There's something new happening in Five Points. The nondescript red-brick building at Washington Street and 24th Avenue is now home to a "virtual" gun range, what co-owner Wanda James says may be the first Black-owned shooting and training business in the city.

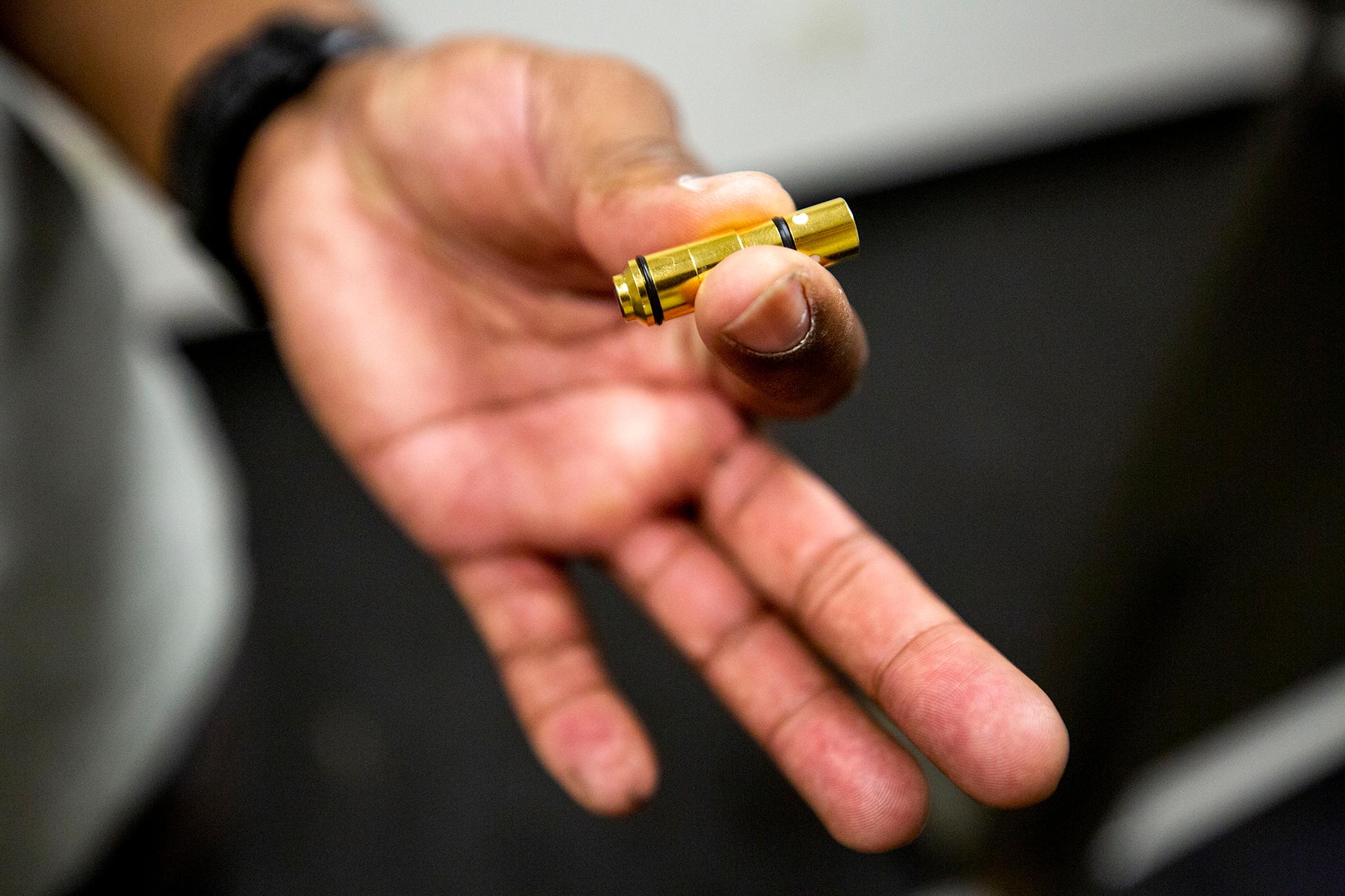

Traditional gun ranges, where people fire live rounds, aren't allowed in Denver. That's why 17 Seventy Armory and Gun Club uses lasers. Customers can bring their own firearms into the space, unloaded, and stick a fancy infrared cartridge into the chamber. A camera system picks up the shot, sometimes just for target practice and sometimes in interactive games. There's no recoil in dry fire like this, but instructors here say it's still important practice for people who haven't spent a lot of time with a finger on a trigger.

But the high-tech system is just one part of the new range. Training people how to use guns and, more importantly, how to avoid using them, is the bigger goal. In a tense moment for America, James said it's more important than ever that African Americans have access to this kind of education.

The world feels less safe, and guns and ammo are selling like hotcakes.

Last Saturday, 17 Seventy held its first concealed carry class. A projector glowed in the darkened room as instructors Anubis Heru and Master Young started with the basics. It was a small class, staying in line with the city's newest COVID-19 rules. All present were people of color.

Before they turned to ammo, caliber and how to hold a pistol, they stressed the responsibility that comes with owning a deadly weapon. How do you even register a threat?

Know how to hold your body. Keep your eyes and ears open. Be aware of what's around you.

"Pay attention," Heru told the group. "Pay attention but don't panic."

Safety starts long before someone might ever need a firearm. It's the key thing James hopes people learn here. It's relatively easy to buy a gun, but people don't automatically understand the laws or the weight that comes with a purchase.

"More than anything, I want them to be safe and confident and understand the responsibility," she said.

James was a Naval anti-submarine officer during the Cold War. She's been a gun owner for decades, and friends have long asked her for training. But in all her years dealing with guns, she said the country feels more volatile in 2020. Owning a firearm, and understanding that responsibility, somehow feels more necessary.

She pointed to the random murder of Isabella Thallas near Coors Field last June and the 2017 white nationalist demonstrations in Charlottesville.

"The world is just a different place right now," she said. "This is the first time in 30 years, since I left the military, that I have felt necessary to ensure that my husband and my family and I are protected in our home."

This is partially due to national politics, what James described as intense ideologies merging with cultures of weapons and violence. She's had a fair share of charged language directed toward her on social media. Even if they weren't direct threats, those moments give her pause.

"I'm an outspoken Black woman," she said. "It makes me very nervous because I'm easy to find."

Something else on her radar: there's been a mad dash in 2020 for guns and ammo. She keeps a box of 9 millimeter rounds for emergencies because she hasn't been able to find any in stores lately.

Kris Emery, owner of the ammo manufacturer Mountain City Supply in Denver's Lincoln Park neighborhood, confirmed that's true. He's been trying to source materials from places like Croatia, since the stuff that makes bullets fly has been in short supply. He said he's not seen a shortage like this since the Obama administration, at least.

And, as of September, records from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation show twice as many concealed handgun permits were approved in 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. There have been 30,000 more approved gun sales so far in 2020 than in all of 2019. In the last six years, only 2016 has this year beat for total approved sales - for now.

James does not like the fact that there may be more people walking around with guns. But if they are, she said, she wants people from her community to be prepared.

"I would be happy if America had no guns," she said, "but that's not the reality of where we're at."

For James and her instructors, gun ownership is also an issue of racial justice.

While the Second Amendment should be accessible to everyone, James said Black communities have long had difficult relationships with guns.

"The murder of Black men, gang warfare and, unfortunately, the issues that surround poverty make gun ownership in the Black community something that has been a negative for a very long time," she said. "Black Americans have been taught: Good Black people don't have guns. Bad Black people do have guns."

While they may be "fallacies," James said, these ideas have limited African Americans' full access to their constitutional rights: "We want to change that."

Heru, her instructor, put it bluntly in terms of freedom.

"For me, it's very important for African Americans to own guns," he said. "Everybody else owns firearms, and I think a people who are not able to defend themselves are subject to enslavement."

James and Heru are quick to point out that anyone is welcome at 17 Seventy, and their training is not all about personal defense. They're both interested in moving people toward competitive shooting and hunting. Still, Heru said he's happy that he can connect intimately and immediately with Black people who come in to learn.

"Being able to pass along that skill, it gives me a sense of pride and a sense of joy," he said.

His pupils appreciate it, too.

Eric Hill, who drove from Centennial to get his conceal-carry certificate on Saturday, said access to Black instructors was an instant selling point. He's been a gun owner for about a decade, but he's never taken a class like this before.

"That was one of the determinant factors that made me want to come here, the fact that it is Black-owned," he said. "As a Black young man, it's important that we teach our people around gun laws."

Having Black instructors to teach Black students addresses another issue: Gun ownership comes with heavier baggage for people of color.

Americans of all races are likely familiar with "the talk" by now. As police killings of Black people have sparked national protests, there's been a lot of public attention on the discussion Black and Brown parents have with their kids about interactions with the police.

17 Seventy's co-owner and CEO, Shawn McWilliams, said there's a similar paradigm when it comes to owning a gun.

"Most people think that if you're African American, you don't understand the rules of having a handgun. You don't have a [conceal carry permit], you've never been trained. So the perception is also what we're trying to combat," he said. "That is a hard process to go through when you are treated differently because of your skin color."

It can be dangerous to be both armed and Black, McWilliams said. He had a career in the Marines, but he's still run into that risk recently.

On Sept. 26, he was acting as a badged marshal for a "march for Black women" when, after the rally, he walked politician and pastor Stephany Rose Spaulding to her car. After she drove away, McWilliams and another man were surrounded by Denver Police officers dressed in riot gear. They searched him and found his concealed pistol - which contained a banned, oversized magazine - then took him into custody as protesters began to gather around them. He was held at the downtown jail for a few hours, issued a ticket and a hearing date and released.

Neither Denver Police nor District Attorney Beth McCann's office would comment on why officers stopped him in the first place. McWilliams said his permitted weapon was concealed and that he never took it out of his belt. Less than a week prior, two white men guarding a livestreamer were ticketed for large magazines after one did draw his weapon; neither were taken to jail.

Shortly after his release, McWilliams told Denverite he felt "harassed."

How to legally carry a concealed firearm while Black, and deal with police if necessary, is the kind of tough conversation that he hopes will happen in classes at 17 Seventy.

"We want this to be a safe place to have those conversations," McWilliams said.

Though McWilliams and his colleagues all said they are not anti-police, they also said their safety sits squarely on their own shoulders.

"The idea that police are going to be there to protect you all the time is a fallacy. We call the police after the crime has happened," James said. "If you've got five minutes to deal with you and a bad guy, you're going to want to make sure that you're living at the end of that five minutes to be able to talk to the police about what happened.