Alexander Landau doesn't hesitate to explain in front of his 6-year-old daughter what it felt like when a Denver police officer held a gun to his temple 11 years ago. He wants Maya to know America's policing system treats people who look like him unfairly.

"I remember the pressure from the barrel, the cold steel, and I could even see his hand gripping the handle and his finger on the trigger," Landau said. "And I just closed my eyes and expected to be shot."

Around 12:30 a.m. on January 15, 2009, Denver police officers pulled over the then-19-year-old for an alleged illegal left turn. The officers began beating Landau, who is Black, with fists, a radio and a flashlight after he asked for a warrant for the search they performed on his car. Landau said officers Randy Murr, Ricky Nixon and Tiffany Middleton bloodied and bruised his face nearly beyond recognition. His brain was injured. And after one of the officers called Landau the N-word, he was full of rage.

Landau called his experience just one episode in a 400-year-old American tale in which white authority figures regularly persecute Black people, sometimes violently, over the color of their skin. He calls his beating a symptom of a larger sickness plaguing society that's reflected in local police departments in Colorado and across the country.

"You have to understand the history of what this institution is," said Ana Ortega, another victim of violence perpetrated by Denver police officers in 2009. "You have to understand the creation of this. Reform doesn't work because (the system) is not broken. The system is working exactly the way it's supposed to."

Landau and Ortega rolled their experiences into the Denver Justice Project, a nonprofit that aims to abolish racism from the criminal justice system. Their organization, which worked on the sweeping police reform law that passed the Colorado legislature this year, joined the chorus of protesters demanding change in police departments following George Floyd's death.

"My life is just as important as any one of those officers' lives. But the difference is I can't behave the same way," Landau said. "I'm not going to allow officers in my community to continue to do things like they did to me if I can prevent it."

When protesters took to Capitol Hill and downtown this summer, their list of demands didn't end at things like equity training and cultural competency seminars. Many called for an end to policing altogether. They argued radical change, not piecemeal reforms, are necessary because Denver's historic lack of accountability -- and lack of investment in alternatives to traditional policing -- has made the current law enforcement system untenable.

People like Landau and Ortega, lawmakers and top law enforcement officials all argue policing in Denver must change. Their ideas for reform may differ, but they acknowledge the status quo simply doesn't work. And there are receipts.

Over the last 10 years, policing and jailing people in Denver has accounted for almost a third of the city's budget. But hefty spending and more cops on the street haven't necessarily resulted in a safer city.

The Denver Police Department is the costliest part of the Department of Safety, which usually ranks as the most expensive city agency. And spending on law enforcement continues to rise, budget documents show. Last year, taxpayers spent over $268 million on policing compared to $179 million in 2009. To jail people, Denver spent over $156 million last year compared to $94 million 10 years prior. As of June 15, DPD counted 1,586 sworn officers, 140 more than in 2009.

But a bulkier blue line and an increase in spending has not equated to less crime. Violent crime -- things like murder, rape and robbery -- has risen almost annually since 2009, according to the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which DPD uses to track crime. The city saw a slight dip in 2010 and 2018, and DPD attributes a big jump in all types of crime between 2013 and 2014 to a change in how officers collect data. This year is on track to be one of the city's most violent in recent memory.

Many of the officials Denverite spoke to for this story cited population growth as a reason for the rise in crime. But crime per capita has remained essentially steady.

Lisa Calderón, a criminal justice professor at Regis University and chief of staff for Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca, said she isn't surprised.

"I think we need to first stop using the number of police as a measure of whether there's a reduction or increase in crime. We have to first look at what are the drivers of crime," said Calderón, who ran for mayor last year and oversaw the Community Reentry Project for a decade.

She cited domestic violence as an example. When she served as legal director of an abused-women's program, Calderón said she realized family instability caused by rising housing costs and job loss could lead to more violence at home.

"That's not to excuse abuse," she said. "It's to understand how people are interacting and resolving problems when left to their own devices but without enough social supports to deal with them. So what we've been relying on is the police as a mechanism for those social supports, and that's where it's failing."

Murphy Robinson, who Mayor Michael Hancock picked to lead the Department of Safety this year, has committed to transforming the police department. But reducing the force isn't his goal.

"I think we can help set a new precedent for what policing looks like in the country ... but it does not negate the fact that the job of a police officer is important and is valuable and is necessary," Robinson said.

Since being sworn in two years ago, Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen has supported the need for more progressive reforms of the department.

He pointed to how the department has changed its approach to nonviolent crimes -- things like drug possession, public drunkenness, property damage and stealing from cars. It may be small-time stuff, but those charges can result in jail time, which can result in job insecurity, which can result in home insecurity, which can result in a higher recidivism rate.

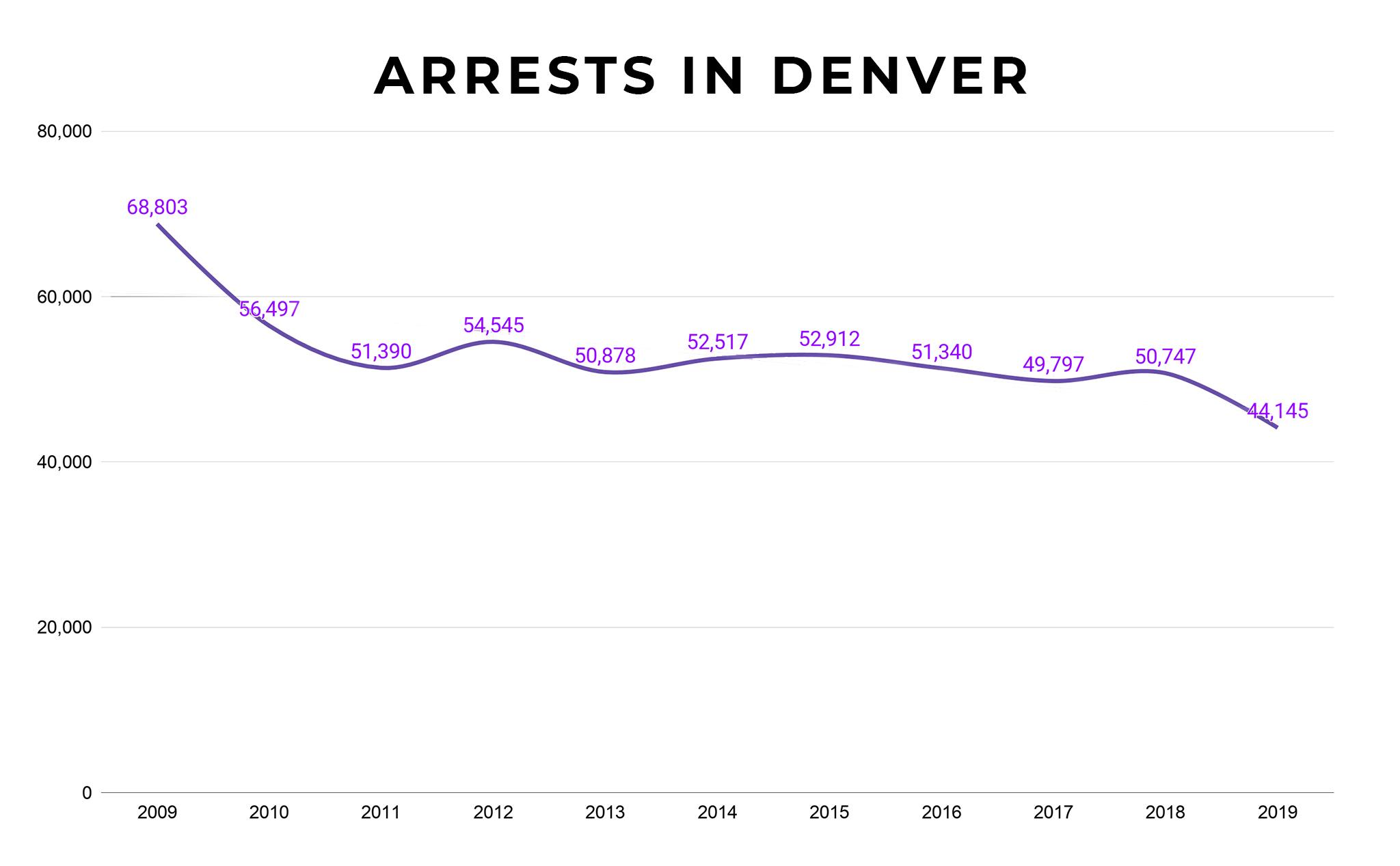

After an anomalous jump in 2014, the city has averaged about 50,000 nonviolent offenses a year. Denver dipped below that average in 2019 despite more people living here. That year, officers made far fewer arrests than any year over the past decade, according to Department of Finance records.

Source: City and County of Denver

Pazen attributes that change to new programs, such as the city's "co-responders" initiative, that divert low-level offenders away from jails and courts and toward social services. In 2016, police began partnering with the Mental Health Center of Denver when responding to certain emergencies. By 2018, the so-called co-responders gave 95 percent of the people they encountered an option that wasn't jail. The number of interactions was small -- around 1,700 in a city where officers make about 50,000 arrests a year -- and the co-responder force is tiny compared to the police department, with just 17 social workers who partner with cops. But Pazen said he will "build on those successes."

Another progressive program touted by Pazen and his boss's boss, Hancock, removes armed officers from some 911 calls entirely. The Support Team Assisted Response program, or STAR, reroutes some 911 calls to mental health professionals and a paramedic. Many of the encounters involve unhoused residents who might be dealing with substance abuse, suicidal thoughts, or any number of problems that could use compassion instead of cuffs.

Denver's top officials may tout law enforcement reform, but nothing reflects what the city cares about more than its budget. And over the last ten years, that document reveals a police department that's outfitted mostly for traditional policing.

"We have what we've funded. I mean, it didn't just happen," said Christie Donner, executive director of the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition. "Budgets build realities. It speaks volumes, whether intentionally or unintentionally, about your values."

Some of the city's most radical criminal justice advocates applaud the co-responder and STAR programs. But the amount of money spent on these and other diversion programs is minuscule compared to the money spent on traditional policing. In August, the co-responding initiative received its largest annual grant yet -- $1.2 million. The other program, STAR, is based on a program in Eugene, Oregon, that's 30 years old. Denver's program is a six-month, grant-funded pilot with an uncertain future.

City budgets show diversion dollars almost always come from grants, meaning they're not guaranteed to last. Over the last 10 years, budget documents show that the city's criminal justice system has utilized a few dozen grants for various diversion programs. None of that spending comes close to the hundreds of millions of dollars invested in the gun-and-badge approach.

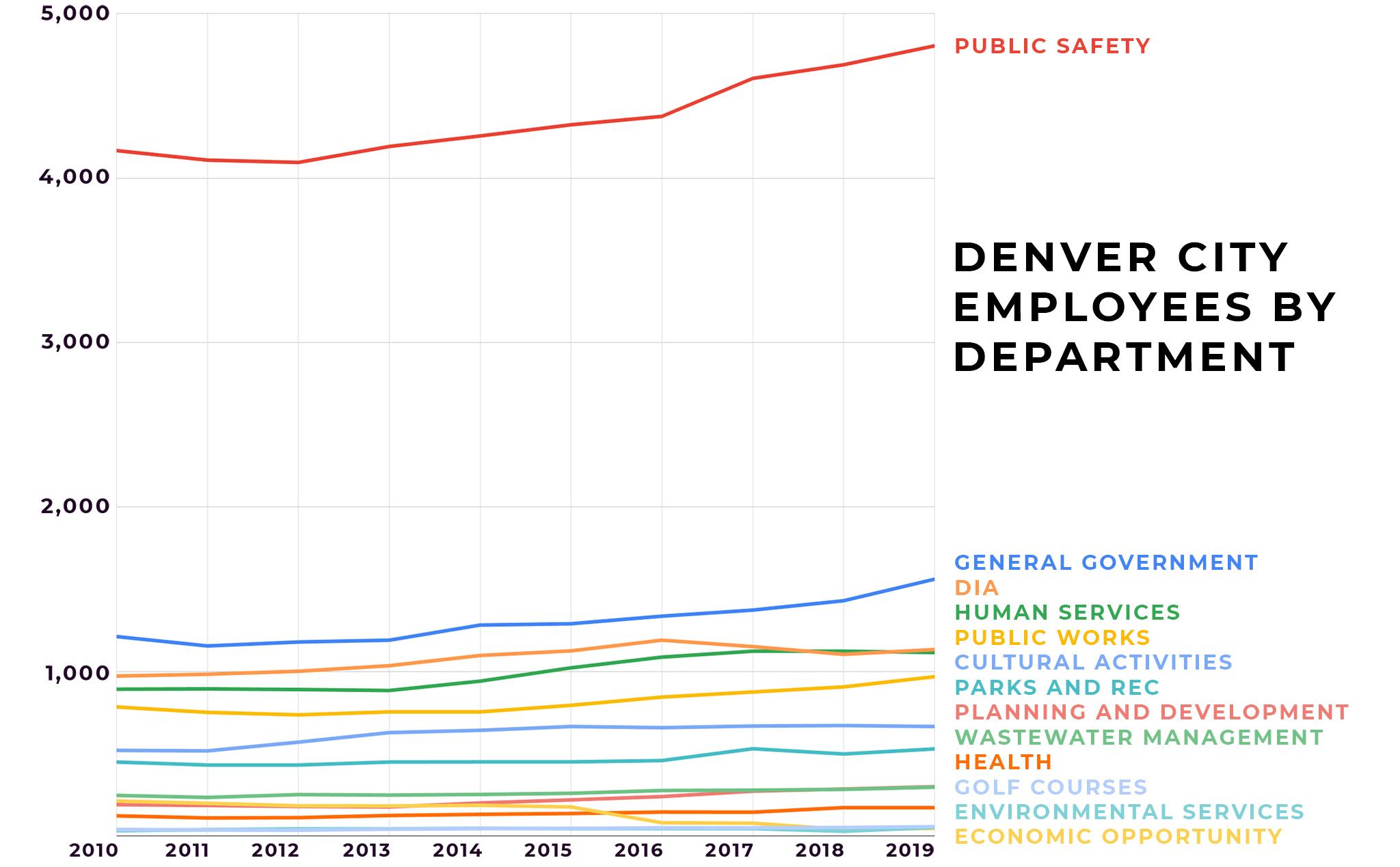

In fact, the Department of Safety, which includes the police, sheriff and fire departments plus 911 communications and special initiatives for children and gangs, trumps every other city department in terms of budget and workers. Spending reports for 2019 show the safety department counts more employees than the human services, health, environment, economic opportunity, parks and recreation, airport, and general government departments combined.

Here's how the city's spending has broken down against other priorities over the last decade. (The vast majority of human services money comes from state and federal sources):

Public police budget hearings in front of the Denver City Council begin Sept. 18. DPD's budget will likely dwindle because of the economic disaster caused by COVID-19. Meanwhile, the Hancock administration is negotiating a new contract with the police union that includes a raise for officers in 2022.

Indeed, Hancock sets the budget every year, and the city council approves it. The mayor has increased DPD's force numbers every year since 2014, budget documents show. While Hancock takes credit for the expansion, he said voters and city council members gave him the mandate to add officers as well as increase accountability.

"The reality is that the majority of the people recognize the value of ... good policing in our communities," Hancock said.

Hancock blames rising crime in Denver on forces he says are out of his control, such as meth and opioid addiction, an influx of guns, problems with the educational system and unequal access to healthcare. He says he hears protesters and understands "the sense of urgency to go faster and to do more" to treat the societal causes of crime.

But he does not necessarily support defunding his police department in order to reform it. He can find money for more empathetic approaches to crime elsewhere in the general fund, he told Denverite.

"These are very complex societal conversations that need to occur, including (police) excessive force, for us to do it right," Hancock said. "And if we're truly interested in having effective responses to the questions, concerns and challenges facing all of us today, you cannot reduce them to some quick answers and quick hashtags right now. And that's what my job is, as I see it, as mayor: to be thoughtful, smart and thorough if we're gonna do it at all."

Hancock admits to a combination of "a few bad actors" and, before his tenure, "decades of very bad decisions and development of a culture that has allowed for a lack of accountability."

But Donner argues the city cannot maintain DPD's funding levels and simultaneously institute meaningful reforms. She's a fan of the co-responder program but said the depth of "community-based responses" favored by her and other reformers would invalidate massive police forces and much of the jails and courts that support them.

A Denver Post analysis recently found that DPD officers spent 80 percent of their time on things other than violent crime, such as domestic disputes and noise complaints.

"Even though we recognize that we're overusing the criminal justice system from a funding perspective, we keep driving the money into a system to do something different," Donner said. "And some of that might be appropriate. But what Denver has never done ... is actually fund the alternative to the criminal justice system response instead of asking the criminal justice system to respond differently. And those are two very, very different things."

Denver Police Sergeant Brian Conover represents one system tasked with responding differently. He's in charge of the city's homeless outreach team, an eight-person group of officers whose beat revolves around helping the unhoused. "It would be amazing" if his budget could triple in size to hire more co-responders, he said.

Conover says he joined the force to help people. While he understands some of the anger aimed at police officers, he says he doesn't let his gun and badge define his role.

"We're human and not just a uniform," he said. "We don't have PhDs in psychology or counseling or mental health, that's for sure. However, the department has provided us a lot of specialized training, not just my team, but the whole department. It doesn't make us necessarily experts, but it makes us much better at what we do."

In an interview, Hancock touted a handful of law enforcement reforms he's overseen since taking office. In his first term, he fired Police Chief Gerry Whitman, who was in charge during a slew of brutality cases, including Landau's and Ortega's, and replaced him with an outsider that the mayor said addressed cultural problems. Hancock directed chief Robert White to strengthen discipline for officers, and he reduced salaries for DPD brass to put more boots on the street.

The mayor also oversaw the construction of Denver's use-of-force policy after advocates demanded it. And, after police shot and killed 17-year-old Jessica Hernandez in 2015, Hancock banned his officers from shooting at moving cars unless being shot at.

Donner recalled another early priority of Hancock's: a $378 million jail-and-courthouse combo approved by voters in 2005 and supported by the councilman who would become mayor. The project perpetuated the demand for policing and jailing, Donner said.

"This is not a new conversation," she said. "We were saying the exact same thing the community is saying now, which is we are putting resources in the wrong place. We're not solving problems, and we're not making communities safer."

Hancock's priorities seem to have changed since then. Now, Denver's pricey jails sit half-empty with his blessing. And he supported the Caring 4 Denver initiative to fund solutions to mental illness.

Still, Donner and others argue that policing is just one part of the problem. They say the criminal justice system as a whole needs to be overhauled.

The court system sees a disproportionate number of unhoused residents and people of color, according to a study from the city public defender's office.

About 38 percent of cases in Denver's municipal court stem from issues related to homelessness and low-level offenses like sleeping in a park after hours and drinking in public, the study found. A disproportionate number of people arrested are Black. And about 70 percent of the low-level cases involving unhoused people get dismissed.

"Some of the people who were arrested would have benefited more from things like housing and mental health help," said Nathaniel Baca, an attorney who works for the city's public defender office and who worked on the study.

"They have to go through a number of hoops only to arrive six months or a year later where the case is going to get dismissed," Baca said while testifying in front of city council in August. "So we think this is a fairly substantial problem, especially given this population."

Fewer interactions between police officers and the public would do wonders to break that cycle, said Dr. Robert Davis, vice president for the Greater Metro Denver Ministerial Alliance.

Davis is co-leading the creation of a community task force that will eventually recommend reforms to DPD. He declined to offer specific policy recommendations because the process is not finished. But he said the department should generally work to minimize its contact with the public.

"I think about it from the perspective of the fire department," Davis said. "Our goal, relative to the fire department, is to minimize the amount of times that the fire department is called. That's why everybody has smoke detectors in their home and we require certain codes and stuff around what we are doing because we said we don't want firefighters having to come to people's houses."

But Hancock doesn't think shrinking the department itself will change policing.

"The reality is that more people will be standing and saying, yes, we need police in our community, but we want accountable police departments," he said. "We want smart responses to the needs and the challenges of our communities."

Does the city feel safer with DPD around? That depends on whom you ask.

Spending numbers can tell us certain things, but not all things.

"It's just from an academic perspective incredibly challenging to say that because we spent X, we saw Y change," said Richard Auxier, a senior policy associate with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center. "The best way you can do this is to interact with the community members, ask questions. Do they feel safe? Is the economy growing, and is that economic growth equitable? Are all different types of people and different races feeling the same way about the police presence?"

A new survey shows plenty of Denverites see police officers as instigators rather than protectors. More than half of the 334 people surveyed by the coalition to reimagine DPD cited "over-policing" and "over-criminalization" as the department's most problematic trend. Systemic racial discrimination and the use of force were the other top concerns.

Those concerns are founded in data. Denver's taxpayers continue to foot the bill for claims of civil rights violations committed by law enforcement. The city has paid over $18.4 million to residents and their estates over the last 10 years to settle such claims and judgments, according to the City Attorney's Office. Police officers used violence before, during or after arrests around 3 percent of the time last year, according to DPD data. And DPD and the Office of the Independent Monitor are reviewing hundreds of use-of-force complaints submitted after violent protests this summer. While officers completed one eight-hour session on Denver's use-of-force policy in 2018, a comprehensive, two-day training was interrupted by the pandemic. During the height of protests this spring, 89 percent of the police force had yet to take the course, a DPD spokesman said.

Ortega, who identifies as Latina, does not feel safe since officers beat her up and put her in jail. But she said she's never really felt safe. She grew up in Five Points, where she saw officers pull over her cousins weekly and question them because they looked like a suspect or were acting suspicious in the eyes of the officer, even if they were just idling in front of their grandmother's house.

She even felt uneasy standing up to authority in court while her trial played out.

"I was really afraid of the retaliation, it was something that made me really nervous for my family," Ortega said.

Landau said he can't trust police because of what they did to him. But he mostly blames the system that protects them.

Officer Nixon, back on the street in 2009 after beating up Landau earlier in the year, was moonlighting as a private security guard at the Denver Diner when he and other officers beat up Ortega. Nixon was eventually fired. Officer Murr, who beat up Landau and later Michael DeHerrara and Shawn Johnson, might be getting his job back -- with 10 years of back-pay. The Hancock administration is negotiating with Murr, Officer Denvin Sparks and their attorneys, a spokesman with the City Attorney's Office said. It's unclear if either would ever work the streets again.

"Had they been disciplined appropriately in my case, maybe the Denver Diner case and what happened to Sean and Michael would have never occurred and we'd have saved a lot of money. We'd have saved a lot of trauma," Landau said. "And we'd have started to really rebuild relationships between community and law enforcement."

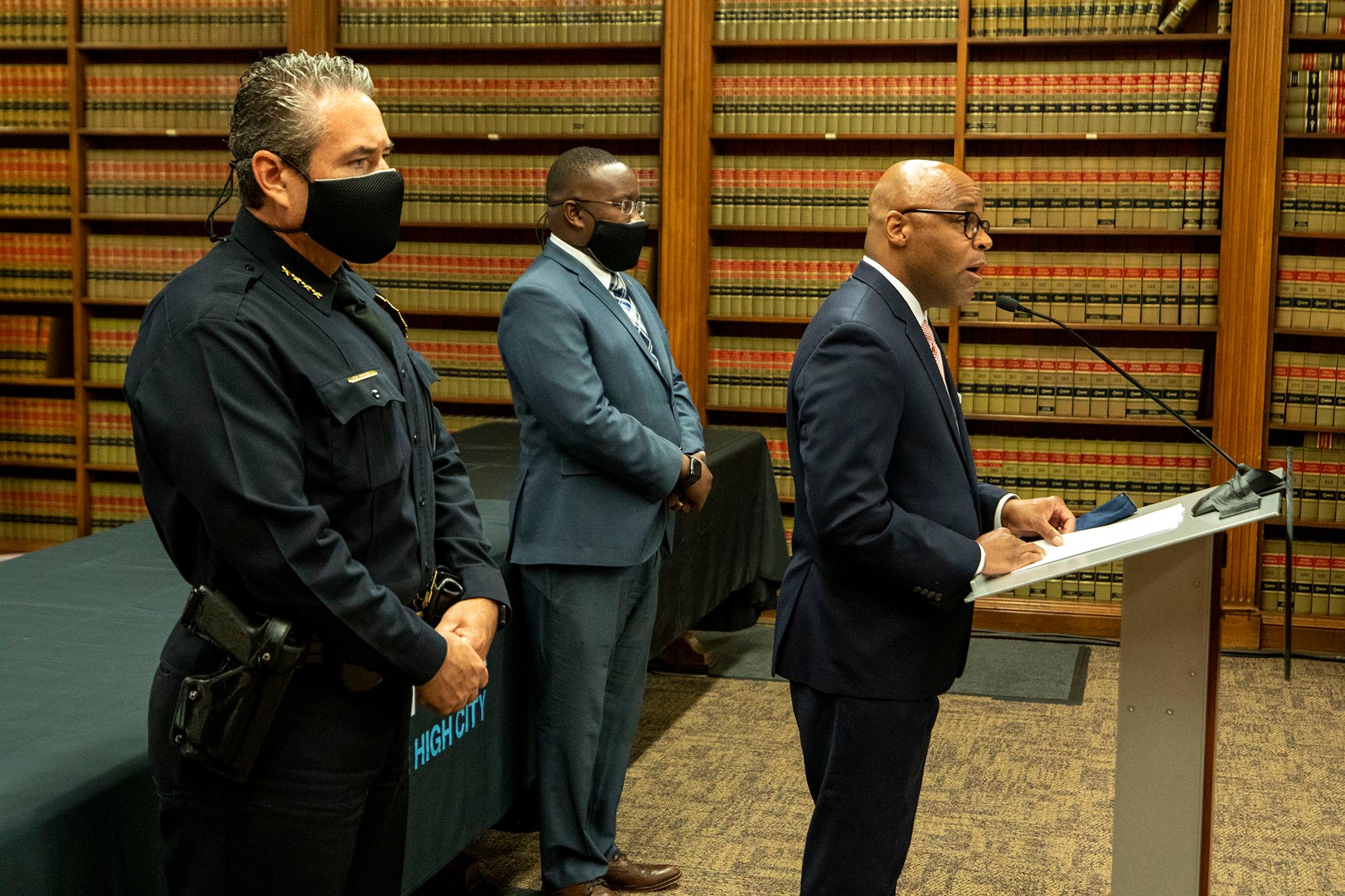

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Plenty of others have come out against the criminal justice system in recent months.

There's Ivette Mendez, sister to 16-year-old Alexis Mendez-Perez, who was shot and killed by off-duty Department of Corrections worker Desmond Manning while the teen ran through the man's backyard. Mendez told elected officials last month that she wanted justice for her little brother. District Attorney Beth McCann declined to charge Desmond.

There's Rosie DuPree, who recently told city council members that she learned "police kill children, too" in 2003 when a Denver officer shot and killed 15-year-old Paul Childs.

There's Michelle Harris, a Black resident who was marching for racial justice in May through downtown Denver. "How much more blood has to be shed from us?" she said through tears and shaky breath. "We've shed enough blood, and this country wouldn't be here if it wasn't for African-Americans."

In August, Chief Pazen and Mayor Hancock held a press conference at the city's crime lab after a mass shooting at a westside park happened in broad daylight. They said such violence would not be tolerated.

"We have to set those differences aside and work together because kids being shot in our streets is not OK," Pazen told Denverite after the event. "We need to be coming together to provide a more supportive network to those vulnerable populations while we are very precise in addressing the individuals that are creating harm.

"The folks that are shooters, we need to be more effective in taking shooters off the street and the folks that are dealing with substance abuse issues, getting them the support that they need," Pazen said.

Landau knows killers exist, and he knows cops can be a line of defense. He comes from a family of police officers. He knows cops are people who need jobs just like everyone else.

"In a nutshell, yes, we are an abolitionist organization," Landau said of the Denver Justice Project. "But we also understand that to immediately dissolve law enforcement without an effective and strategic and healthy replacement could potentially do the community far more harm than is currently been done and continues to be done against them with the existing police department."

The biggest attempt yet to abolish DPD failed. Sponsored by Councilwoman CdeBaca, an upstart politician elected in an upset to change the status quo, the initiative came directly from activists calling to abolish the department and spread the windfall to residents who CdeBaca said need help, not handcuffs. The proposed ballot measure failed after CdeBaca's colleagues on the council said they felt blindsided and worried it would make change harder to accomplish down the road if voters rejected it.

Landau was disappointed the proposal failed, but even he admitted that the city is not ready to rid itself of the department in one fell swoop. He believed CdeBaca's proposal conveyed the will of a lot of Denverites. He said people in power must value the expertise of the people who they're sworn to protect -- to look to them, instead of an institution with a legacy of problems, for answers.

"They need to recognize that the more community can take care of itself, the less need there is for law enforcement in those communities," he said. "And that's a tough pill to swallow if that means your job is over. Expertise is through experience. We know what's good for our communities. You just got to trust us."