The lives of two men in Denver share striking similarities, yet they face drastic differences during this pandemic. Both began from humble beginnings, worked long hours to secure their own version of the American Dream, and operate businesses that rely on yards of fabric and needles.

Steve Duman is 68 years old. He runs Duman's Custom Tailor, founded by his father, Maurice, on Colfax Avenue in 1962.

Vince Cox is 70 and operates House of Blessing Custom Upholstery on 28th Avenue in Skyland, a business he helped create in 1984.

Both are masters of their crafts.

Cox witnessed a boom in business as COVID-19 lockdowns dragged on. As more people started working at home, they started noticing their furniture could use some love. He's never been busier.

"Yeah, this is overwhelming," he said. "That's a blessing."

Duman is wrestling with an opposite fate. As steady restaurant clients no longer needed aprons and chef coats, as weddings tapered off and bridesmaids no longer came in for altered dresses, the money slowed down considerably.

"We're almost going out of business," he said.

Vince Cox arrived in Denver without much more than a strong work ethic.

"We all was born in Mississippi on the plantation. Work and needing a job pushed us this way," he said.

Cox and his half-brother were both born to sharecropping parents who lived rent-free on land between Belzoni and Morgan City, Mississippi, an old plantation town that's "not on the map." What they saved in expenses, they made up for in work. Their families raised most of what they ate from the soil, from hogs to greens. The money came from cotton.

"It's long work," he said. "$3 for 100 pounds. I never got my $3 because I couldn't pick 100 pounds."

He remembers his childhood fondly. It wasn't easy, and though his home had no utilities to speak of, he believes he developed an understanding of money and work that's stuck with him all these decades later.

"I'm so proud and so thankful that I grew up that way," he said. "I make the money. Money don't make me."

He volunteered for the Marines after the Vietnam War began. He would not wait around to be drafted. It proved to be a wise move. Instead of shipping off to combat in Asia, he was assigned to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where he trained for a possibility of deployment that never came. It was there he learned to keep his body fit. Even today, he works in his Skyland shop with five-pound weights around his ankles, keeping his legs in shape as he moves through the small space.

In 1984, Cox's half-brother told him to come out to Colorado.

"I was unemployed in Wichita, Kansas," Cox said. "He invited me here to help him."

Cox, his half-brother, his half-brother's sister and a friend rented a basement space along 34th Avenue in Cole, the street that would later be named Bruce Randolph Avenue. It began as the House of Blessing Thrift Store, which is what God told the friend to name it in a dream.

Cox had never upholstered a thing when he started. As they scoured streets and alleyways for discarded chairs and couches, refurbishing them for resale, he began to learn the craft.

Three years later, everyone but Cox had left House of Blessing. He was not going to let it go.

"It was in my blood. Keep a job," he said. "I don't like to ask nobody for nothing, except the good Lord."

The business offered him stability. But more than a source of income, it was his home.

"We didn't really have a place to stay," he remembered. The landlord "allowed us to move in that building, and work in the building. I lived in the shop. Guess what? I still live in the shop."

Around 2003, he shut his doors and left the city for about a decade. When he returned in 2012, he had the business' original phone number and client list. He rented the space on 28th Avenue, where he still lives and works, and began House of Blessing anew.

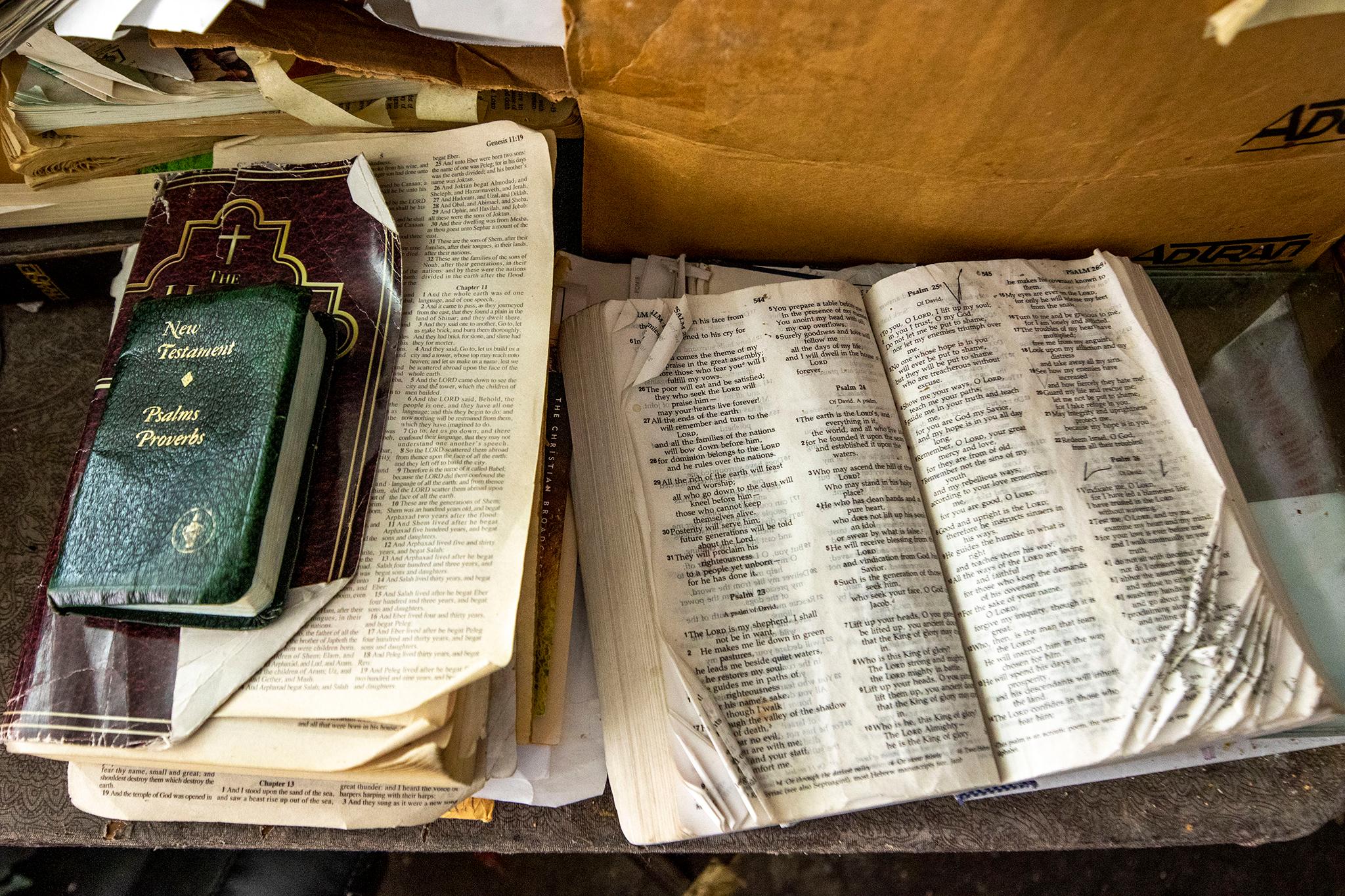

The table where he makes pillows and fixes worn chairs is his bed. When he rises each day, he takes off the padding and blankets, spends some time revisiting his favorite chapters of Psalms or Proverbs, and then gets to work sewing on the wooden platform.

His workload was the only thing that changed when COVID-19 cases began to rise in the city.

"I'm already quarantined, because I live here and work here. So I don't gotta go nowhere," he said. "I can work 24 hours."

Clients, Cox said, seek him out from all over the state. He's taken jobs from people who drove hours to bring in their loved, battered, belongings. His phone rang more and more often as the summer went on.

"I've never experienced this," he said.

For Cox, the boon represents a path toward something new. He owns two homes in Wichita, and he's angling to retire in one of them.

He'll likely not stop upholstering. One of the homes in Kansas is unfurnished.

"I'll be leisurely doing my own furniture, getting ready to live," he said. "I'm going to have furniture on the ceiling. Imagine me putting it on the wall!"

He plans to use extra material he's gathered over the years for his new pieces. When he's finished, his home will be filled with remnants of the career that got him there.

The House of Blessing became more of a godsend than he'd ever expected. He gives all credit to his creator.

"God blessed me with the finances to move back," he said. "God's answered all of my prayers. It's not about me. It's about my belief and my faith in our maker. That's it. I live it. I pray. I get healed. I get help. I get blessing."

Steve Duman has worked in his father's shop since his teenage years.

"I was conceived in Germany, and I was born in Denver," he said.

His father was Polish, his mother was Lithuanian, and their lives were both upended as Hitler's troops came after Jews like them. They met after the war in Lithuania, then moved together to a displaced persons camp in Germany. It was where his two sisters were born, and where his mother carried him until they had an opportunity to leave. By the time Duman was born, his family had settled along West Colfax.

His father opened Duman's Custom Tailor on East Colfax a few years later, just down the street from the Capitol. Duman spent time in the shop as a kid, helping his father when he was old enough. He also took jobs for the slaughterhouse companies that once stood in Elyria Swansea, back before it was swallowed by concrete infrastructure. He never expected trucking livestock between mountain towns and Denver would earn him a place in international history.

In 1973, Duman was in his third year at the University of Colorado when he attended Yom Kippur services at the BNH synagogue in Hilltop. It wasn't his usual place of worship. On that high holiday, Egyptian and Syrian forces launched a coordinated attack on territory that Israel had taken by force in 1967. The conflict became known as the Yom Kippur War.

"The rabbi turned around and looked at everybody, and said, 'Everybody dig in your pockets,'" Duman recalled.

Israel needed help, but he had no money to give. Instead, he had another idea.

"I looked at my friends. I said, 'Why don't we just go?' They said, 'Yeah, ok!'"

He'd learned the Israeli army was accepting help from international volunteers. When he showed up at the airport to fly to Canada, then Switzerland, and then Israel, he learned his friends' resolve did not match his own.

"We were all supposed to meet that day," he said. "I was the only one that showed up."

When he arrived in Israel's port city of Haifa, he watched as members of the army nearly tipped a brand-new truck cab as they attempted to unload it from a ship. He had to intervene.

"I said, 'I can put all these cabs over there,'" he recalled.

By the end of the day, he'd packed a fleet of trucks into a small space near the boat, ready to be deployed. Impressed, his new superiors tasked him with ferrying tanks and other gear into the Golan Heights. The mountains were not nearly as difficult as the terrain he'd driven in Colorado. He knew how to deal with shifting loads on narrow and twisting roads.

The war lasted just 19 days. By the end, he'd driven weapons and supplies into both of the conflict's fronts. Then, the army put him up in a kibbutz, a communal settlement, where he stayed and learned Hebrew for six more months.

That was the end of his college career. He returned home, married his fiancé, Sandy, and began to take the business over from his father.

While he never dreamt of becoming a tailor when he was young, he found a love for the work.

"I know what I'm doing, and I like what I do," he said. "A lot of people can use machines. But it's the architect that drew up that building that's truly the person who developed it. ... I feel like I'm more the architect."

When a client enters the shop in search of the right fit for a coat or some slacks, his hands and mind go right to work, sizing people and their items up exactly. He helped expand the shop from tailoring to making uniforms, embroidery and design. He captured contracts with all kinds of businesses across the region. Macy's department stores from across the Front Range sent him regular alteration work. Each month, he could count on checks from some 200 restaurants throughout the city.

But Duman's business plummeted after his clients evaporated in the pandemic. Wedding season didn't boom like usual. In-person court hearings ceased, and so did work for lawyers who usually came in with new suits. Orders from restaurants disappeared; some of those clients, like Racine's, disappeared altogether.

"You know how many aprons I've sold this month?" he asked. "Maybe a dozen. I was selling over a dozen a day."

When he learned the majority of Coloradans might not receive vaccinations until next summer, he balked.

"That's horrible," he said, eyes drifting to the street outside. "That's horrible."

While his landlord has been open to negotiating monthly payments, flexibility won't fix things. He's earning enough to make payroll, but he's dipped in his personal savings to pay the rent.

Vaccines did arrive in Denver this week. Duman hasn't given up hope on the family business, even though wider distribution of a vaccine still feels a long way off. If he's forced to close, he said he'll figure something out. He does worry about his employees, but he's not the type to retire.

"Not to work? No. It's not in my DNA," he said. "I didn't want to go out like this. I wanted to go out on my own terms, when I was ready. this feels like I'm being forced out, and that doesn't feel good. So I'm hoping that I can hang on."

Correction: This story originally misstated Duman's age.