It's the first day of school at Robert F. Smith STEAM Academy and Jessie Matthews isn't excited about his electives.

"Choir?" he balks.

Don't worry, an administrator tells him, he'll have a chance to change classes in a couple of days. Then his mother, Carmen, herds him and his friends against a wall. She makes them pose for a few last photos before they wander into the building for the first time.

Matthews is part of the high school's inaugural class, a group exclusively made up of 9th graders who will begin a curriculum never seen before in Denver Public Schools. Smith Academy was set up specifically to help students of color achieve in school by mirroring experiences they might find at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (or HBCUs).

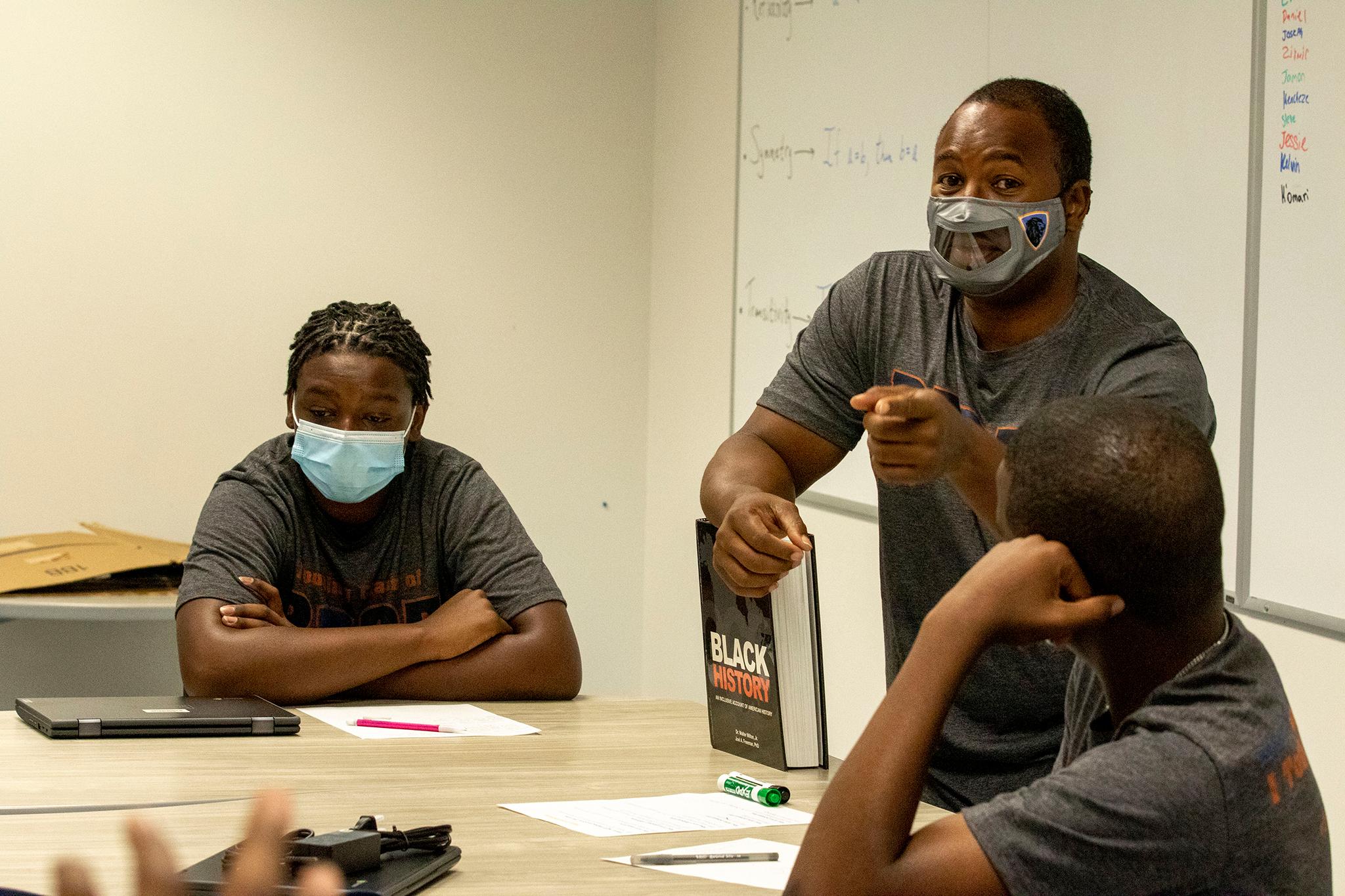

Principal Shakira Abney-Wisdom said she and her colleagues based their lessons on Black History 365, a curriculum meant to infuse stories about people of color in every class they offer. She also said her administration is working on partnerships with HBCUs to facilitate connections between her students and college alumni, both to provide academic support and establish "intergenerational relationships" in students' formative years. All of this, she told us, is meant to erase systemic obstacles that these students might face elsewhere.

"There is a persistent erasure of the Black experience, of Latinx and indigenous experiences in this nation and world. Our focus is to really center the experience of those of us who have been marginalized and minoritized. We are not, by nature of our existence, 'less than.' But our stories have not been valued in the same ways," Abney-Wisdom said as she paused for a moment in the hallway. "Our school's existence is just an act of resilience and resistance to oppressive structures in society. This is a sanctuary, really, a safe space for our scholars to be all that they are, and to grow, to challenge themselves, to challenge one another, to accomplish the goals that they have."

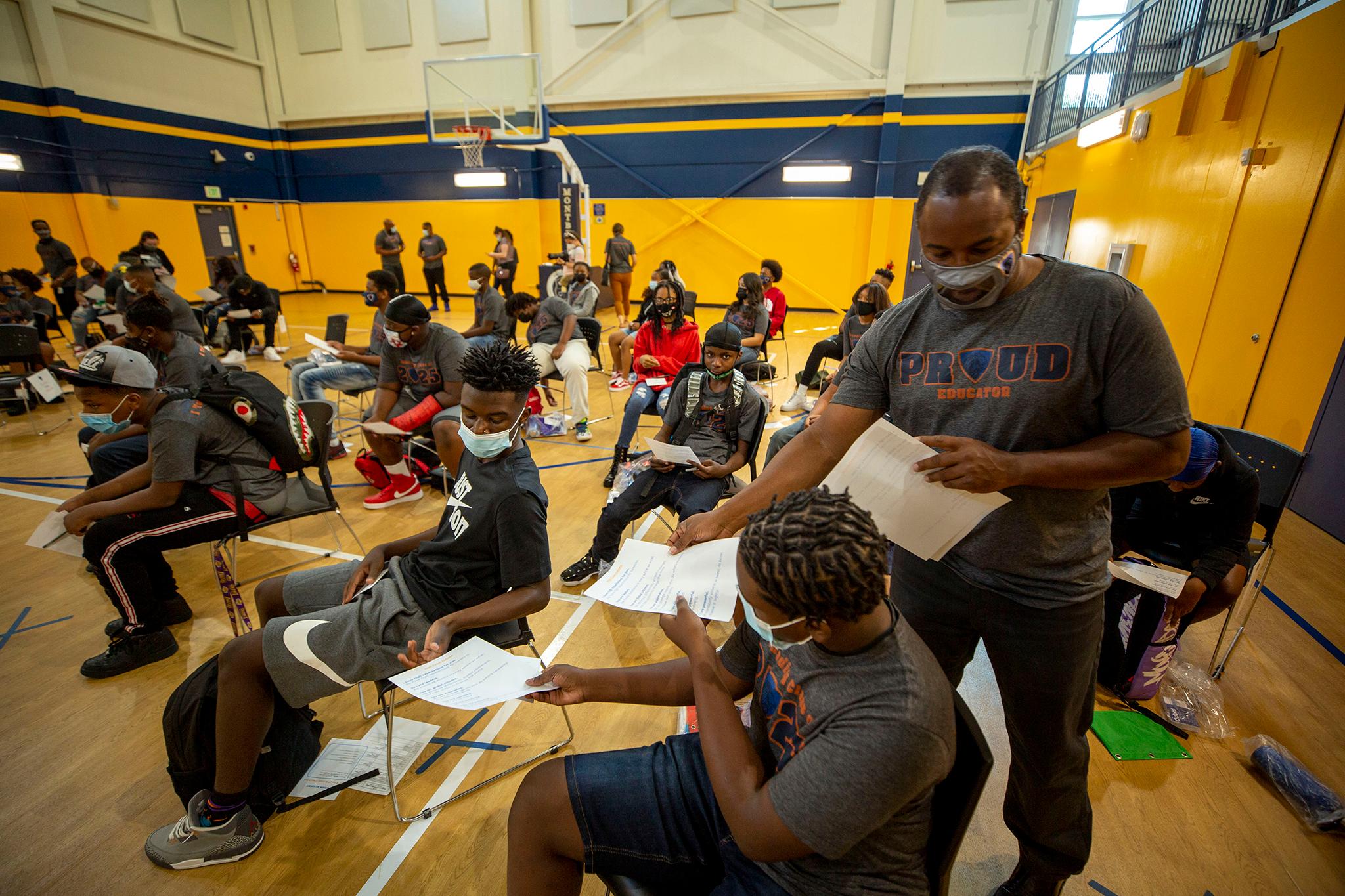

Before introductory classes began, Abney-Wisdom gathered all of her new students in the gym. She made sure everyone knew they were here to chase excellence.

"I have high expectations for you," she shouted to the room.

"We have high expectations for ourselves," they boomed back.

Smith Academy sits in the middle of "far northeast" Denver, which has long been embroiled in conflicts over education.

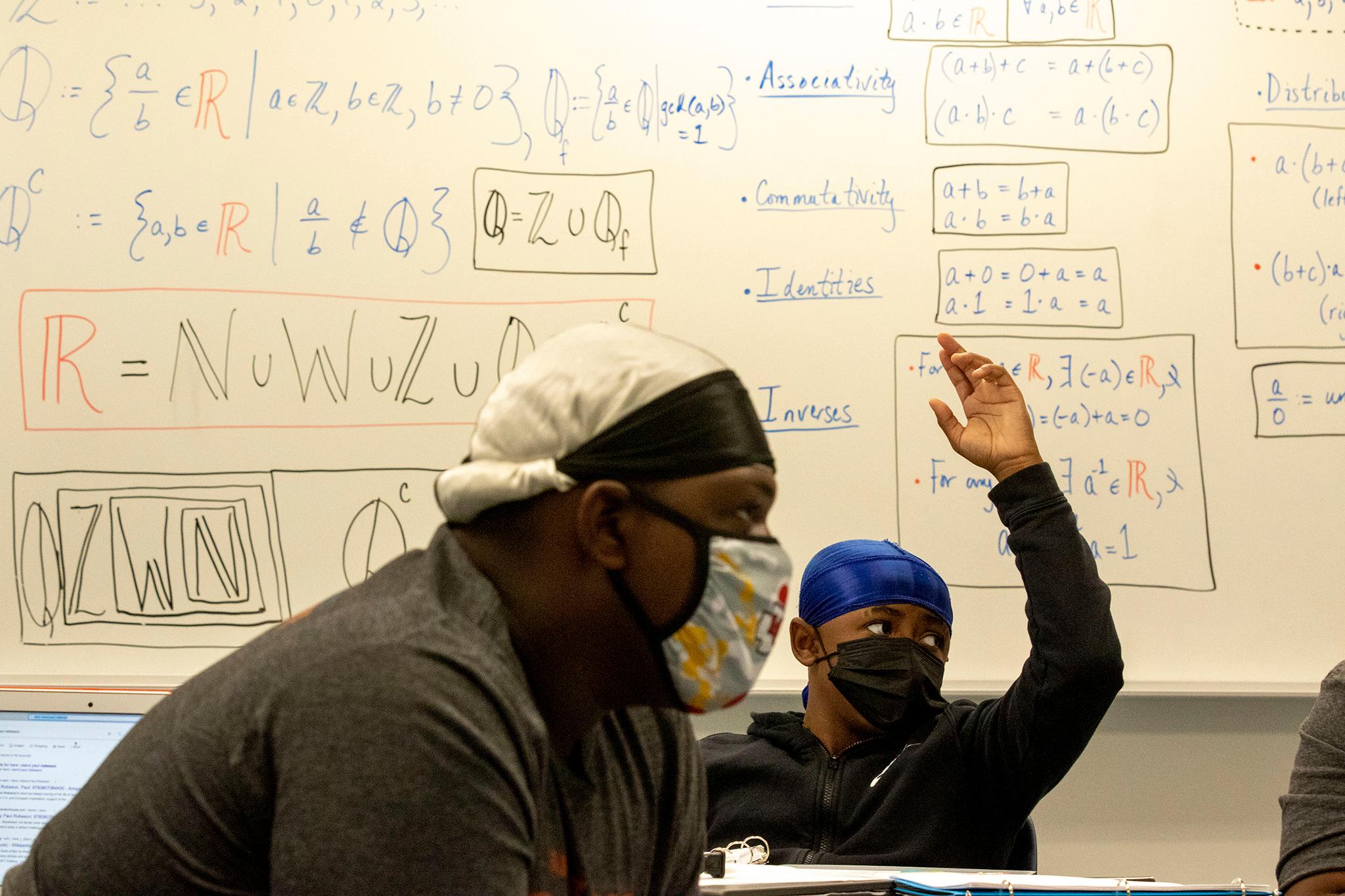

After the assembly, Matthews settled in with his homeroom class - they're called "prides" at Smith, because their mascot is a lion - and listened as his instructor introduced himself. Najja Shakir Al-Islam is a math Ph.D who decided to focus on teaching high school kids. After some icebreakers, he asked if any students had any questions for him. Matthews raised his hand.

"Why did you decide to come and teach here?" he asked.

"Because I love you," Al-Islam responded to the classroom of Black boys, not missing a beat.

"The way that we've been cordoned off as a group, most of us come from the same ethnic line, meaning that the chances of your great grandparents being chattel slaves is really high," he told them. "So all of us share that. Just because of that, I have to love. Because if I don't, if your elders don't love you, how are you going forward in life?"

This is the kind of environment Smith Academy's founders felt they needed in the city's northeast corner, which is home to many residents of color. The new school shares a glass-walled building in an industrial park with the Montbello Career and Technical High School, just between Montbello to the west and Green Valley Ranch to the east. Equity in education has long been a topic of discussion here.

The neighborhoods haven't had a comprehensive high school in a decade. In 2010, Colorado's Department of Education identified Montbello High School as one of the lowest-performing schools in the state. Denver Public School's board agreed to shutter it as a result. While some parents have been happy with the collection of charters and smaller schools that have sprung up in Montbello High's place, many people who lived in the area ten years ago saw its closure as a blow to these neighborhoods' very social fabric.

Samantha Pryor, one of Smith's co-founders, was one of those long-time residents who felt like something needed to be done.

"We wanted to create a high quality option in our neighborhood, because a lot of our kids were going outside of our neighborhood, traveling long distances across the city, to find quality options," she said.

The school's name, Pryor said, was their second choice. She and her colleagues first tried to name the school after Michelle Obama, but the former first lady's foundation politely declined their request. But "Robert F. Smith" still evokes the high level of achievement that they hoped to communicate. Smith, who grew up in Denver, worked as a chemical engineer and investor on his way to becoming the richest Black man in America. In 2019, he famously announced he would pay off all tuition debts for the graduating class at Morehouse College, an HBCU in Atlanta.

Pryor and her fellow co-founders - her husband, Brandon Pryor, and Gabe Lindsay, who both coach the football team that pulls from all of the high schools in the area - were also deeply involved in an effort to resurrect Montbello High. In February, the Denver Public Schools board voted unanimously to do just that. The school will reopen in its old space in 2022.

Lindsay told us both Smith Academy and a revitalized Montbello High are needed right now.

"It wasn't 'either or.' It was both, because both fill a gap that's needed in our community," he said.

Smith Academy, Brandon Pryor added, provides an outlet for smart kids who want to be challenged while Montbello will offer a "community option" that might once again stand as a social and civic center in these neighborhoods.

Matthews' mother, Carmen, graduated from Montbello High before it closed in 2010. While she said it was a painful moment for her neighborhood, she prefers not to dwell on the past. Instead, she said she's saved her energy to support efforts that will pave a better future.

"When this opportunity came about for our children, it was something that we just couldn't pass up. We think that coming to Robert F. Smith STEAM Academy is going to give them what they need to have a good sense of self," she told us. "We have to let our children know that it's important, and we want others to come and be a part of it. It is a wonderful community that's had a very bad rap for so many

years."

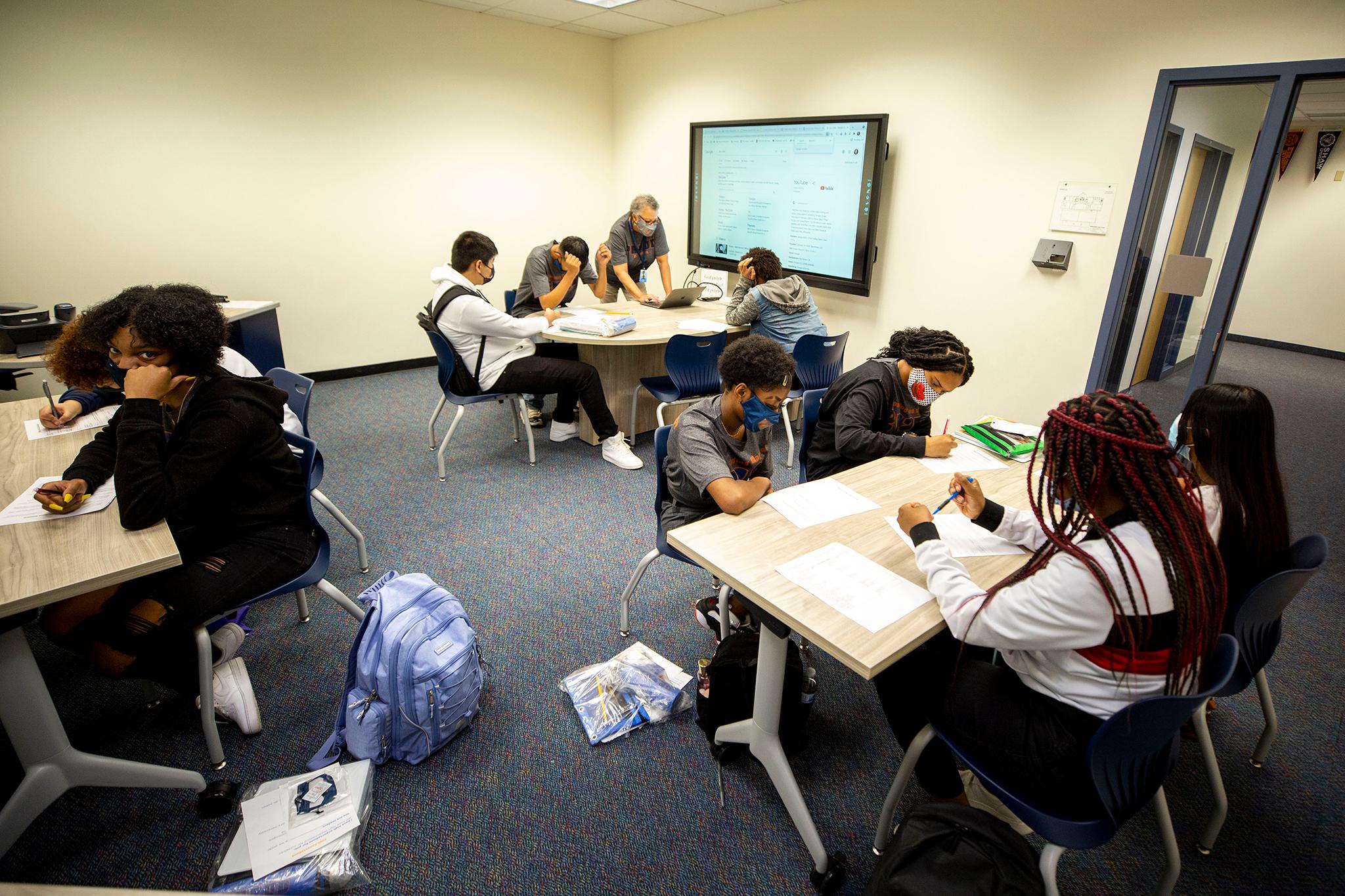

The students were excited, if not a little anxious.

It wasn't the high-achieving standards that had some kids feeling jittery. More so: many just hadn't been in a classroom in a very long time.

"I'm nervous because I haven't been in a school building in a year and a half," Alexis Weddington told us as the first day began. On the other hand, she was looking forward to seeing classmates again: "I like staying at home, but then it's like, I like getting to know people."

Emmanuel Paris said his mother attended an HBCU, so that's where his eyes are set four years from now. He said "everything, honestly," about the school attracted him to Smith Academy's inaugural class, but he and his parents most liked the idea that Smith Academy could set him on a track towards the kind of college he wants to attend.

And Aza'rayah Shorty said she was most looking forward to "the fact that we don't have to wear uniforms," though the academic possibilities are a big deal to her too. She plans to be the first member of her family to go to college.

Principal Abney-Wisdom, an HBCU graduate herself, lingered in the hall as her students found their way to their new teachers.

"I joined the work in June of 2020, and so it's been exciting to go from being the only staff member on the school-based team to then recruiting nationally and internationally for our educator positions," she said. "And now they're here. So it's really surreal and special."