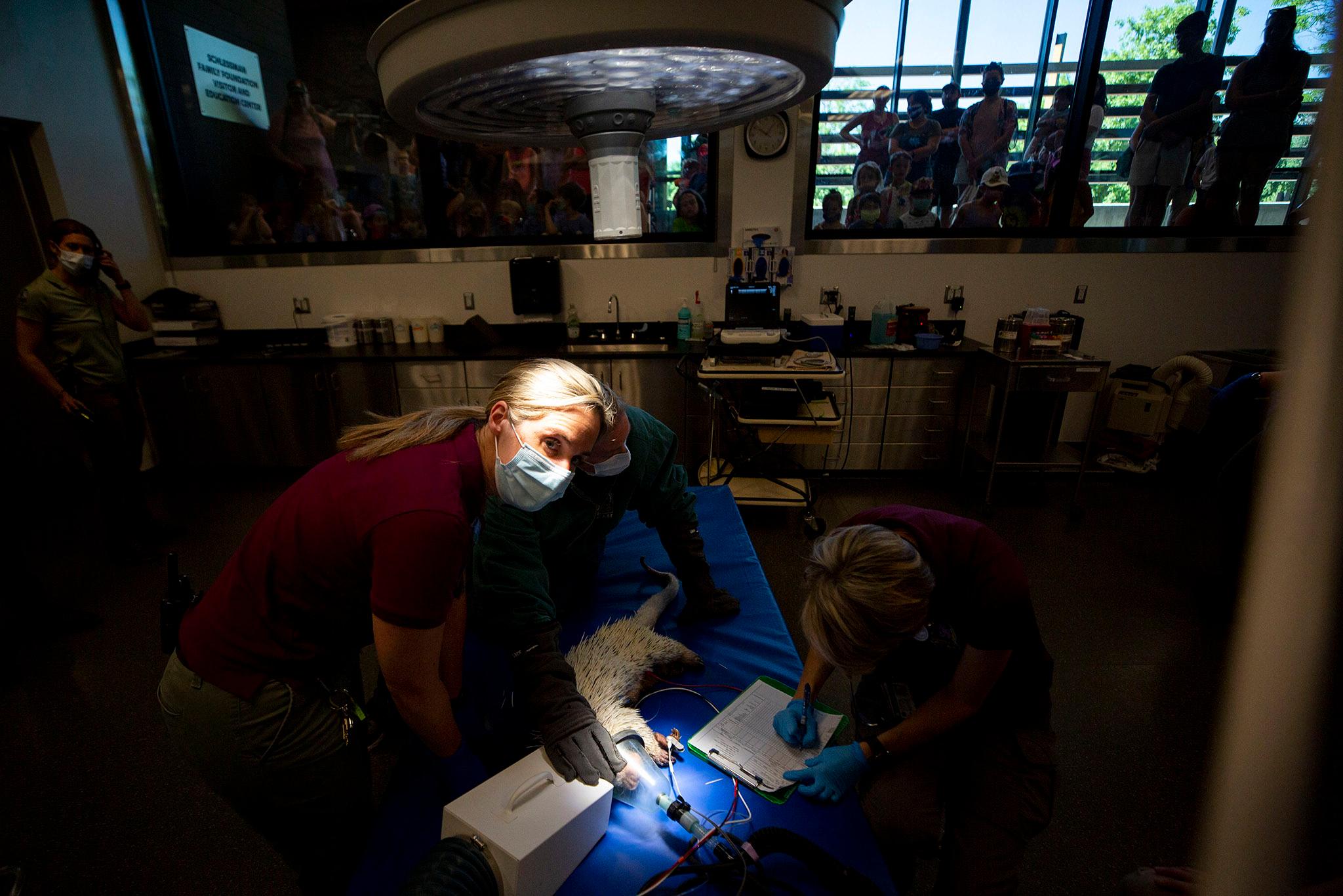

Dozens of little kids stuck their noses to the glass windows and watched as workers pushed Koko, the prehensile-tailed porcupine, into the operating room. The Denver Zoo resident is 17, pretty old for her species, and has been dealing with some dental and intestinal problems. It was time for her medical team to check in on her status. In particular, a stone had developed in her stomach and was probably causing ulcers. They put Koko to sleep, gently slipped her out of her crate and attached a mask equipped with anesthetic gas onto her nose.

"This part might be a little gross," zoo vet Dr. Lara Croft said to the children and parents watching above. Her colleagues were about to pull some of Koko's blood into a syringe, and it may have been a bit much for the young audience.

This has become a regular scene at the zoo since its new animal hospital opened in late May. The work of veterinarians was once invisible to visitors, but now their process is front and center. It's part of the story, beyond the public-facing enclosures, that the Denver Zoo wants to tell about their animals.

"There was great work happening, but all of it was all behind the scenes. I think it's really exciting to get to share with our guests all the work we're doing," Croft told us. "A lot of our guests have no idea what happens, how we take care of these animals, what we do with them. They're really fascinated to see that we're cleaning an otter's teeth or that we're doing an eye exam on a lion -- or even what x-rays look like on a penguin."

The new facility was designed to shed light on this work and enhance the care and research that goes on here.

There's a lot more space in the hospital than there used to be. The hallways are wide enough to wheel a tiger into the operating room. Medical devices are bolted to grids on the ceiling, which allow techs to slide the gear into just the right place for any species that arrives for an examination. Whether they're large or small, if they like to perch or need a hole to hide in, the exam rooms and holding areas have flexibility to accommodate almost everyone.

The biggest creatures, elephants and rhinos, still get house calls. Anyone under 1,000 pounds gets a trip to the doctor's office.

"One of the really big challenges was making it so that it works for as many animals at the zoo as possible, which is anything from a little tiny gecko to, like, a camel," architect Dominic Weilminster said. "When we started this process, we visited what the vet staff thought were the best, newest hospitals or the standard bearers nationwide."

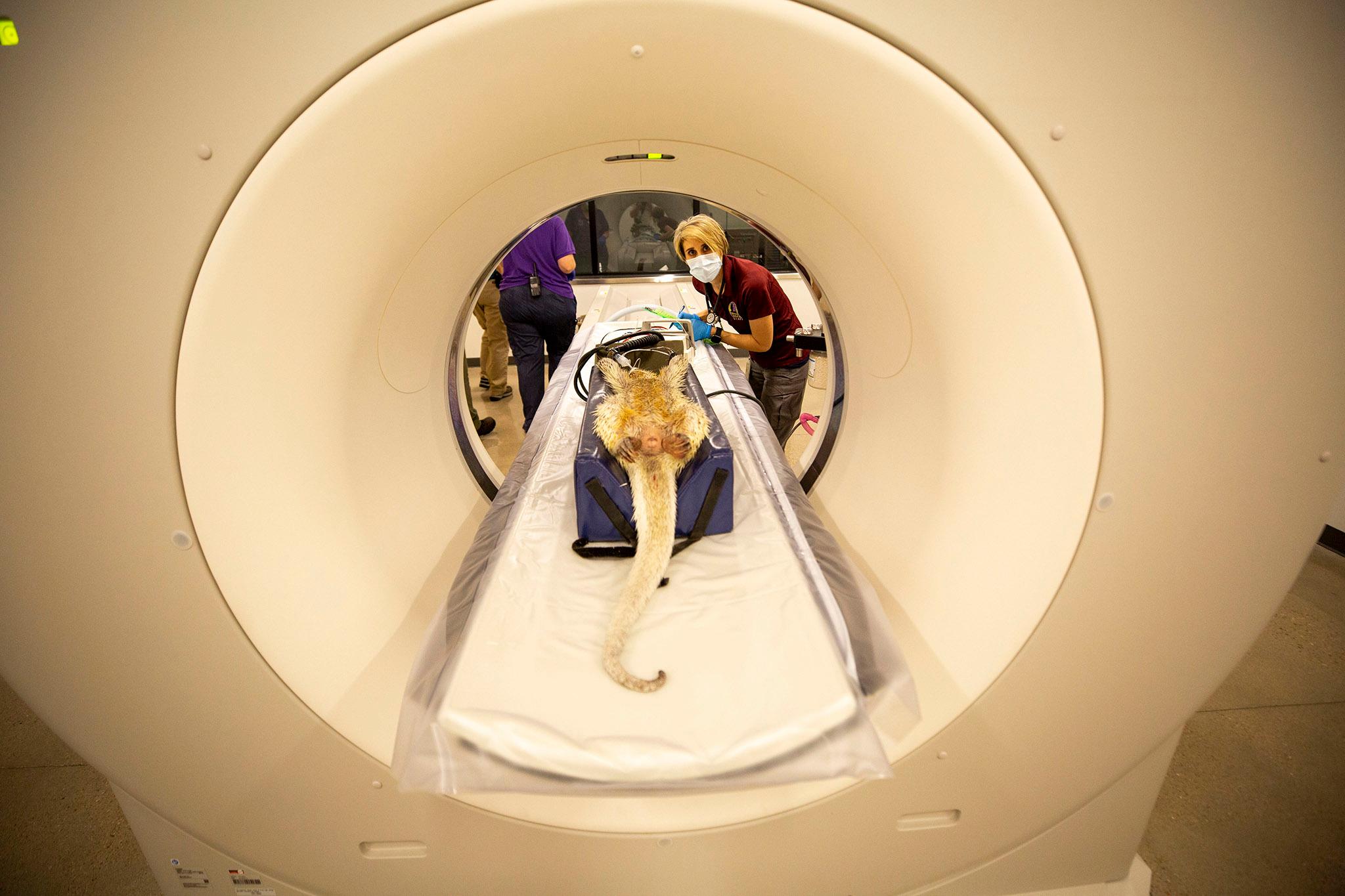

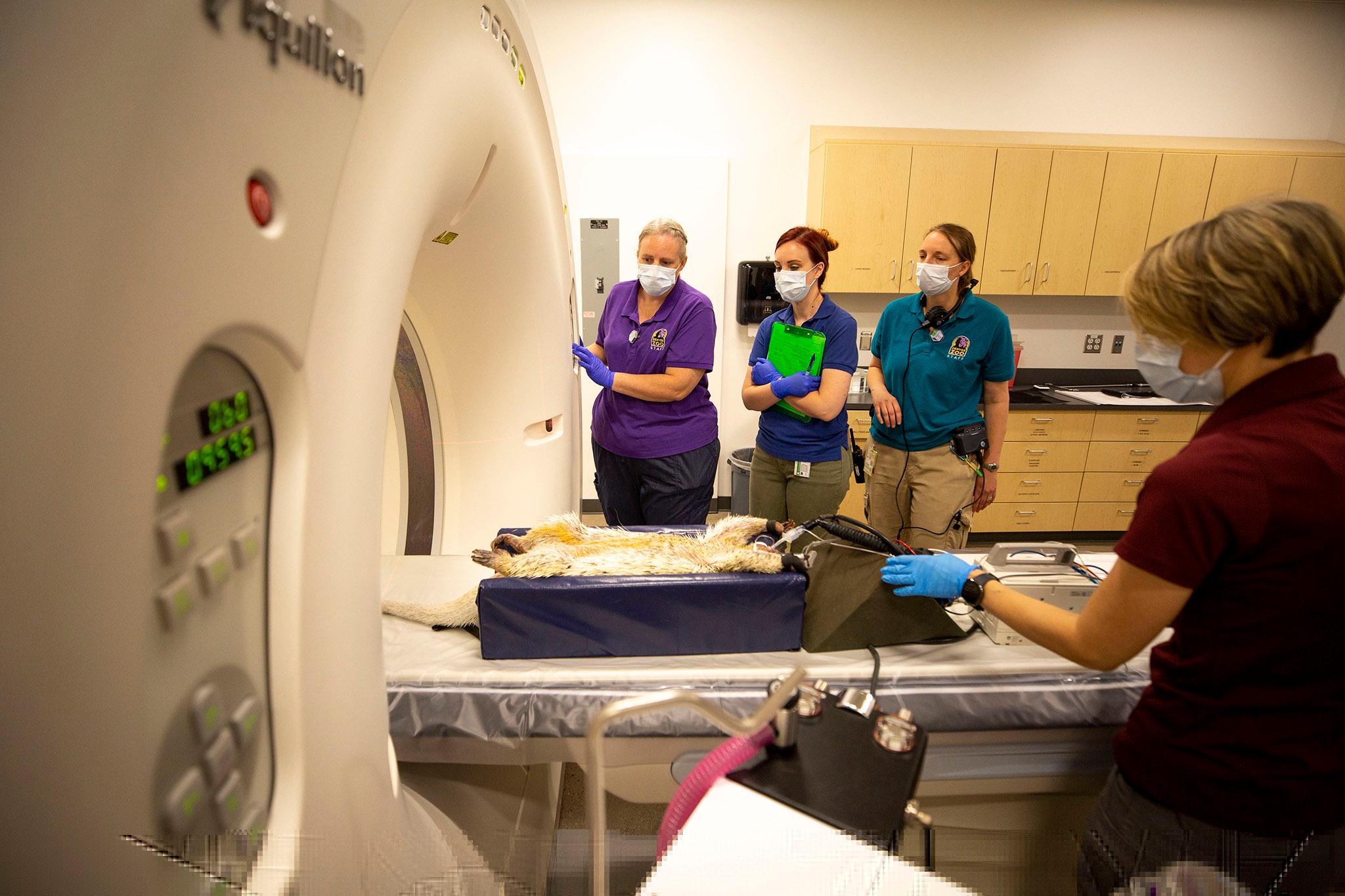

One major new feature is a massive CT scanner, the biggest on the market, that's allowed veterinarians to overhaul their diagnostic approach. There was a time when they needed to outsource this kind of tech, and they could only do it a few times a year.

"We used to even take animals offsite, in some cases to human medical facilities," Jake Kubie, spokesperson for the zoo, told us. "I watched a 400 pound orang get wheeled into National Jewish."

Zoo vets had access to this kind of equipment just five or six times a year before the new hospital. Now, Croft said, they hit five scans every few weeks.

"It's really allowing us to elevate our level of care and our diagnostic capabilities," she said. "It's pretty cool."

The scanner was useful for Koko, whose stomach stone didn't appear on regular x-rays. It lit up in the display after the machine carried her into its field of view.

This may be a golden era for zoo doctors.

It wasn't long ago, Dr. Jennifer Hausmann told us, that illness among zoo patients was often a dead end. Conditions vets regularly treat today might have been reason to euthanize animals thirty years ago.

"As we figure out how we can do more things, we're pushing that limit again and again. So we're doing chemotherapy for our patients now. We're doing more scoping, more surgeries, plasma transfusions," she said. "We've learned so much more that we are pushing that, to try to match everything they can do in even the human field or the domesticated field."

Open-abdominal surgery for even the tiniest of lizards is now something that actually happens at the zoo. And right now, Hausmann said, there are so many new advances in zoo veterinary care that she and her colleagues regularly publish case studies to share both successes and failures with colleagues across the globe.

Pushing the envelope is important, Hausmann said, "to be able to provide the best care for our animals so that they can have a healthy, happy life here and teach all these children to care about the animals and, hopefully, care about their counterparts in the wild and want to save them."

This work may seem kind of esoteric, the kind of thing that only affects animals living in captivity. But Croft said a deeper understanding of illness within animals at zoos is informing studies in wild ecosystems. Denver Zoo vets contributed research on "interocular pressures" in frog species, which she said may help scientists understand disease in amphibians living in a place like Lake Titicaca, on the border between Peru and Bolivia, where the Denver Zoo has funded research projects.

"Amphibians around the world are in peril, so understanding what contributes to that - whether it's increased UV and things that we're doing to their habitats - may help inform decisions for management," she said.

But zoos haven't always been such centers of care and learning. Kubie said it's something the Denver Zoo has had to reckon with as it dug into its archives for its 125th anniversary, which it's celebrating this year.

"It wasn't always great. We've got pictures of bears tied up to trees in a cage," he said. "Obviously we're lightyears ahead of that."

Better care means zoo animals are living longer. Still, difficult decisions are inevitable.

There's no exam schedule for visitors to plan their visits around because the work in this hospital is always fluid. Even in the absence of medical emergencies, vets constantly shift their caseloads around to see patients who need care first.

And there isn't necessarily one person who gets to make decisions on animal's care plans.

"We try to do it collaboratively, between the vet staff and the animal staff, because caring for these animals, it really is a combined effort," Hausmann said. "The keepers are the first lines of defense; they work with these animals every day, so they know very early on if something is off because they can see the change in subtle behaviors and they let us know. Then we do a procedure to find out why."

This collaboration was on full display as Koko's caretakers huddled with doctors and techs over an endoscope monitor. They'd found the bile stone, and a camera inserted into her esophagus confirmed it was wreaking havoc on her stomach lining. But there was a problem: The stone was too large to pull out through her throat. Surgery wasn't an option - the procedure would likely cause more harm than good. They spoke quietly, even though the children watching through the windows couldn't hear them. They'd have to discuss other options.

"We do employ every technique that we have available to us, between pain meds, acupuncture, physical therapy - which is more for those old geriatrics with arthritis," Hausmann said. "Because they get good vet care, we do have a lot of geriatrics."

Moments like this can be tough for the staff. The keepers know these animals well, their habits and their personalities. The vets strongly believe in "doing no harm." Sometimes that means making a hard choice.

The mantra around here, Hausmann told us, is to ensure that animals' "last day is not their worst day." In that spirit, Koko's caretakers and doctors decided together it was time to say goodbye.

"When we get to a certain point that we feel we cannot provide them a good quality of life, and we know that they're in discomfort, we usually do elect to euthanize," Hausmann said, "to end any suffering that is occurring in as peaceful a manner as we can."