seen on the news and on social media, a way to grieve and to experience a moment of joy.

Smith's art has always been informed by a quote by Nina Simone: "An artist's duty, as far as I'm concerned, is to reflect the times." An artist has a responsibility, Smith believes, to hold a mirror to society. Art has the power to instantly impress on a person what is wrong and what needs to be done to remedy it. Smith creates art in hopes of inspiring people to make change.

Smith saw parallels between McClain's life and his own. He'd grown up Black in a predominantly white suburb in Houston. He, like McClain, is an introvert and an artist.

"I could definitely see myself being in the position that Elijah was in," he said. "There were times where I was just walking home, minding my own business as normal people do. And that shouldn't come with any sort of death sentence."

He found it difficult to sketch something for McClain. But his wife kept telling him he had to do something. And a voice in his head kept telling him he had to do something.

"But sometimes it's just...it's too heavy," Smith said. "It's too frustrating." It was days before he was ready to get to work.

Smith's style is deliberately unfinished, which takes on a new meaning with his memorial sketches, since his subject's lives were also unfinished.

He wanted to focus on who McClain was. He focused on his face, the violin, the cats. He wanted to create a warmth and glow around him.

Smith said he felt a bit more at peace after he finished McClain's portrait. He hopes he captured the essence of who McClain was and that it's a fitting tribute to his life. He hopes people will look at it and remember an amazing young man. He hopes they'll remember the reason McClain isn't around anymore.

"There were a lot of monstrous people involved in his murder," he said. "And they need to be held accountable. "

Celeste Byers lives in San Diego, about twenty minutes from the U.S.-Mexico border. One morning last spring, she learned about an immigration detention center in Otay Mesa, an area just north of the border. She hadn't realized that there were children imprisoned mere miles from where she lived.

"I felt so helpless," she said. "Like, what are we supposed to do? There's all these problems in the world."

Later that same day, she learned about McClain. She'd come across his face before on Instagram -- always the same image, shared over and over. But it wasn't until that day, when she came across a cartoon that told his story, that she registered who he was.

She started researching him.

"I had never cried because of a stranger's story before," she said. "I actually sobbed when I started reading about him and learning his story."

Byers realized there was something she could do to help: She could create art and share it.

Her tribute was finished that same day. She wanted to capture McClain's sweetness, to create an uplifting, respectful, beautiful memorial to him. She wanted to show him looking happy, being his best self. The tribute was shared online more than any other piece of art she'd posted before. She hoped it would inspire people to read more about him and about police brutality in general.

In the spring, artist Lisa Lloyd watched what was happening in the U.S. from her home in England.

"I didn't really know what to do," she said. "Because, you know, I'm a white woman. I live here. But I thought I had to do something."

She thought about a field of flowers: how, walking through one, you might not notice an individual flower. But if you take time to stop and look, you'd see the beauty in each one, the details that goes into each petal. She thought about how much energy must go into making a single flower.

It was, Lloyd thought, like being a mother. She's a mother herself. She thought about the effort and love and depth that goes into raising one person: You get pregnant, and then you grow someone in your body for nine months, and then you raise them. She thought about how all of that could end in a second, as it did for McClain.

"As a mom, it's almost unbearable," she said. "There aren't any words, from a mother's perspective. There aren't any words for it."

She decided she would pay tribute to victims of racial violence by creating small paper flowers. Each flower would be unique, representing a different individual who had died because of the color of their skin. She hopes viewers will see the particular beauty of each one and engage with the souls of each individual they represent.

She told me that her flowers don't only represent people who died in the U.S., but people from the United Kingdom, too, and elsewhere around the world.

"This problem exists everywhere," she said.

She's now several flowers into the project. Each is about four centimetres in length, delicately folded out of black paper. She chose the color to create a sense of gravity and power. The stamens are gold, she explained, to capture the essence of the person the flower represents. The final product will be a field of about 50 flowers.

"I'm hoping that will have a real impact," she said, "when you see that and you think each one of those is someone's life."

With McClain's flower, Lloyd tried to capture his energy, or at least what she could discern from reading about him. She wanted to show his creativity and lust for life.

"It's just incredibly heartbreaking, isn't it, that he spent his time trying to do good, and he was trying to make a difference in the world," she said. "He was trying to put good energy out there. He clearly had empathy, clearly sensitive."

Lloyd hopes her flowers start a conversation. She's reading a book by Brené Brown called "Daring Greatly." According to the book, some things need to be perfect. The internet, for instance, or a plane, must be perfect in order to work properly. Human beings do not, which is why art resonates.

"That's why we need it," Lloyd said. "We need music, we need songs, we need poetry, we need art, so that we can connect with other people."

Ameya Okamoto's hometown of Portland, Ore., has made headlines recently for ongoing protests over racial injustice, but she's been fighting it for years. She started volunteering with Don't Shoot Portland five years ago, when she was 15, working directly with families that have been impacted by racial violence.

Okamoto calls herself an "artistic first responder." She creates memorial portraits of racial violence victims and shares them on social media, turning them out into the world in a quick, accessible, shareable way. She wants to make sure she spreads their stories quickly to keep up the momentum of the movement, but wants to balance that with illustrating the complexity of who they were as individuals, maintaining their personhood rather than reducing them to a hashtag. To achieve that, she does a lot of research.

The more research Okamoto did on McClain, the more heartbroken she felt. She was struck by his sensitivity, the way he gave back through his music and moved in the world. It upset her to think about how young he was -- just a couple of years older than herself. She felt like she could relate to him as a 20 year old, an age where she's still figuring her life out.

"As young people, we're all figuring out who we want to be and who we are, and rapidly and chaotically and frustratingly," she said. "I have no idea what the hell I'm going to do or what I'm doing. And it breaks my heart that a lot of people aren't able to explore the end of their stories."

With her portrait of McClain, Okamoto wanted to capture who he was, but also to incorporate Aurora, believing that the places where we grow up say a lot about who we are. She placed mountains in the background, as well as silhouettes of string musicians raising their bows to the sky.

"I was really inspired by the rallying cry that these candlelight string vigils inspired," she said. It felt to her as if McClain was leading a revolution with his music. "Even if they're tiny revolutions in people's hearts and minds."

When Desmond Hansen heard McClain's story, he immediately wanted to paint.

McClain struck Hansen as an introvert, not unlike the friends he had growing up, who'd read comic books and stick to themselves. And not unlike Hansen himself.

He chose to paint on an electric box in his hometown of Seattle because it was surrounded by cement. If people wanted to create a memorial or a shrine out of it, they'd have room to leave flowers or stop and mourn.

Hansen wanted to give people something nice to look at. He wanted it to give them a warm feeling. He wanted to tell people that they shouldn't judge anyone, that we should just let people be and treat each other with kindness and love. He also hoped that the painting would remind viewers that some people are constantly targeted by the police.

"Seeing how the police treated him puts a lot into perspective for me," Hansen said. "It always is hard to take, seeing police bully people and brutalize people...beating someone and choking someone...and in the name of what? Them trying to leave or de-escalate a situation?"

Hansen said the level of violence inflicted on McClain and other police violence victims is something an average person would get prison time for. "It just makes no sense."

McClain isn't the first victim of police violence that Hansen has painted. He did a box painting of George Floyd, and placed it as close as possible to a police station -- about 80 feet, he said.

"That's just for a reminder that when they leave and hop in their car to go conduct their business, to treat people with compassion," Hansen said. "Because that kind of stuff doesn't have to happen."

Niki Croom of Columbia, S.C., couldn't believe McClain's story when she heard it.

"The more you find out, the more this whole situation doesn't seem real," she said. "Because how could that happen to such a beautiful, caring person?"

She recalled seeing a video of McClain that's gone viral since the news of his death broke. In it, he enters a room with a big smile on his face. Croom got the sense that he lit up that entire room.

"I felt like I knew him," she said. "Which is kind of silly, but I felt like I somehow knew him, just because his smile was so genuine. "

It felt to her like he didn't have any walls up, that he had an open heart. When she learned more about him, about his love for the violin and for animals, it impressed on her how much happiness he got out of giving, and how beautiful that was.

Croom felt a sense of responsibility to share McClain's story.

"I felt like I had some type of platform where if I said something, maybe people would listen," she said.

For her tribute, Croom decided to create a romantic nighttime scene. She wanted to place McClain somewhere magical.

"He deserves that," she said.

She painted him playing his violin surrounded by alley cats. She liked the idea of the magic of his playing drawing in those lost cats -- lost souls, she said.

"I was really hoping that people would fall in love with just the painting at first," she said. "And then they would recognize the man. That they would recognize that he's even more beautiful."

Elijah McClain reminded Leah Abucayan of people she knew in art school. They were artists. They were different. And McClain reminded her of herself.

"As an artist, I kind of do my own thing," she said.

Being different isn't something that should spark suspicion, added Abucayan, who lives in Atlanta. "Like, it's not weird. It's not crazy."

She wanted to create a lighthearted piece to capture McClain's sweetness and to get people's attention in a lighthearted way. She hoped that by looking at a soft, pleasant image, they might be more inclined to spend time with it, to learn from it.

After she posted her tribute, a light projection group in New York called Projection in Protest reached out to her. They asked if they could include it in a light show they were putting on in New York City during a violin vigil to be held in McClain's honor.

Abucayan's portrait of McClain was blown up to a massive size. That image, along with dozens of others, lit up the Washington Square Arch.

View the show in the video below:

Mica Angela Hendricks has been creating long, thin portraits on watercolor paper for a while, but lately she's been using her art to relearn history and to help other white people do the same.

She started creating portraits of Black historical figures to share their stories. She's a visual person and understands stories better if they're told in images, she said. She thinks that if history had been taught to her using images rather than words, she might have understood it better. She hopes her art might help others understand history better, too.

When the protests started, Hendricks was stuck at home, near an Army base in Fort Leonard Wood, MO. She's immuno-compromised and couldn't join in. She does, however, have a pretty big Instagram following.

She knew some people were tired of hearing stories like McClain's and dismiss them as infrequent occurrences.

"I think more of the white community needs to notice this," she said. "This is happening all the time. There's no reason anything like that should have happened to him. And I don't think it would have happened if he wasn't a person of color. "

She doesn't want to be, and doesn't see herself as, a spokesperson of the movement. What she can do, she said, is elevate the stories of people of color through her art, stories that Black people had been trying to tell for years but that white people have ignored.

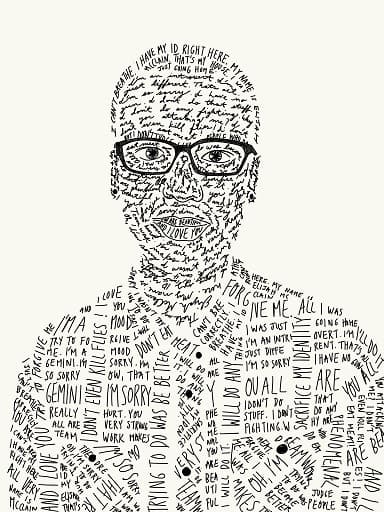

Vince Ballentine, a muralist in New York City, knew as soon as he heard McClain's story that he wanted to create a piece.

"It was kind of crushing because it was like, I know that dude," Ballentine said. "I know that guy. He comes in so many different names, in so many different places, but I know him."

He knew young men like McClain. He'd taught mural-based art classes to young people for years. These were kids who, like McClain, were artistic, and who had wanted to learn more about art. So when Ballentine heard McClain's last words, he thought any of his students could have spoken them.

"They can be a little introverted," he said. "They're very creative in their own right. And a lot of them express themselves differently. These kids are kind of considered outcasts sometimes. They're not the squeaky wheel, so people don't always pay attention to them. And they kind of like that sometimes. It's like they exist in their own way."

They remind Ballentine of himself. Ballentine saw a younger version of himself in McClain, too, and saw in him the friends he grew up with.

He now works to impart his wisdom and his experience on others who look like him. He said he didn't have that kind of mentoring growing up and didn't have a Black art teacher until he reached college.

Ballentine doesn't usually do memorial pieces. He worries that sometimes, people create memorial art without actively supporting the agenda, that some artists co-opt the movement or gentrify it.

"I just feel like if it's done haphazardly, it's gonna come across as just so wrong," he said. He wants to make sure that for any memorial piece he does, he puts in the work on that person and learns their story.

And McClain's story hit him deep. Especially his last words.

"The words. You read the words. Oh my god, it was just...that was the most heartbreaking thing for me," he said. "Because I couldn't get past the point of the true savagery in it. This person is talking to you with a clear mind, and they're young and defenseless, and this is what you're doing to him...why?"

He painted McClain's mural in Manhattan using a technique called scribble grid. In scribble gridding, words or scribbles serve as the background of a main image. For his McClain piece, the scribbles he used were the very words that had moved Ballentine so much.

Usually with scribble gridding, after the foreground is complete, the scribbles are painted over so all that remains is the main image. But Ballentine knew he had to leave the words. He felt that they were just as important as showing McClain playing the violin -- that together, they presented him as a complex human being.

"I think a lot of times, people aren't seen as complex human beings. They're kind of put into a box," Ballentine said. "This is who they are, and you're one of them, you know, and it becomes us versus them."

He also worried that McClain would be seen as just "another one": another victim of police violence, another Black man dead. He didn't want McClain to become a symbol of a string of tragic events, a drop in the bucket. He wanted him to be seen as an individual with whom people might identify and empathize.

He got to see that happen in real time as he painted the mural. People would stop by to watch Ballentine work. Sometimes, they wouldn't know McClain's story. They'd read the words and ask Ballentine what they meant. Sometimes passersby did know his story but not his last words. They'd often become emotional.

When the piece was done, Ballentine felt like he could breathe a sigh of relief. After months of wanting to paint the memorial, it was finished. He was relieved that it honored McClain specifically.

"Because I think those type of people never get praise," he said. "Nobody praises the introverts. Nobody praises the people that aren't the loudest in the room. They kind of fall by the wayside."