In 2014, a project known as "City Loop" died under the weight of neighborhood ire. Denver officials had $5 million and a "futuristic" design to revamp City Park's playground, but the process buckled when loud voices in public meetings raised concerns about parking shortages and children's shrieks they said would shatter the tranquil air.

"When it got rejected, the money was still there. The commitment was still there," Paul López, Denver's Clerk and Recorder who represented the west side on City Council back then, remembered. "I called Parks and Rec right away, and I said, 'We want it.'"

The city identified a possible new home for the funds: Paco Sanchez Park, where Knox Court meets Lakewood Gulch. It would completely transform what Deputy Executive Director Scott Gilmore called "an embarrassing playground" that was a quarter-century old and in "horrible shape," he said. Even though parts of López's district had been underfunded for years, he said the idea to move the money across I-25 still faced pushback.

He and Gilmore both held a public meeting to pitch the idea to west side residents and make sure they had buy-in. Gilmore said 75 people showed up. López said lower-income residents, "folks in the projects," badly wanted something nice near their homes. But wealthier "curmudgeons in the neighborhood" objected, he said, and feared the improvements amounted to "gentrification" that would damage the neighborhood's peace and character.

"In the back and forth of this meeting there's this little old lady," López said. "I call on her. She stands up, puts her hand up, and says, 'I think the kids here would love this.'"

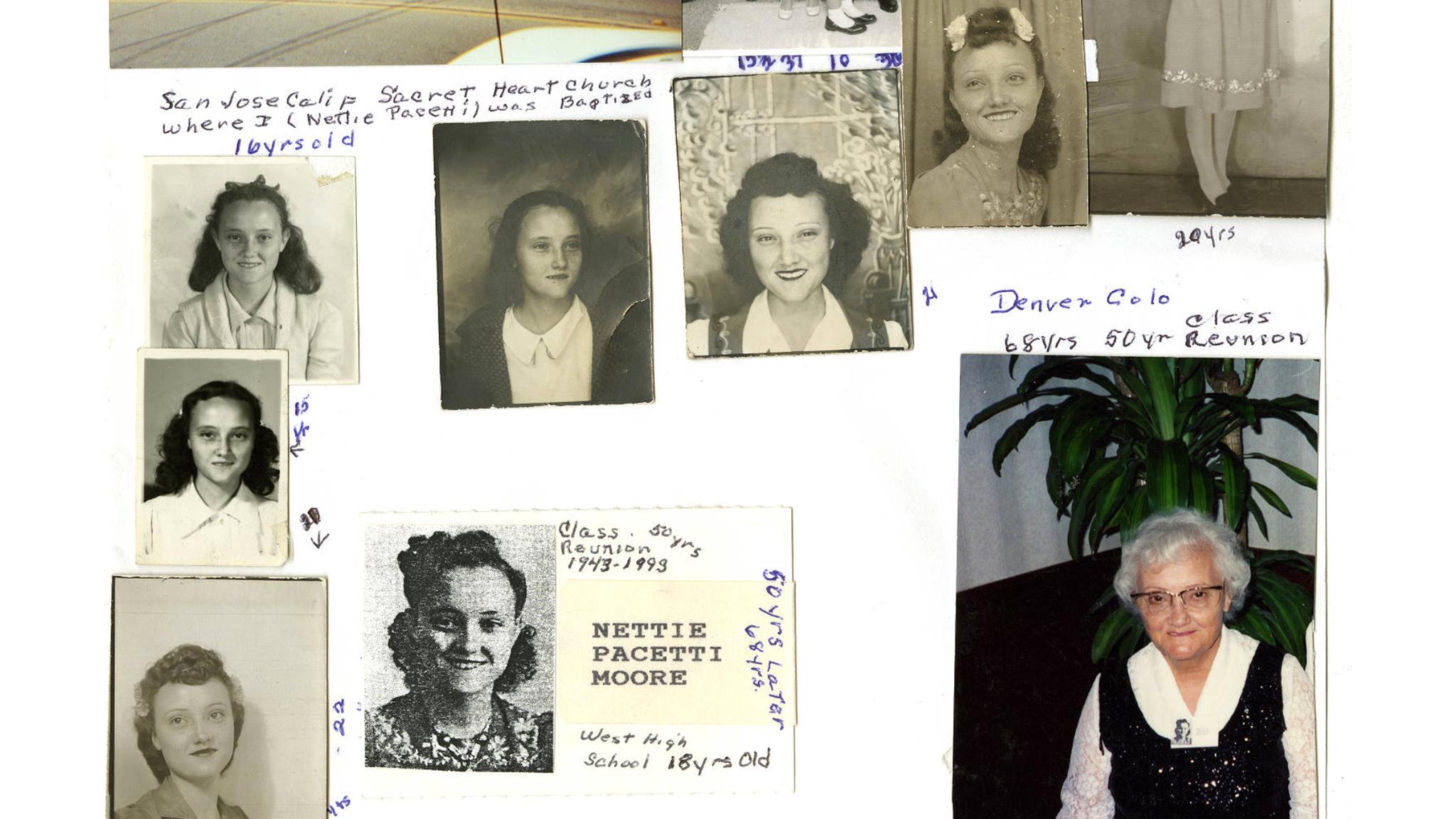

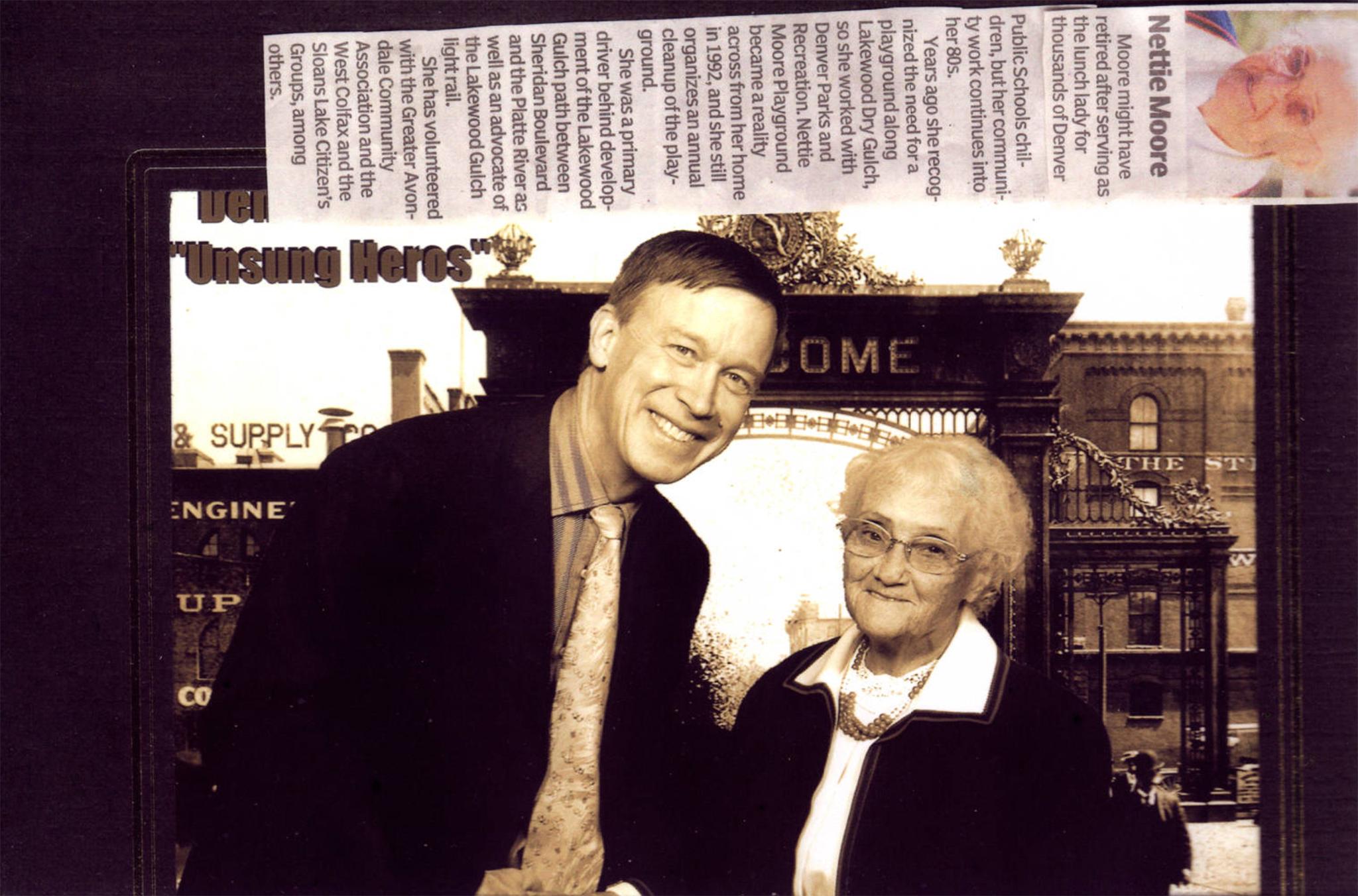

The woman was Nettie Moore, who was 89 at the time. She'd lived just a few blocks from the proposed site for nearly a century, predating Paco Sanchez Park altogether. She was known as the unofficial mayor of the neighborhood by the time she stood to speak in that meeting. When people like Gilmore wanted to do anything on her turf, they knew to run it by Moore first. And when she spoke, her neighbors listened.

López called for a vote on the project.

"Nettie put up her hand, and 75 hands went up," Gilmore said.

The west-side park would get its futuristic playground.

In an interview at her home last Friday, Moore said she could never help herself from weighing in on improvements, be it to parks or affordable housing stock.

"It was to give a proper type of living facilities for the people," Moore, now 96, said. "To try to keep it to a development that we're proud of."

Earlier in the day, Gilmore delivered a massive card to her home on Utica Street, thanking her for her involvement in the Paco Sanchez project and her broader stewardship of public space. He's always checked in with Moore, and he'll be visiting more regularly now. She's 96 years old and she "still has that fire," but her pacemaker is failing. He wants to make sure he gets as much time with her as he can.

"I don't have long to go," she said.

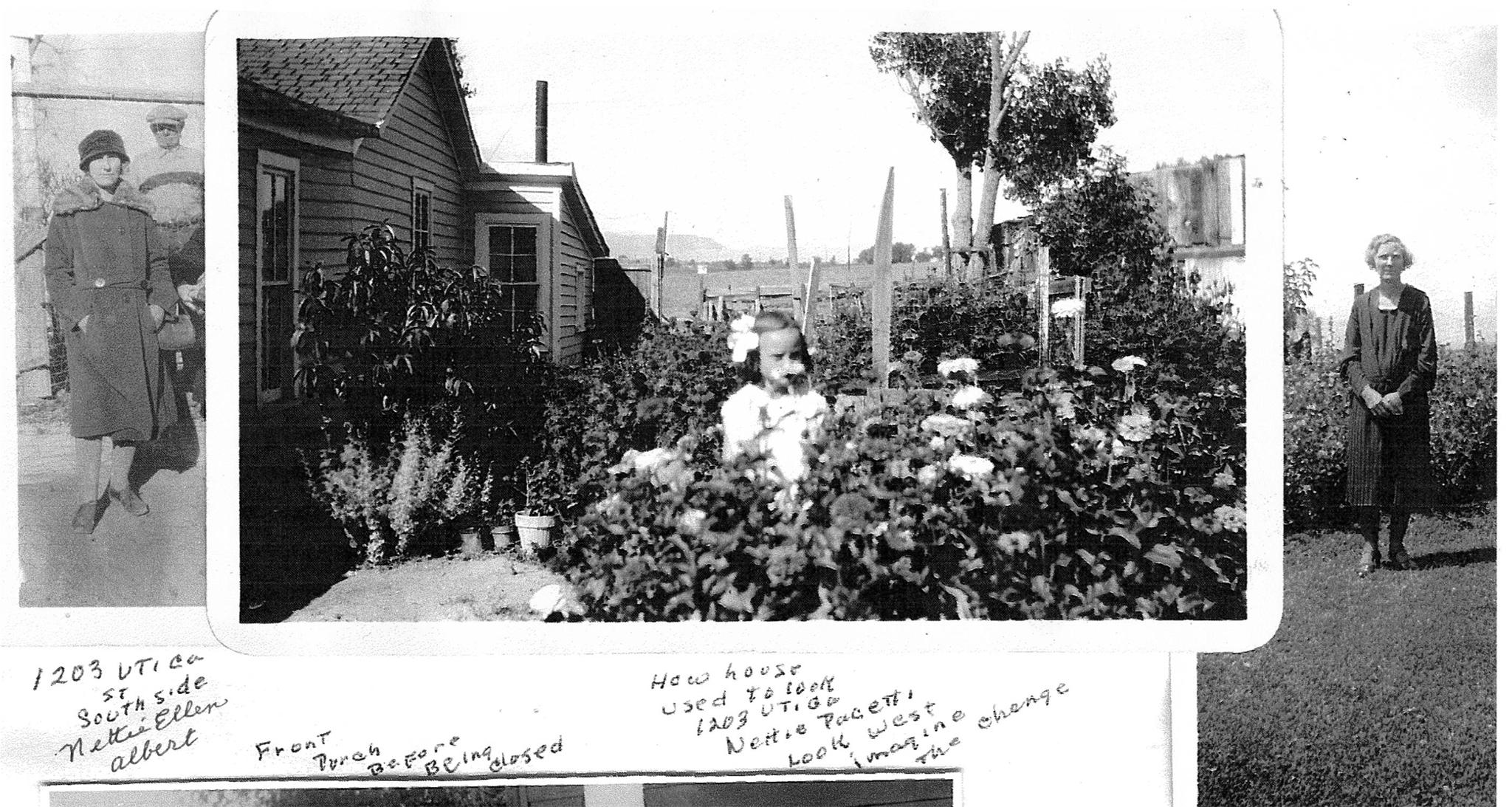

Moore has lived on Utica Street since 1927, before the road even existed.

She grew up at 1203 Utica, in a house her father bought new for $1,000. Grasslands surrounded the home, one of the only structures around, and living was rough compared to modern standards.

"From 13th (Avenue) south was like Little House on the Prairie," she said. "We had no electricity. No gas. We had the outhouse. And it took years to start to get anything done."

Lakewood Gulch, which bordered the property, was a lowland and a dumping ground, a place where stolen cars were abandoned in the night. When the city began to connect utilities and infrastructure to its rural extremities, Moore said, they often overlooked land near her family's south of Colfax Avenue.

Denver Public Library/Western Hi

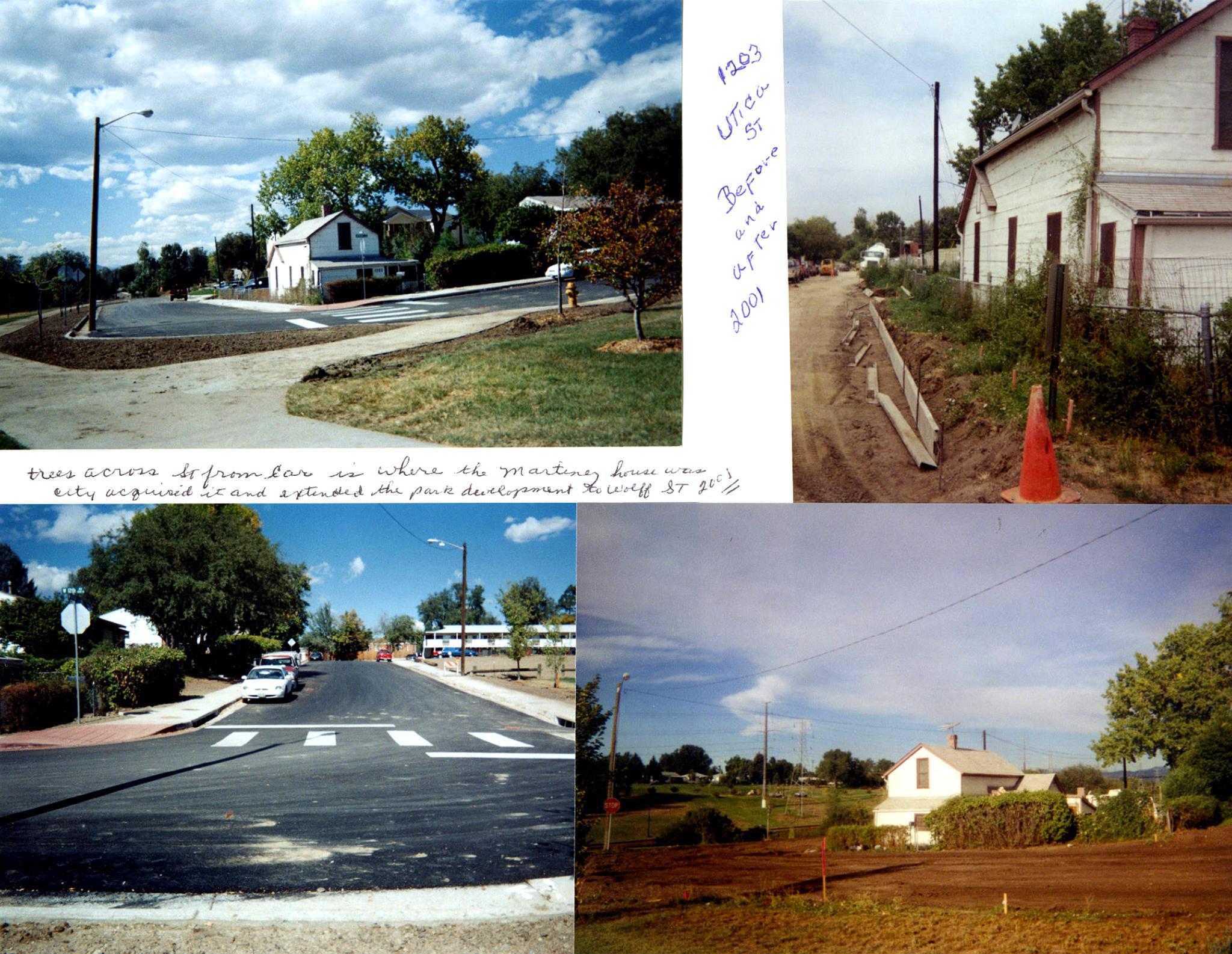

In those early days, Colfax was nothing but two single lanes that stretched between the mountains and the eastern plains. When officials began work to widen the street, an accommodation for a city beginning to leave its pioneer roots behind, Moore's father asked Denver for leftover dirt so he could build a rudimentary road down to his property. Moore and her husband, Dick, moved into their house next door in 1955, after they were married. The way to their home wouldn't be paved for almost 50 years.

"It stayed a dirt road until (Mayor Wellington) Webb came into office," Moore said. "Then I came along."

She asked Webb for "streets, curbs and gutters." In 2001, her wishes had come to fruition.

Her dad "got the dirt," she likes to say, "but Nettie Moore got the pavement."

Moore was already active in Denver's civic life by the time the asphalt was poured. Her advocacy was defined by a quiet, respectful insistence on what she felt was right for the neighborhood.

In the '90s, she learned officials planned to bulldoze part of a vacant lot across the street from her home to connect two fractured pieces of 12th Avenue. But Moore remembered that the lot's former owner left the land to Denver with the specific instruction that it should become a park. Moore had a friend who worked for the city, so she sent word that they ought to look into the matter.

"You're right, Nettie," the friend told her after some research.

With that, the plan was nixed.

Moore had other ideas for the patch of grass. At the suggestion of attorney Walter Cass, she applied for a $10,000 grant to build benches and play structures on the spot and won the money. When it was time to dedicate the new jungle gym, she said, her neighbors insisted they name it after her. Thus, the Nettie Moore Playground was born. From her porch, she could watch as children played on the spot she helped preserve.

It was not the last project named in her honor. In 2001, developers built an affordable housing complex behind her home, enabled in part by the paved streets that she pushed for. Moore said she showed up to meetings and weighed in on the developer's color choices and drawings. They listened to her on the color (she didn't like the original blue) and named the project the Nettie Moore Apartments.

Moore became passionate about housing. A decade later, her advocacy for the Renaissance West End Flats at Colfax and Zenobia Street earned her an award of gratitude from the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless.

Like Paco Sanchez Park, the Renaissance affordable housing project faced opposition from people who feared its construction would fundamentally change their neighborhood. A group of dissenters planned to take the matter to court. Once again, Moore became a vocal conscience for her neighbors.

"Well, I'm one of those people who feel like people have to have places to live," she said. "We're very fortunate to have Denver. We came from a cow town to what we are. And some will like it. And some won't. And the only thing, in my opinion, is we need places built for people to buy and have a home. ... This is progress."

She waited patiently for her turn to speak during public meetings. Then, without raising her voice, she pushed for what she believed in. She said that approach earned her the respect that turned her into a legend on the west side.

"Give other people a chance, even if you don't agree with them. Remember one thing: A raised voice doesn't always get anywhere," she said. "Now when I go to meetings I'm very well respected. I have respect for people, and they listen to me."

Gilmore, who grew close to Moore during his decade at the parks department, said she always embraced the city's evolution. She'd seen it transform more than any of her neighbors, so a green-light from her on a big project carried weight.

"She was always open to change," he said. "She was not so wrapped up in how things were that she couldn't move forward."

Moore gave her opinion on many more projects and attended countless meetings. She's collected awards, shiny groundbreaking shovels and letters from lawmakers. Developers looking to transform West Colfax into a chic, upscale destination have called on her to pay their respects and kiss the ring. She regularly attends Mayor Michael Hancock's State of the City address as Scott Gilmore's "date."

López said he's always felt compelled to listen to her because she is an "elder," someone who deserves everyone's attention.

"People like Nettie in our city are precious, and their involvement is a blessing," he said.

Gilmore choked up when he spoke about her.

"I want her to know how much we love her," he said. "I want her always to remember that."

Moore spent nearly three decades as a lunchroom manager for Denver area schools. She raised children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren from her home by the gulch. Beyond her impact on her built environment, she's touched an awful lot of people.

"I've had an eventful life and so many friends, you wouldn't believe," she said. "And when I go out of it, you know, I'm thankful."