You got a letter from the city assessor this week if you own a home in Denver. Inside, you probably saw that your property is officially worth more than it was last year. A lot of homes rose more than 15 percent from their last assessment in 2019, and that is no small thing.

For some, that might be nice news! But there are residents in this city who are none too happy that they've got to pay higher property taxes next year.

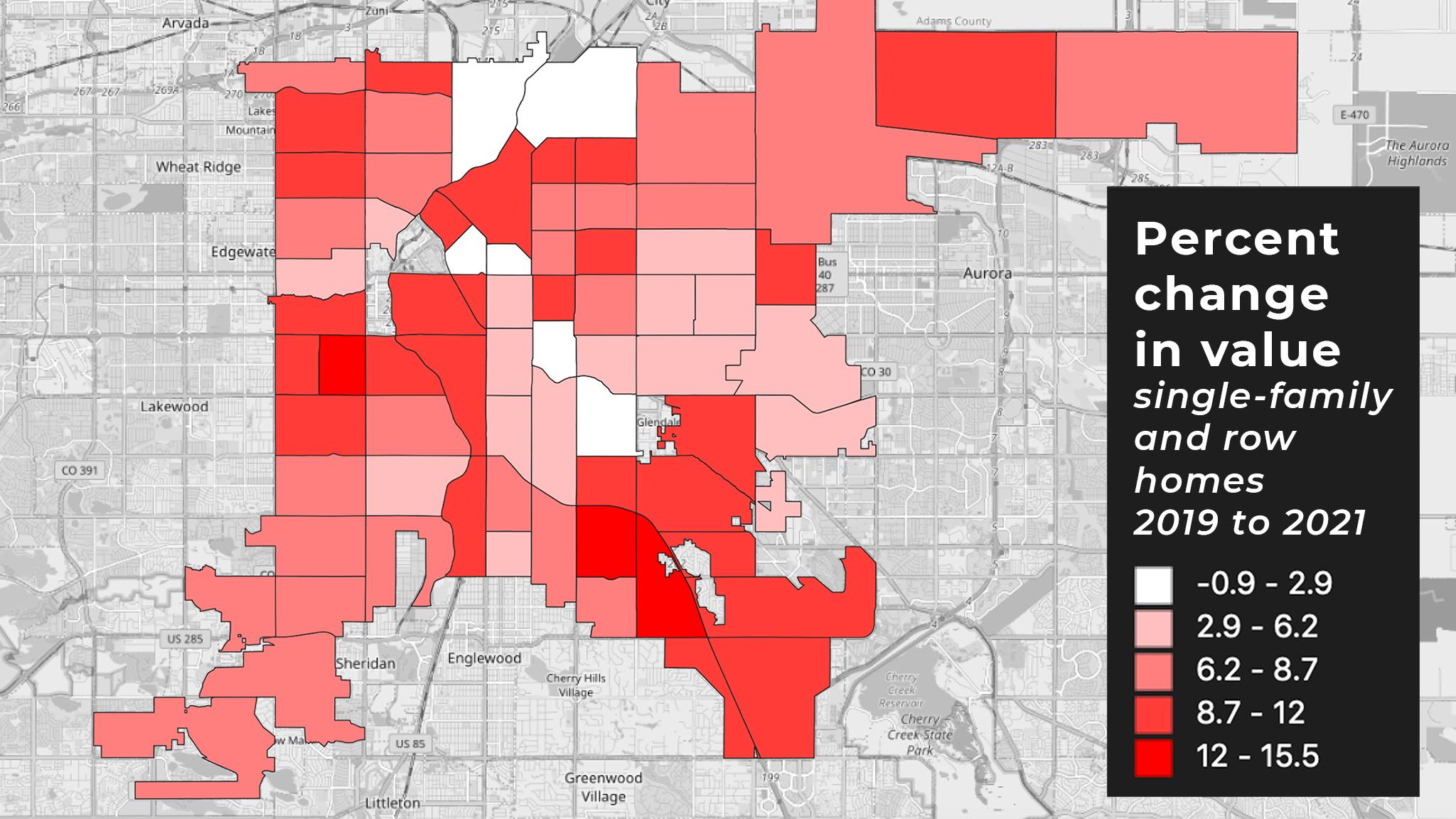

We dug into the numbers on this biannual valuation to bring things to the neighborhood level. According to our analysis, which was spot-checked by Denver assessor Keith Erffmeyer, neighborhoods on the city's west side saw a lot of big jumps in value. Barnum tops the list, with a median growth rate around 15 percent. University Park and University Hills, in south Denver, ranked second and third, respectively. We went knocking on some doors to see what people thought.

You can see the full neighborhood breakdown here.

But first, here's how assessments work.

State law tells Colorado assessors how and when to tally property values, which are the basis for your yearly property taxes. Every two years, beginning on June 30, they process all sales in their cities over the last 24 months. This data is the starting point for their new assessments.

Erffmeyer said his office feeds all of this information into a computer program that tries to group different types of properties into neat categories, then assign standardized prices to homes and lots. If you had two homes on the same block that were identical, for example, they should be priced about the same. If there was one more house next door with one extra bedroom, the algorithm would assign a higher value based what people were generally spending for extra square footage. If another house is identical but in worse condition, it might get a lower value. Et cetera.

Since these valuations are based on actual transactions, higher demand in certain neighborhoods can translate to higher assessments. Here's another over-simplified example: Imagine two identical houses on identical lots, but one is in Barnum and one is in Mar Lee. If buyers were more likely to get into bidding wars in Barnum, the home there will be priced more than its counterpart a few miles south.

Erffmeyer told us the city's assessment process is "a herculean effort," especially since they verify the characteristics of every single building sold in the city. He said that process makes their valuations more accurate than figures you might see on Zillow.

Finally, the city and state use Erffmeyer's numbers to calculate what you owe in property taxes. Denver has a base rate, and directs most of those collections to Denver Public Schools. You may also live in a special tax district, like one that collects extra fees for RTD, which will add to your bill.

Neighbors we spoke to in University Park were OK with the jump.

Samuel Ventola built his home on Monroe Street in the 1990s, and he's watched bigger houses go up around him. Two of his neighbors bought two lots each and built massive homes covering both parcels. He said an older woman who long lived across the street finally sold her small, whitewashed bungalow for the value of the land beneath it - about $850,000. It's already got a demolition fence surrounding it.

Many of the homes around his block saw sharp value increases this year. He wasn't exactly thrilled when he learned Erffmeyer's office bumped his property up by 20 percent, but he said it also wasn't the end of the world.

Source: Denver assessor's office

"This is a substantial portion of my theoretical wealth. On the other hand, if I'm not moving it doesn't help me," he said. "If you're not selling, it's just higher taxes."

Sometimes, he said, he thinks about cashing out and buying something bigger and cheaper in another town. He said it feels "irrational" to stay in a place that keeps getting more expensive. Then again, he likes where he lives - the neighborhood is quiet and close enough to downtown - so he'll stick it out.

A couple blocks away, Marc Carpenter said he's pretty much accepted the rising rates. His ranch home on Adams Street also got a 20 percent jump this year.

"We've been here for 30 years. We're not selling. We're not moving out. And it's just one of those things I don't lose sleep over, like death and taxes," he said, chuckling.

Carpenter said something else has given him comfort.

"We're blessed by having the financial ability to absorb those taxes," he said. "And also, paying more taxes is OK. The money's got to come from somewhere."

But budgets are tighter in Barnum, and tax hikes raised old fears of displacement.

Many of the blocks that saw the biggest property tax hikes in 2021 were also the most affordable. Erffmeyer said this is partially a mathematical thing, but it also has to do with the market.

"A lot more people can afford, and would like to purchase, lower priced properties," he said, "so these areas tend to have a lot of demand (even bidding wars) when properties come on the market."

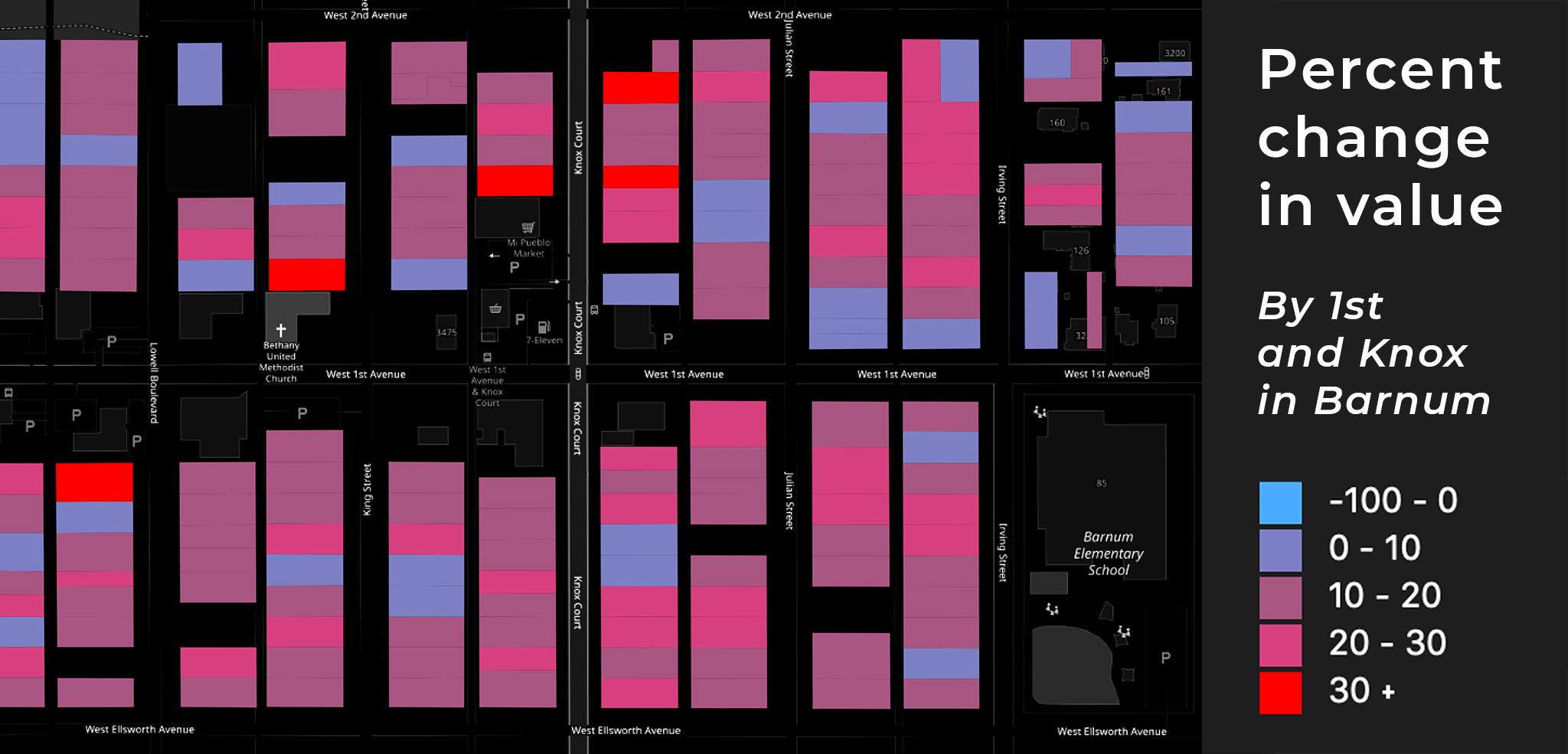

Source: Denver assessor's office

Source: Denver assessor's office

On Irving Street in Barnum, Anna V. (who declined to give her last name), said higher taxes can have dire consequences. Her parents have lived on Denver's Northside for decades, long before it became known as "the Highlands," and she said rising taxes have the potential to oust them from a neighborhood they love.

"I think it's going to push them out," she told us. "They could sell their house for a half million, easy. Buy a house in Thornton, half price. Get the extra cash. But this is a neighborhood that they've bene in for so long. It's home. Why would they move somewhere else?"

Denver does offer tax relief for some residents, including people 65 or older. Taxpayers can also appeal their official valuations.

On Julian Street, just south of 1st Avenue, Fawn Meyer answered the door at the home she bought in 1996. The property's value, and her taxes, have grown a lot since then, so she was ready for the assessor's letter.

"Two years after I bought the house, I couldn't afford to finance it," she told us. "In less than ten years, it doubled. And I mean, this is a small house."

Like everyone we spoke to, Meyer said she'd pay up, no matter how painful it might be.

"I planned for it, because I had to retire a while ago," she said. "It wont kill me, but I'm not happy about it."