It's almost time for the city government to approve another neighborhood plan, and that means it's time for locals and elected officials to debate how things should change.

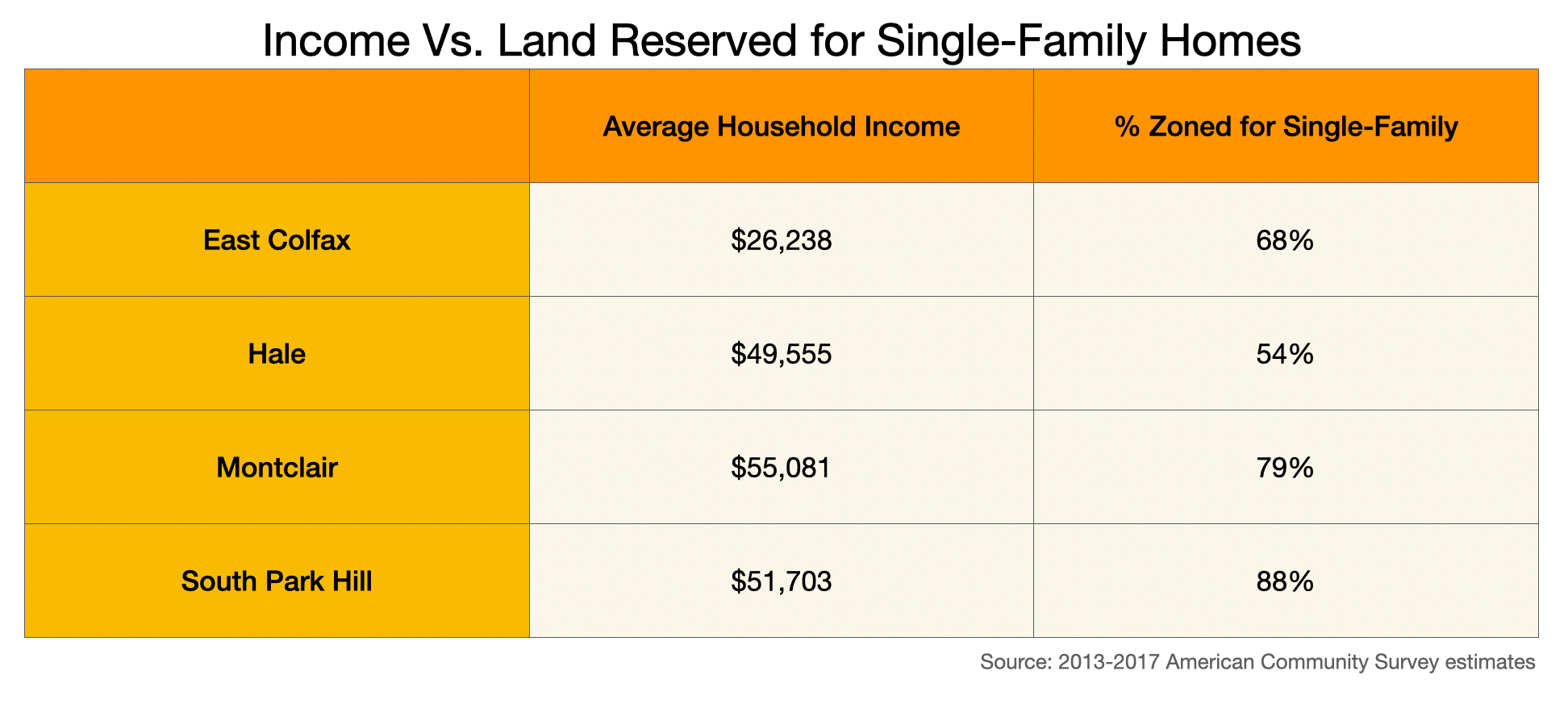

Front and center right now is the East Area Plan -- not to be confused with the Far Northeast Area Plan or the East Central Area Plan. This one covers the neighborhoods of East Colfax, Hale, Montclair and South Park Hill, and is anchored by the bus rapid transit project coming to East Colfax Avenue. City planners, residents and elected officials have worked on the plan for three years.

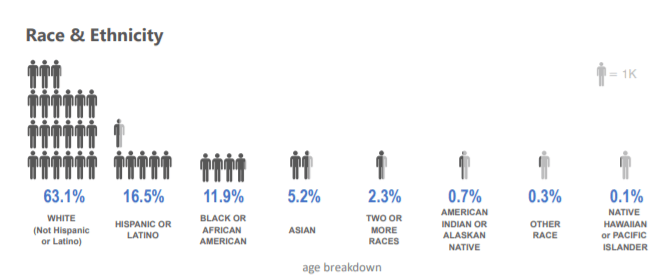

The neighborhoods combine for a little over 33,000 people living in 15,533 homes, according to the plan, which uses Census estimates from 2015.

What the plan is: a framework for growth and development in a city that will continue to grow and develop and is subject to the whims of a private sector that builds what the market demands. Often what makes homebuilders the most money is not what the city needs (read: affordable housing), so the plan recommends policy changes aimed at getting those things.

What the plan is not: a change of policy. It does not change zoning rules, which dictate what type of stuff can be built where. It's up to the Denver City Council to change those rules down the road with the help of the East Area Plan's recommendations.

The East Area Plan is the latest in a series of initiatives that will give every city neighborhood a documented growth strategy. It is based on a mix of urban planning goals set by the mayor's Department of Community Planning and Development, input from residents and city council members, and broader, previously adopted plans. It is a draft document until the city council approves it.

A single sentence in a 255-page plan has caused a lot of angst.

"Single unit areas should remain primarily single unit." In other words, neighborhoods made up of single-family homes -- that classic American home with a yard and sometimes a fence separating it from its neighbor -- should mostly stay that way.

The problem with that, say some residents and business owners, is that neighborhoods that allow just one type of housing exclude certain types of people. Duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes and apartments tend to be more affordable, but they're banned in most of the city.

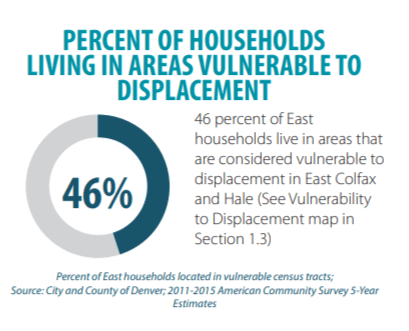

Pastor Nathan Adams argues that if Denver doesn't diversify housing options in more neighborhoods, those neighborhoods won't become economically or racially diverse. He also says people are at a higher risk of being displaced if the city funnels new development to lower-income areas like East Colfax, for example, instead of spreading it out across all four neighborhoods.

"We need a plan that is willing to make some people, some neighborhoods, more uncomfortable than others so that our most vulnerable neighbors can remain in our neighborhoods and our city as our neighbors," Adams said during a meeting of the East Colfax Collective earlier this month. "We feel an emphasis on single-family unit zoning continues to perpetuate decades-long acts of racial and economic injustices."

Adams and his group, the East Colfax Community Collective, opposed the plan in part because it doesn't get rid of single-family zoning altogether like Minneapolis has done citywide. Doing so would theoretically result in more multifamily buildings, either from big houses being cut up into smaller homes or from new builds.

On the other side of the issue are people like John Sawyer, who testified against the plan during a meeting of the Denver Planning Board earlier this month. He said the strategy to diversify housing in traditionally single-family neighborhoods is "an attack on neighborhood stability and tranquility, and it's all kind of cloaked in language about fairness, affordability, equity, etcetera."

Sawyer scoffed at the idea that the plan would guide the free market toward building affordable homes or that more density, which helps walkability, would make a dent in climate change. He called the East Area Plan a "covetous effort by the city to fatten its tax coffers by increasing density in our neighborhoods and essentially ruining our quality of life."

The planning board passed the framework onto the city council after deleting the controversial sentence. Council members say they will add it back. Does any of that really matter?

Denver Planning Board members voted 6 to 3 to pass the plan without the sentence. Some worried it could be used in the future to deny requests by homebuilders to construct something other than a single-family house.

But board member Gosia Kung pointed to maps and other recommendations in the plan that make clear single-family neighborhoods are a core value with or without that sentence. She voted against the plan because she felt its recommendations for more diverse housing options, though strewn throughout, were not strong enough.

"I think it goes deeper than just amending a sentence or two in the language," Kung said. "I think it's more embedded in the plan itself."

City council members Amanda Sawyer and Chris Herndon, who represent areas within the plan, said they will add it back before the full legislative body votes. The sentence amounted to a "middle ground" after years of debate, Councilwoman Sawyer said during a land-use committee meeting Tuesday. She said the plan balances new density with single-family areas with or without the sentence.

Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca said the East Colfax Community Collective, the group of mostly people of color that pushed to deemphasize single-family zoning, was being marginalized by the plan's "blanket protection" for single-family zoning.

"What that suggests to me is that a very challenging group to reach took an opportunity to express their self-interest and advocate for justice and they are being discounted because they didn't have the same opportunity to engage throughout the years," CdeBaca said.

City planners Liz Weigle and Curt Upton said the small-area plan is not an appropriate place to address sweeping changes to traditional single-family neighborhoods. The point of the plan, Weigle said, is to recommend "a smattering" of density -- more homes and businesses -- throughout the neighborhoods in places they're currently banned.

Wait a second. If that sentence is only somewhat important, what else does the East Area Plan do?

The East Area Plan's first priority is to make its four neighborhoods "equitable, affordable and inclusive," it states. Easy, right?

The Department of Community Planning and Development believes the Colfax transit project will make the area more attractive for developers. So they're urging the city council and mayor to change regulations in a way that incentivizes the building of homes for low- and middle-income residents or other "community benefits" in exchange for taller building allowances.

Other strategies aim to reduce unemployment and stabilize businesses at risk of displacement.

But those are just a few recommendations of many, many dozens. Here's a 30,000-foot view that should be helpful.

The Denver City Council will vote on the East Area Plan in November.