He had been sleeping in doorways for nearly a week when a friend invited him to spend a chilly night in a tent pitched steps from Coors Field.

Kenneth Wing was hesitant because he knew city workers were scheduled to clean the sidewalks in the area the following morning.

"Am I going to be dragged out by my feet, hosed down?" Wing asked his friend. Wing had never been through a cleanup before, though he has been without permanent housing in Denver, his hometown, since last year.

Dwight Seay assured Wing that that would not be the case. Cleanups, which Denver's Department of Transportation & Infrastructure says are necessary to maintain the public right of way, are disruptive and stressful for people experiencing homelessness, but not in the way Wing feared.

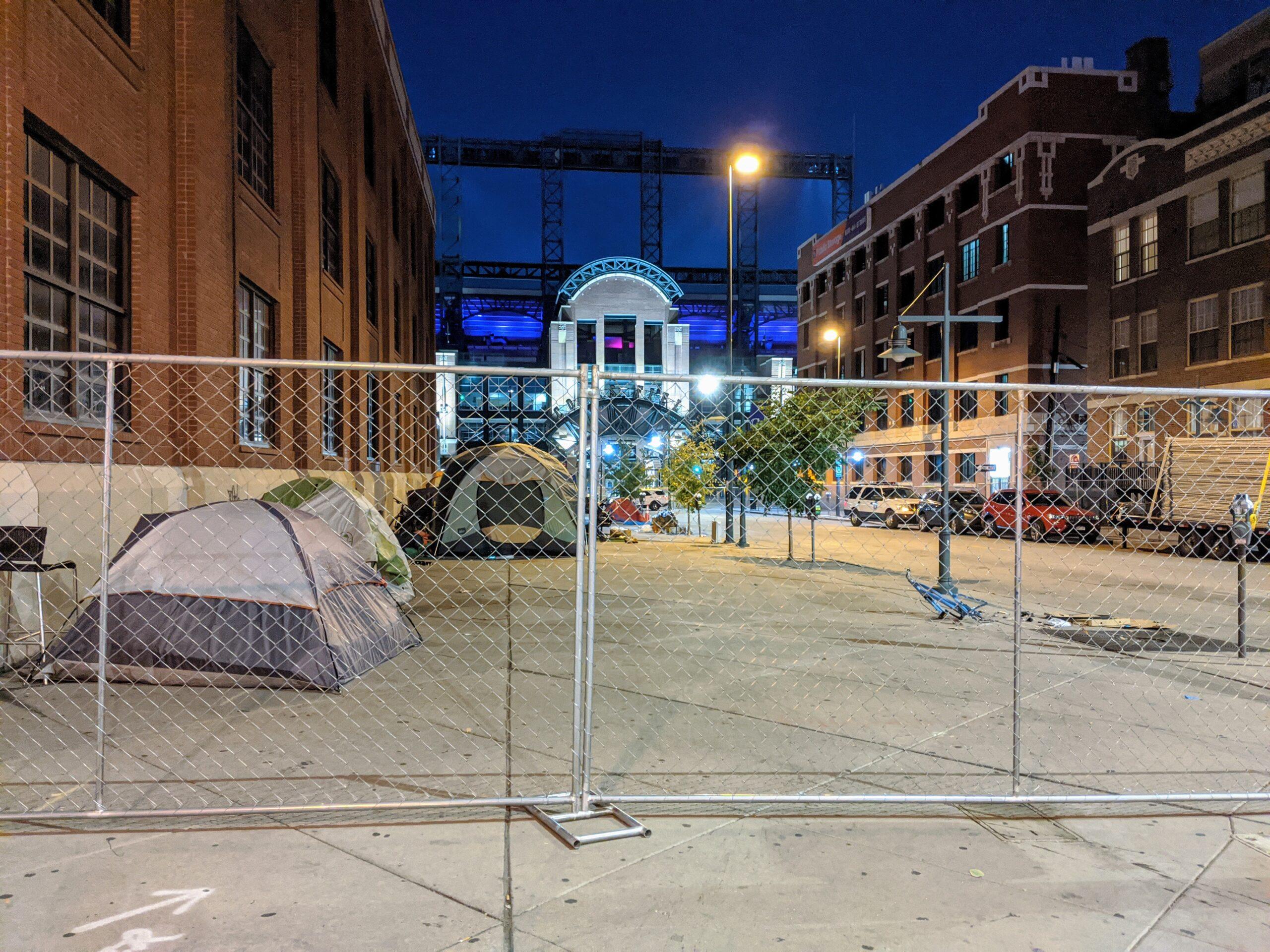

Seay knew from experience. A recent cleanup not far away had led Seay, known as Blessed to friends, to move his tent and other belongings to 21st Street just south of Blake Street. Seay set up on a patch of the sidewalk broad enough for the crowds of baseball fans who would have hung out awaiting the start of a game in seasons before the pandemic.

Another cleanup is scheduled Wednesday nearby, at 25th and Welton streets. Property owners have placed jagged rocks and giant metal planters in places where people experiencing homelessness had been living in tents before previous cleanups.

City workers collected more than two tons of waste in an Aug. 17 cleanup near the Denver Art Museum. In late August over two days around 22nd and Champa streets, more than 10 tons of waste was collected. On Sep. 22 nearly 4 tons was collected at 25th and Arapahoe streets. Hundreds of needles have been collected during cleanups.

Wing took Seay's offer to spend the night. So both men were there before dawn Tuesday when police cars blocked off surrounding streets and workers started erecting chain link fencing that they have been using lately to close off areas to be cleaned. After about an hour, police officers and social workers began calling to people in tents:

"Good morning. Denver police. You guys gotta be out of here in about an hour."

Vintage R&B, including Rose Royce's "Love don't live here anymore," played from speakers as Seay began bringing bags and other belongings from his tent, making a neat pile he topped with a teddy bear. He said the music helped him work. Wing helped Seay remove the poles from his tent.

Seay said he wasn't sure where he would spend the night, but he did know it would not be in a shelter because "that's where the coronavirus is."

"There's a lot of hate out here," Wing said, adding that crime and the potential for clashes with others kept him out of shelters and wary of encampments. He said he would spend Tuesday night "wherever I lay my head."

Seay's first concern was finding a place for his belongings. The city offers storage bins during such cleanups, but Seay said he needed more space.

"I'm taking everything," Seay said. "I'm not losing not a sock."

City housing officials and homelessness service providers are seeing encampments grow amid the economic slowdown created by the pandemic. Existing shelters have had to reduce beds to create the social distancing necessary to stop the spread of the coroanvirus. With winter approaching, Denver is preparing to open a new shelter in northeast Park Hill.

On Tuesday, a bulldozer scooped up tents, tarps, suitcases, even a patio umbrella that had sheltered someone who was absent when the clean-up began. Belongings seen as abandoned were loaded into a trash truck. Another truck carried green bins people could use for items they wanted taken to city storage areas.

Friends eventually helped Seay secure a private storage locker.

"Now I'm on my way to get myself situated," he said at midday.