Denverite fan Charlie Earle noticed a ring of old homes around a big, green lawn as he was driving out of southwest Denver recently. He wanted to know more about them so, naturally, he asked us to dig in.

The short answer: The Victorian houses Earle spied from Quincy Avenue and Lowell Boulevard, right on the city's border with Englewood, were some of the first structures built at the Fort Logan army base after Congress authorized its formation in 1887. They were home to officers until at least World War II when the military began to phase out the site and replaced it with a Veterans Affairs hospital. One famous resident was a pre-presidential Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In the 1960s, the Army sold the land to the state of Colorado, which converted many of the remaining buildings into mental health and addiction treatment centers that are still in use today. But one home became dedicated to the history of Fort Logan, and that's where we found a story that goes far beyond the built environment here.

Winnie Burdan wants you to know that women were always part of American military history.

The home set aside for posterity is now the Fort Logan Field Officer's Quarters Museum. That's where we met Burdan. She's greeted guests and given room-to-room tours for years. The volunteer gig fits right in her areas of expertise: she's a history buff and a veteran herself.

After she graduated from nursing school in the 1950s, Burdan joined the U.S. Air Force and served stateside during the Korean War. Her husband was also in the military, and after she left the service she and their six kids moved around the country with him as he took new posts.

Burdan always loved visiting historic sites when they arrived on a new base. But over time, she started to realize something was missing everywhere she went.

"I never discovered any pictures or any mention of any wives or children," she told us. "Over the years, it really upset me, because people just saw men."

When Burdan and her husband decided to retire and settle down permanently, they chose Denver by (literally) throwing a dart at a map. After she'd gotten her bearings here, a friend suggested she go visit Fort Logan's museum. That's when she saw an opportunity to correct the historical record.

Burdan has become the museum's specialist in women's history. While most people just stop in to see old furniture and uniforms, she's worked to expand the range of stories represented in the space and does her best to remind visitors about the mothers, wives and families that are central to Fort Logan's early story.

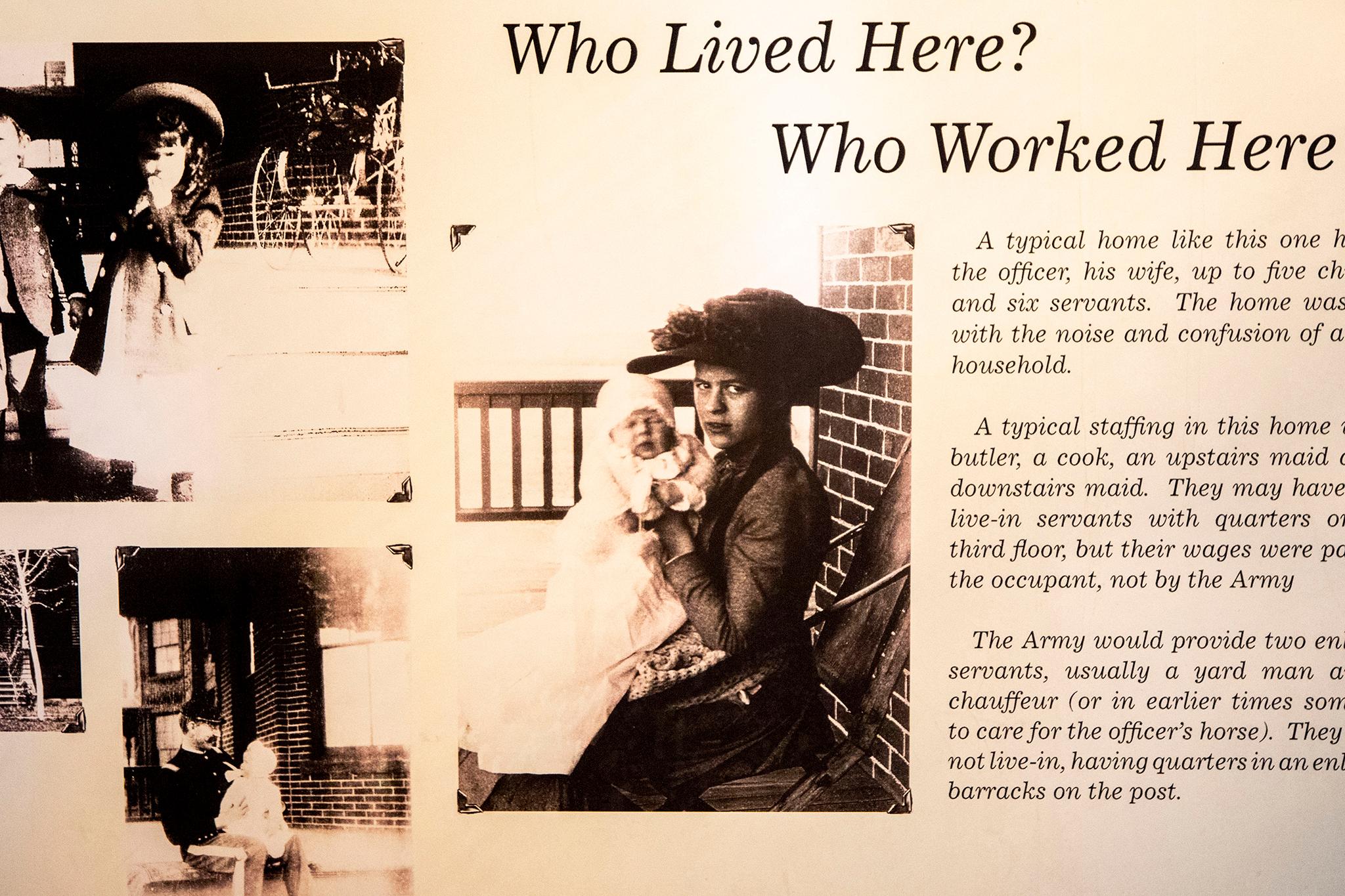

While women couldn't openly serve in the military until World War I, they accompanied and supported troops as far back as the American Revolution. In Denver, officers brought their families with them as they moved into Fort Logan in the late 1800s, then left them there as they pursued campaigns against Native Americans who were still fighting to remain on their ancestral lands.

"They lived for months without their husbands at these forts, and they were remarkable women," Burdan said. "They had a very hard life because there was a lot of dysentery and the water wasn't good and they ran out of food."

Some held jobs on base where they managed money, laundered clothes or cooked.

Burdan said the lifestyle was initially an adjustment to many of the officers' wives, who came from upper-crust enclaves in the East and suddenly found themselves in a place with fewer social norms. On one hand, they dealt with "a big shock to their self-esteem" when they realized they needed to mix with lower-class women to survive. On the other, Burdan said they found "complete freedom" in their new lives and soon embraced friendships with the lower-class women around them.

"It opened a whole new world to them," Burdan said. "It was a marvelous experience for them because their prejudices flew out the window. They couldn't be prejudiced to the woman who delivered their babies."

Fort Logan's women were integral to the base's operations and the army's success then and now, Burdan said. She sees herself in them, both as a military wife and as a nurse who supported service members in the '50s.

Some even became crucial to their male counterparts' legacies, like Una Merriam, wife to Henry Clay Merriam, Fort Logan's first commanding officer.

According to Burdan, Henry was a Civil War hero who led a battalion to victory in Alabama on the day Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House. His accomplishment was buried by the bigger news of the day. Years later, Una lobbied the federal government to recognize her husband as a brigadier general, which they did in 1897.

Today, Henry's photo hangs on the wall of the museum, the home he and Una moved into when they arrived in Denver. Though Henry's name is attached to the house, Merriam said he wouldn't have lasted long without Una to back him up.

Now for something completely different:

Here's something worth a few extra sentences. In addition to housing people, Fort Logan was also home to some U.S. Army "war balloons" that were used for reconnaissance in the Spanish-American War. A balloon bay used to sit somewhere on the grounds, though it was demolished a long time ago and nobody at the museum is exactly sure where.

Sue Ewing, who works there with Burdan, said one of Fort's airships was used over Cuba before its aeronaut flew too close to enemy troops and was shot down. It turns out balloons are big targets that are particularly vulnerable to bullets.

The Field Officer's Quarters Museum is open on the third Saturday of each month (except December) from 1 to 4 p.m.