As the pandemic seemingly winds down, Denver Parks and Recreation has decided which roads will remain closed to cars at six major parks and which will open back up to vehicle traffic this spring.

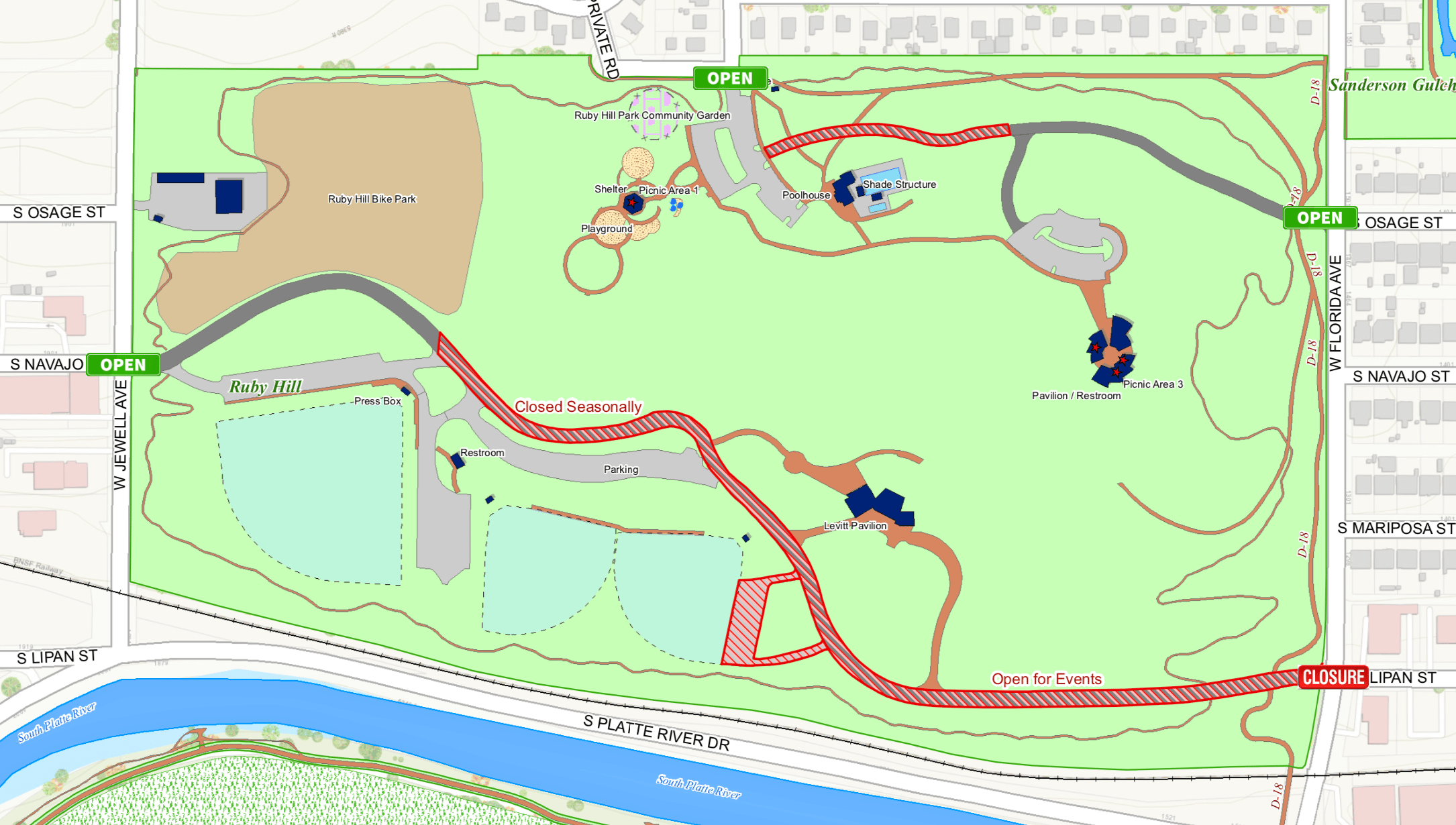

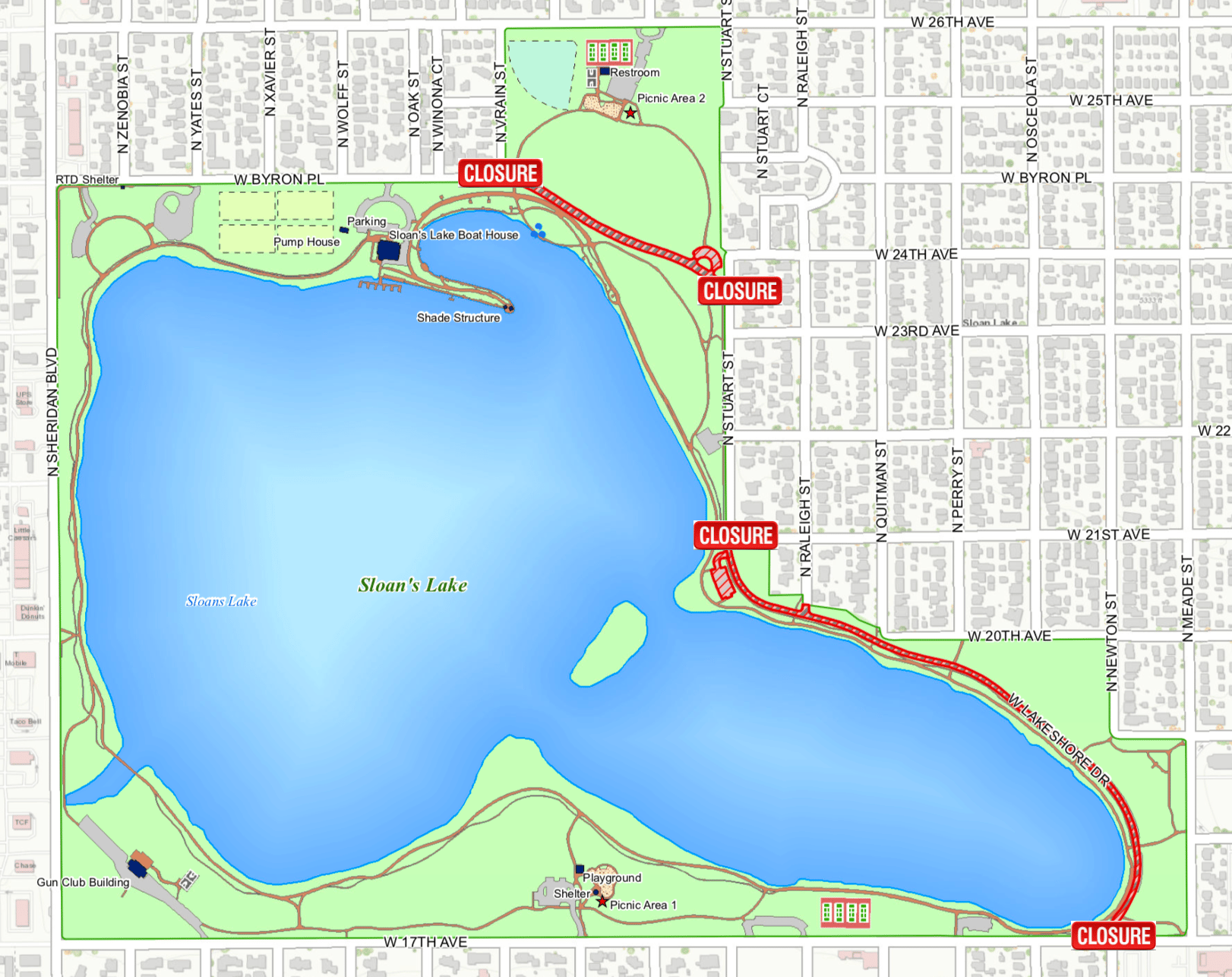

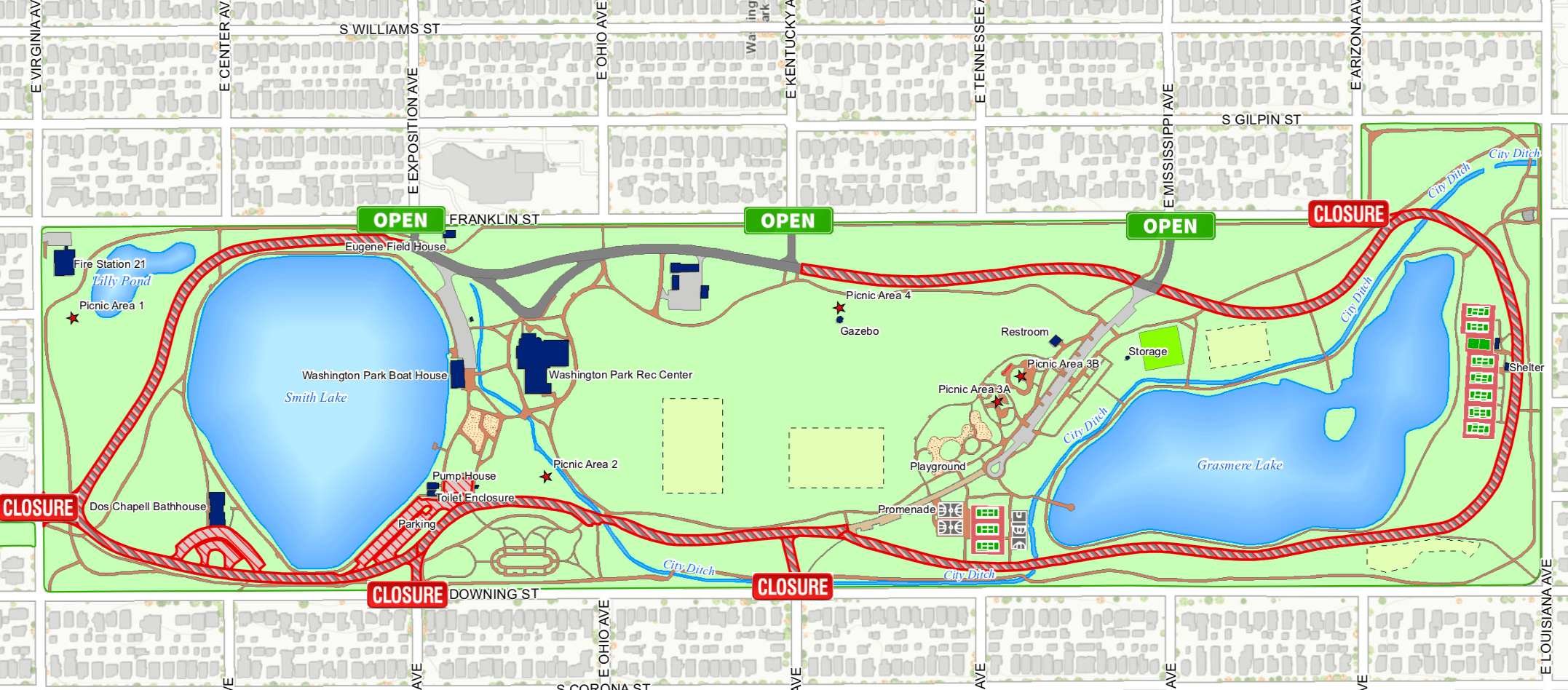

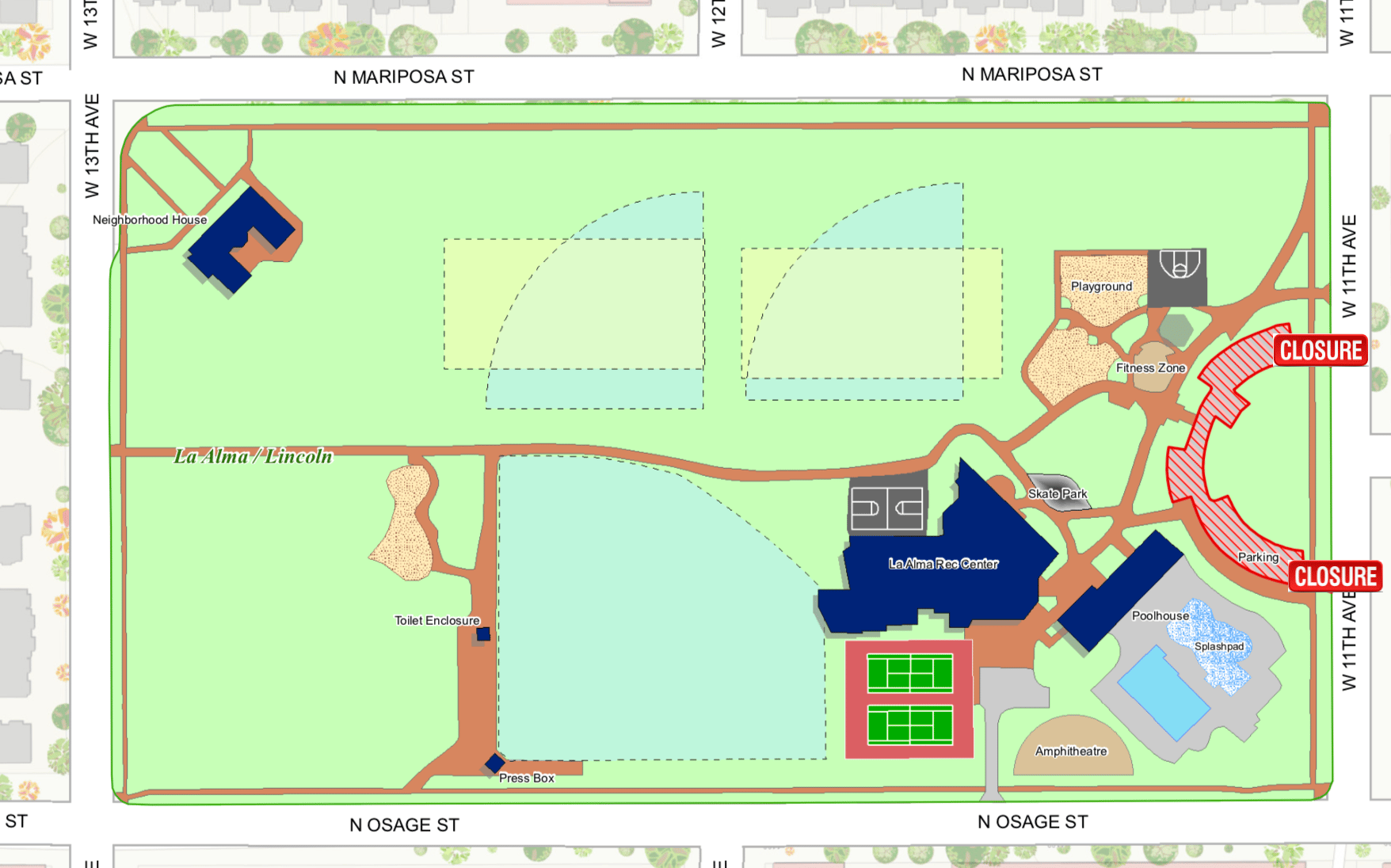

While drivers will be able to park in and drive through parts of Ruby Hill Park, Cheesman Park, Sloan's Lake Park, Washington Park, La Alma/Lincoln Park, and City Park come mid-April, segments of them will remain closed to cars. The decision comes after a nearly one-year-long experiment, prompted by the pandemic, to encourage physical distancing and make more room for people to get outside and stretch their limbs.

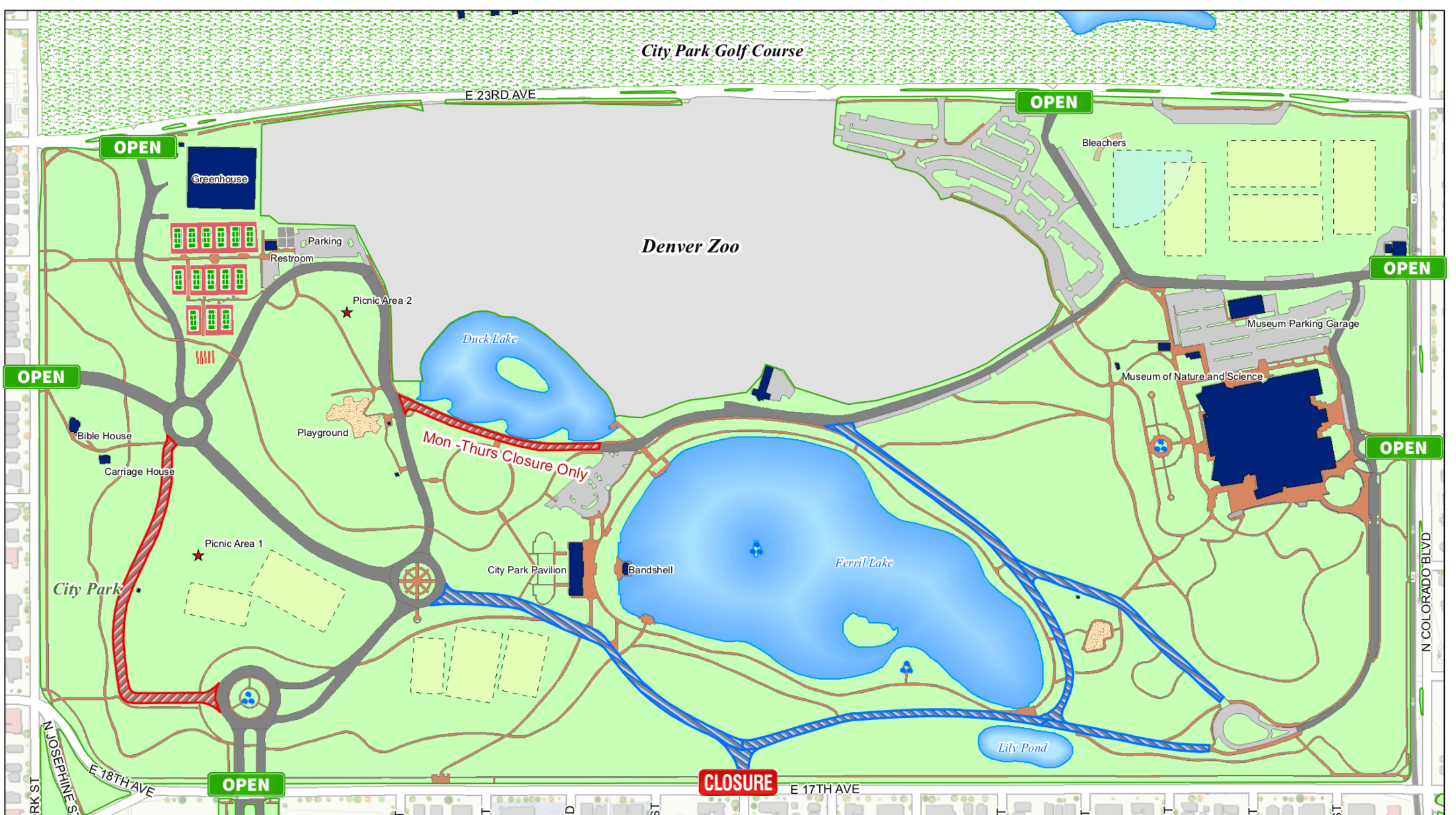

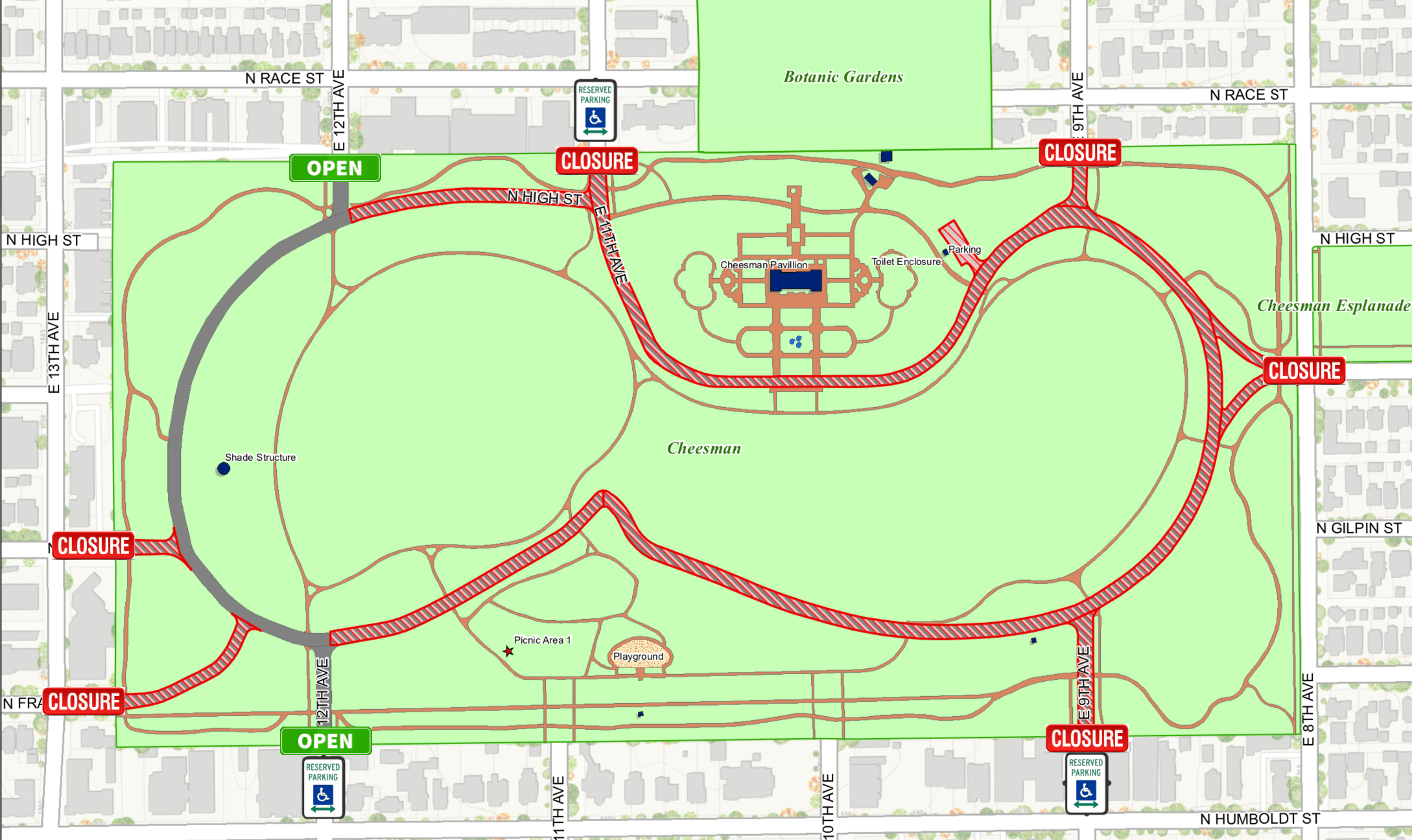

The likelihood of encountering cars depends on what parks you frequent. For instance, much of City Park will reopen to vehicles. But Cheesman Park, once a really big, pretty traffic circle, will remain mostly closed to cars -- and much more open to people walking, biking and rolling -- save for a northern segment that doubles as a bus route.

"I was just there a week ago. I just loved the freedom," said Jaime Lewis, who uses a wheelchair. He said being able to use the road instead of crowded sidewalks has changed his experience for the better. "You know, it was a great experience."

Enforcement in the car-lite parks, where people take it upon themselves to reopen parks to cars by moving temporary barriers out of the way, will get better, said Scott Gilmore, deputy director of Denver Parks and Recreation. His department is working on installing more permanent barriers.

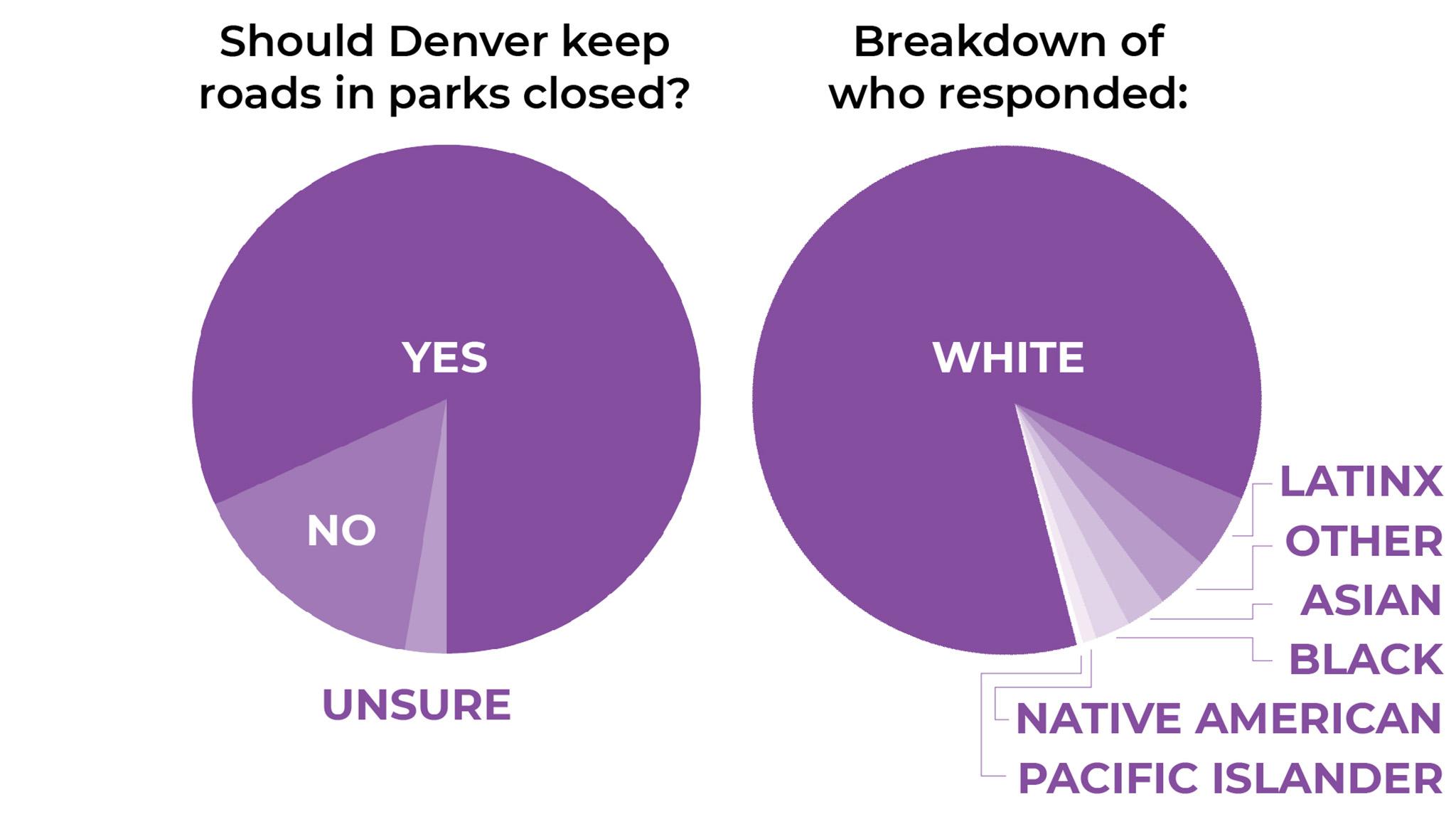

A government-led survey found overwhelming support for the parks to remain essentially car-free. Locals and visitors have loved the added safety and calm that comes with banning pollutive vehicles that conflict with people walking, biking and rolling. The survey of over 4,200 people found that 82 percent wanted to see park roads and parking lots stay closed. Even people who don't live near the parks in question said they'd like to keep cars out of them, but that majority was smaller, at 64 percent.

The people who responded to the survey, however, did not mirror the demographics of Denver. Respondents were overwhelmingly white, prompting Parks and Rec officials to pay extra attention to complaints that banning cars felt "exclusionary, elitist, or discriminatory," according to survey results. So Denver Parks and Recreation is welcoming vehicles back -- to an extent -- because officials say banning them is unfair to people who don't live nearby and people with disabilities.

"I feel pretty strongly about this," said Gilmore, who decided to open City Park's 23rd Avenue entrance after initially planning to close it. "Not everyone lives around the corner from City Park," he said, calling it Denver's "crown jewel." The map has changed -- it now reflects more streets open to cars -- since first presented to the resident-led Parks and Recreation Advisory Board in February.

Parks and Rec considers most of the six parks "regional" parks (as opposed to local parks), meaning they're meant to draw people from all over. According to the parks master plan, 85 percent of Denverites live within 5 miles of City Park.

Because this is Denver, parking played a role in the decision.

Lewis, who sits on the Colorado Cross-Disability Coalition, said his group has not fielded complaints about park access for people with disabilities. He's not a fan of drivers cutting through parks but said more parking spaces would be welcome.

Denver Parks and Recreation

Some people equate fewer parking places inside parks with being unable to visit them at all.

"We already lack good parks in several areas of Denver," one person wrote about Wash Park in the survey. "Don't prevent us from traveling to where the nice parks are from time to time!"

According to a pair of 2017 parking inventories commissioned by the city government, on-street parking spaces across 17th Avenue and York Street from City Park are plentiful during weekdays, but the inventory did not cover weekends. Several people pointed out to Denverite that parks are surrounded by streets where people can store their cars, even if it means walking a block or three.

"Do people need to have immediate access to like the center of the park?" said Matt Watkajdys, who supports keeping the parks completely car-free, and has argued with his neighbors on Next Door about this subject. "Denver is at the end of the day a growing city, and these are things that are trade-offs."

Many neighbors feel like the street space in front of their homes belongs to them, even though it is public. Gilmore said the decision is not up to neighbors. Still, neighborhood parking concerns took up significant space in the city's survey summary.

Denver Parks and Recreation

Conversely, Amanda Roberts told us she lives in a park desert, and the car-free experiment has actually increased her access to Wash Park.

"I walk to (and) around Washington Park more now since there is more space and fewer cars, and occasionally I drive to it as well if I am on my way home from another task that requires a car to access," Roberts said. "No issues with parking on the street, ever."

If New York can ban cars from Central Park, why can't Denver do it?

This, because Denver, also has to do with parking. Sort of. Parking lots are perceived to be so important -- and expected -- because driving is how most people get around here.

"New York is a very concentrated, very dense city where you've got subways, you've got buses, you got taxis, you've got all this stuff and you can get around the city really easily without a car," Gilmore said. "In Denver, if you don't have a car, it's a rarity. So I think to try to compare those two cities is comparing apples and oranges."

Yet on-street parking spots surround parks, even if using them means crossing the street to get to the trees and grass.