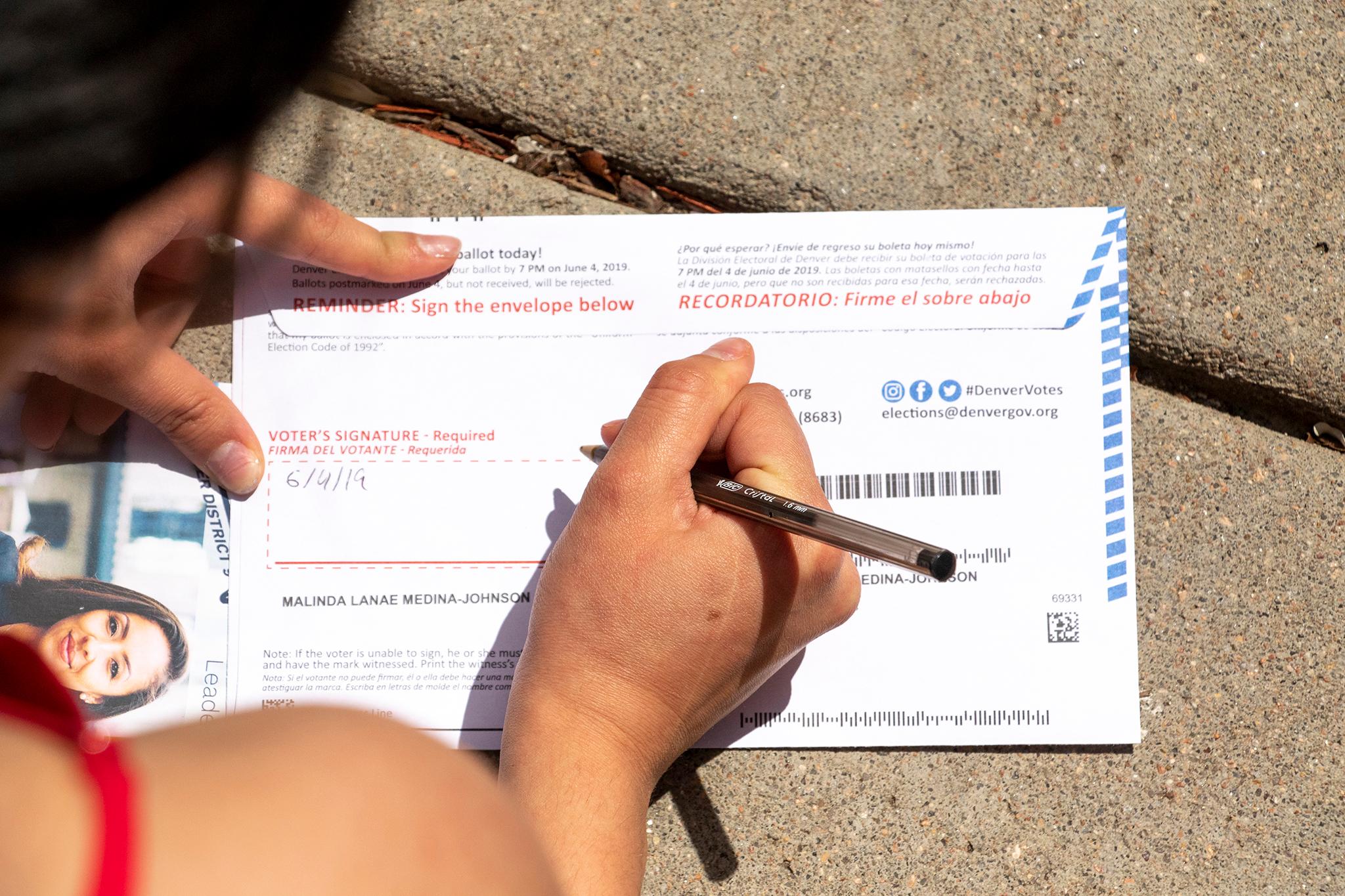

I tried to vote in the 2016 presidential election. I really did. But I later learned my vote wasn't counted. The culprit: my squirrely, terribly inconsistent handwriting. I can draw in Times New Roman, but my brain just stops working when it comes to a John Hancock.

Denver Elections rejected my signature. They followed their protocol and sent me a letter informing me that I messed up. That letter spelled out a number of ways that I could fix, or "cure," my ballot. But I didn't check my mail for days. By the time I found the note, it was too late. As a result, my voter form and personal info were likely sent to the Denver District Attorney's office to live in a dossier of discrepant ballots.

So when reader Lydia wrote in asking about signature pitfalls, especially if someone experiences a traumatic brain injury or if something happens to their hands that changes the way they sign their name, I felt a personal urge to figure out how this works. This is an explainer to help you avoid the mistakes I have made.

Lesson 1: Signature verification is all about history.

When you cast your ballot, be it in person, through the mail or into a dropbox, the envelope bearing your votes and signature enters a streamlined system at Denver Election headquarters at 14th Avenue and Bannock Street. There are big machines that parse them, then "adorable bipartisan teams" help verify each one.

The elections robots extract signatures and pull them into a computer system where humans try to match them with older signatures in the database. Everyone has at least one older signature in the database -- you needed to sign your name to register to vote in the first place.

Not everyone penning wildly varying signatures will be rejected. Stuart Clubb, ballot operations coordinator for Denver Elections, said the department's volunteer judges are trained to make matches. Voters who have a lot of elections under their belts also have a lot of signatures in the database, and Clubb said judges can often trace the evolution of their personal scrawls over time.

"If we have someone who has a long voting history, that's going to be better for us because we can see over the years how much a signature has changed," he said. "We're going to be a little bit more tolerant about how you're all over the place."

These things do change in predictable ways. Younger people tend to change their scribbles, he said, since they're still trying out new things and finding which pen strokes are right for them. As people age, their signed names tend to solidify into more consistent patterns.

Clubb blames this on adulting. As they get older, "people are starting to sign more important things."

But those younger folks, who are still in heydays of signature experimentation, are also likely to have fewer records for judges to compare with. If the signature on their ballot is too far afield from those found on their voter registration or DMV records, they'll get flagged.

So the lesson here is: Try to stay consistent between these official documents if you're concerned about getting a rejected ballot, especially if you're a new voter.

Clubb said those that get flagged enter stage one of analysis, when volunteer judges try to dig a little deeper and see if a signature matches anything else in their system. They might look closely at how you write specific letters. Maybe the voter just had a bad hand day.

If there's no reconciliation in "tier one," the ballot moves to another round of review. Sometimes, married couples accidentally switch envelopes and sign the wrong one. This is something judges catch in "tier two" reviews. In the case of the flip-flopped ballot, as long as both have been submitted, judges will catch the mistake and cure both ballots.

But Clubb said he tells judges not to worry too much if they feel they need to reject a ballot. For one thing, it's better to be safe than sorry. Making a voter cure their own ballot means they'll have to sign their name again, so signatures rejected because there are very few past examples will have a couple more examples in the system once they respond.

People who get a rejection letter need to send in a copy of their ID with a signed affidavit to make amends. They can mail this stuff in, handle it online and even text the info back to the city.

Getting back to Swize's question about injuries that may affect how people sign: Clubb said citizens can register to vote multiple times. That's one good way to get a new signature into the system.

"You can fill out as many registration forms as you like," he said.

And the signatures he's seen in his time at Elections have taken all forms.

"We get people who do a symbol. I've seen smiley faces," he said. Apparently that's fine, so long as you're consistent.

And if you really cannot sign your name, you can put a mark, like an "X," on the signature line if you have a witness sign in the appropriate box below. But if you put anything that looks like a signature in the voter signature box, law stipulates any witness information must be ignored, and your scrawl will be sent to verification.

Lesson 2: Sign up for Ballot Trace.

In addition to automated ballot machines, voters also can use an automated tracking system to make sure they have properly participated in democracy.

If you're signed up for Ballot Trace, you'll automatically get text or email alerts letting you know your ballot has been received, processed and counted.

I was not in the database in 2016, so I didn't get any notifications when the rejection letter was sent my way. If I had, I may not have allowed that crucial note to languish in my mailbox. Voters have up to eight days after election day to make this happen; I happened to vote right before election day.

Because I never responded, Clubb said, my discrepant ballot was sent to the Denver District Attorney. It's evidence now, in case I'm a fraudster they might need to build a case against.

It's the law, he said, to do this with ballots that have bad signatures and do not get cleared up. So there's more going on than a lost vote.

Clubb said there are occasionally cases where someone gets a letter about a bad signature and responds that they didn't write it. This is voter fraud caught before it could impact an election. He said less than one percent of ballots actually end up going to the DA's office. In 2016, that'd be less than 3,500 votes.

And clearly they're not all related to fraud. At least one was due to an irresponsible voter with terrible handwriting and a terrible relationship with his mailbox.