Bettie Cram was one of the last residents of Elyria Swansea who could remember what Denver's northern reach looked like before it was covered in infrastructure.

In 2013, just a few weeks before her 91st birthday, Cram told her life story as part of a Denver Public Library oral history project. She arrived in Denver while she was still in high school. She told Cyns Nelson, the interviewer, that she soon started working at the nearby stockyards, weighing cattle that stepped off railroad cars.

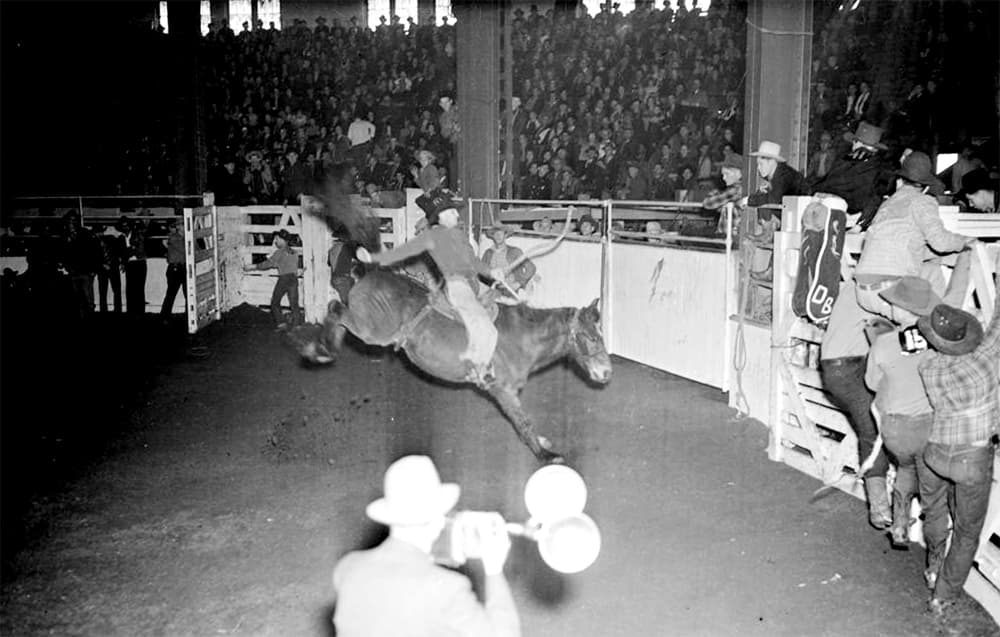

"I started work about 1941, and as I worked there, then I met one of the local cowboys. I married one of the local cowboys. We raised two children, two girls, in this area," she said. "Most of the people were from this area. On their lunch hours, they would ride their horses home. And it was just a fun, fun time that I felt I experienced in those years."

Cram died on Monday night, in the Josephine Street home she and Eddie, the cowboy, bought after they married. She was 98 years old.

She never forgot the way things were in those early days.

The changes she saw take hold in Elyria Swansea motivated her to advocate for the neighborhood. While she was always a known face throughout north Denver's streets, her profile rose when she joined the fight against the I-70 expansion project. She was in her 90s, but she rarely missed a public meeting or an opportunity to speak on behalf of fellow residents. She feared the neighborhood would lose the connection to its working-class roots.

Cram never got over I-70's original sin, the viaduct that split her neighborhood in half.

"When I worked at the stockyards, we would count the cattle. On a Monday we would get over 40,000 cattle in one day, 20,000 sheep, 20,000 hogs. In the fall, it was a wonderful place to work. Then they had the packing houses, and they would ship them right over," she recalled in her oral history. "The Livestock Exchange Building, which is now a historic building, had just like a little city. We had our lawyers. We had our banks. We had the restaurants. We had the Western Union. We had our own radio station."

But things in the neighborhood began to change, even before the highway project began.

"Then, finally, everything got kind of automated," she said. "The packing houses eventually quit because it got very modernistic. It was such a shame."

That was sometime around 1960, she said, as bigger changes loomed.

"After the packing houses closed down, Elyria really kind of fell apart."

Work on I-70 began in 1961, a massive project that built a raised roadway above 46th Avenue. It would be completed in 1964.

Cram said it "devastated" the neighborhood.

"They took out several houses. It caused a lot of chaos in the neighborhood," she recalled. "It kind of split the town to a degree. But we survived."

In recent years, when the viaduct began to fall apart, making renovation necessary, the Colorado Department of Transportation began to pursue a project that would lower I-70 below grade and expand it so more cars could speed through the corridor.

Resistance to the expansion began to take hold. Many activists hoped the crumbling infrastructure presented an opportunity to atone for splitting Elyria Swansea so many years before. They pushed for a "reroute," sending traffic north into Commerce City and allowing for the neighborhood to heal. Their alternative never gained traction outside of vocal protests, but Cram found her place in the movement.

"She was one of the main leaders. She never backed down," Drew Dutcher, president of the Elyria and Swansea Neighborhood Association, said. "She was so passionate about it. Sometimes she would call me and just start going off. 'How could we let this happen? Our neighborhood is being destroyed!'"

Robert Quintana is pastor at Pilgrim Congregational Church, where Cram played the organ from 1964 until just two weeks before she died. She loved to play the old hymns. But when service finished and parishioners cleared out of the sanctuary, Debussy's "Clair de Lune" was her favorite piece to finger on the keyboard.

Quintana said Cram worried Elyria Swansea would forget its history and suffer a fundamental change.

"She didn't like the modernization. Not merely because of sentimental reasons, but she thought the neighborhood was originally built for those who were under middle class, and the changes were actually tearing all that away," he said. "She was very concerned about the neighborhood. Gentrification was a big deal to her, the loss of older buildings. She felt the character of the neighborhood was being lost, and she didn't like the highway being there."

She was just one voice in the fight, but those who knew her say she made a difference.

Her friend and fellow I-70 crusader, Fran Aguirre, said Cram had significant impact on the neighborhood outside of their fight with CDOT and the city.

She sold Avon products for years, going door to door. It was in this way that Cram kept in touch with her neighbors, one of her great loves in life.

"She knew everyone," Aguirre said. "She loved the neighborhood, and she really cared for the people."

The pandemic didn't stifle this, Quintana said. Instead of visiting people in person, she spent hours chatting with friends on the phone.

She loved animals, too, particularly a "colony of feral cats" that she fed daily in the alleyway behind her house. Aguirre remembered they swarmed the fences, greeting Cram as she made her way to Aguirre's car, usually en route to another meeting about renovations to the highway or her beloved National Western Center.

Cram's activism was not limited to speaking in public forums. She wrote scores of letters to officials, governors, mayors and CDOT brass to voice her views on the neighborhood's future.

Dutcher recalled one meeting where she approached Don Hunt, former head of CDOT.

"Yes, I read your letters, Bettie," he recalled the official telling her.

While Cram and her fellow Ditch the Ditch protesters were ultimately unsuccessful in derailing I-70's revamp, the city did honor her with "Bettie Cram Drive," a small section of road in the National Western Center's new campus.

Dutcher said it wasn't a "condescending" move.

"They knew they better listen to her and respect her," he said.

Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca, who gained her seat in part because of her involvement in Ditch the Ditch, saw that moment differently.

"They exploited her memory of the Stock Show to elevate her as a community representative for the destruction," she said, "in the name of protecting community and honoring our past."

But Cdebaca said Cram still impacted the future in other ways.

Once the viaduct was complete, Josephine Street became a major onramp to the highway. Cram's duplex suddenly opened onto a busy thoroughfare. Her memory of the neighborhood's past helped CdeBaca imagine a future for Elyria Swansea, a vision she could fight for.

"That context was always really important to the conversation, because so many people didn't have that," she said. "For her to even remember a time when she could walk out in front of her house and cross the street, that was such an important memory. That created a memory for me."

Cram had a complicated history with other changes in the neighborhood. In her interview for the library's archive, she mentioned an influx of Mexican immigrants "was very hard on the neighborhood." But CdeBaca said she learned to overcome the racism that she was "conditioned" to internalize. When Cram died, CdeBaca said she heard from Latinas who worked with Cram on neighborhood issues. They cried over the loss of their friend.

"Bettie was one of the few people in the neighborhood who wrapped her arms around them and welcomed them to activism," she said.

CdeBaca said it was her actions, not necessarily her words, that engendered trust within Elyria Swansea's diverse community.

Dutcher said her commitment to working people bound Cram and her neighbors together.

"She had a vision of a neighborhood that was very self-sustained. Working class, hard working people that were very self sufficient," he said. "Bettie was a real leader of the community. People trusted her. She had a lot of street cred."

Maxine Ichikawa, her best friend, said they were like sisters.

"I will never find another friend like her," she said. "Never. Never."

At the end of her life, Quintana said, Cram's moved on from fighting the highway. Instead, he said she fought for independence. She lived her whole life under her own direction, and she did not want to live in a nursing home.

"It's almost prophetic that she passed away in her own bed," the pastor said. "She left here on her own terms."