Earlier this month, it snowed for the first time in 232 days, breaking a city record for days without snow. We're now in the second half of December and have yet to see a major storm. As the weeks go by without Denver breaking a half-inch of monthly precipitation, we're starting to see more talk about drought -- its causes, severity and long-term implications.

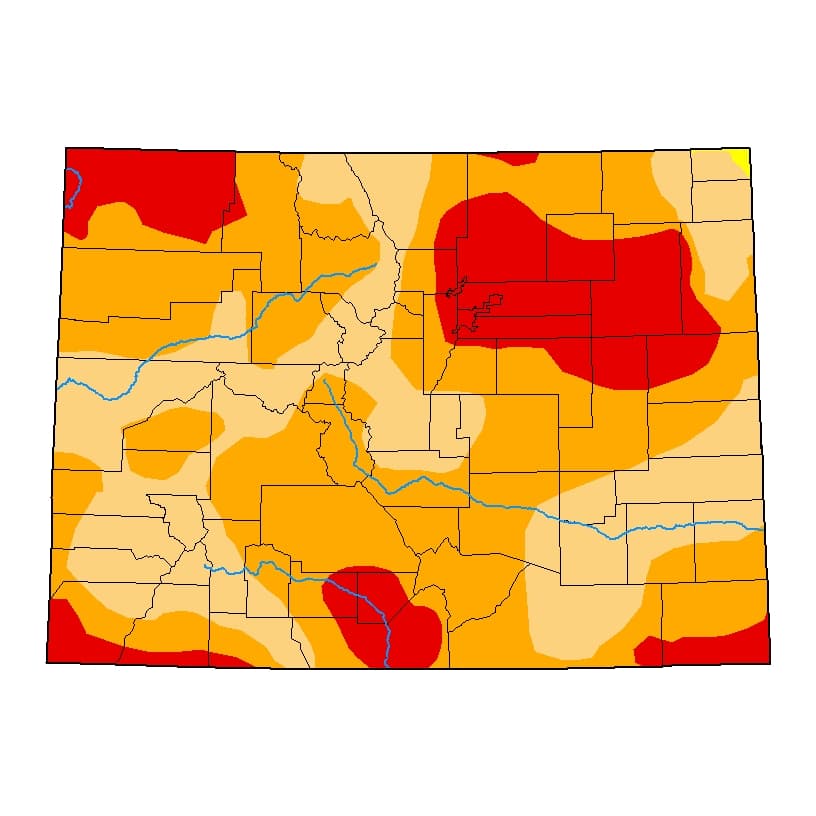

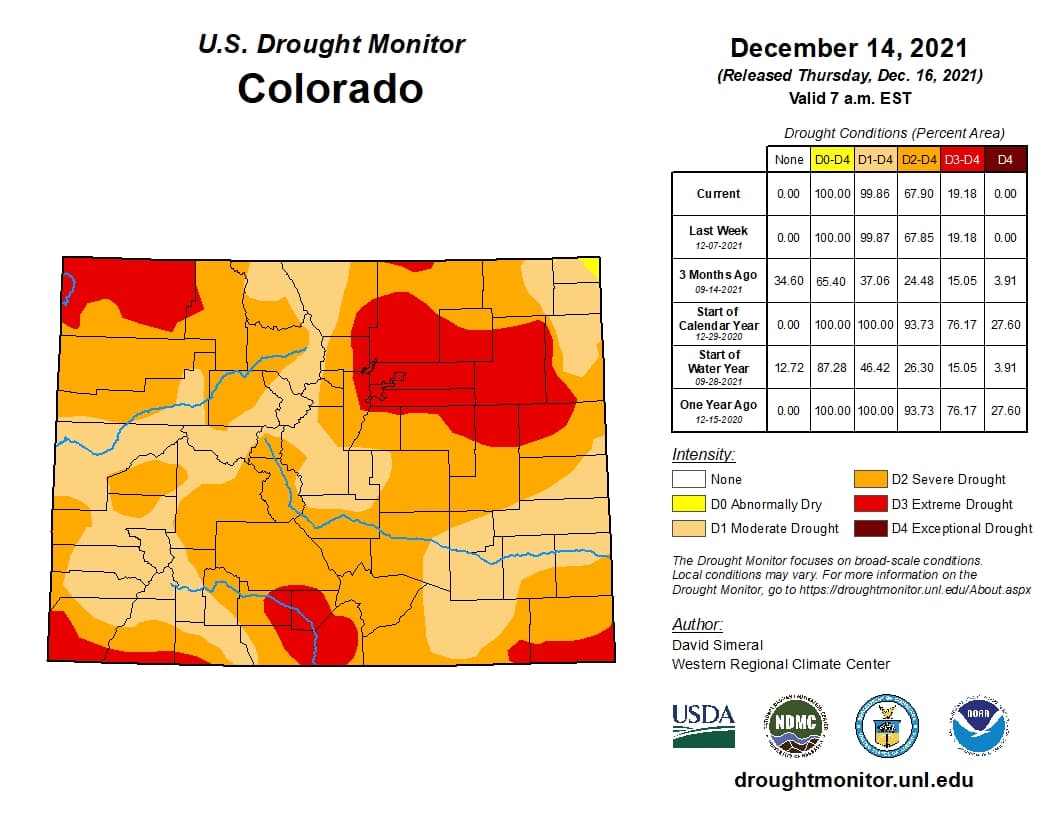

In early December, Denver's drought graduated from "severe" to "extreme" on the U.S. Drought Monitor, a national service that tracks drought conditions across the country. What does an "extreme" drought look like? What does it mean for people living in Denver? And at what stage of a drought does Denver Water decide to implement water-use restrictions?

We talked to some climate and water experts to find out how they categorize droughts, how concerned we should be about this one, and what it means for people living in Denver. Here's what they told us.

Denver is in a drought. What does that mean, exactly?

Drought is defined (pretty vaguely) as an extended period of relatively low precipitation in an area. But there's a lot more that goes into how local and national organizations categorize drought.

"When we think about drought, drought is really multifaceted," said Peter Goble, a service climatologist for the Colorado Climate Center, a state office that assesses decades of drought-related records gathered at stations across Colorado.

There are several different kinds of drought.

"You could be talking about just simply a meteorological drought, which is probably the most simple definition of, 'It's raining a lot less than normal.' Or, 'It's a lot warmer than normal, and we're losing water more quickly,'" Goble said. "Oftentimes, when people think about drought around here, we think hydrological drought, which is, 'What's the state of our water resources? What do our reservoirs look like?'"

There's also agricultural drought, which is a reflection of a drought's impact on agriculture in a region, and socioeconomic drought, which is when drought impacts the exchange of goods and services in a region, like if ski towns suffer from reduced tourism because of low snowpack.

On Dec. 16, the National Weather Service reported that since July 1, Denver has been the warmest and driest it's been on record.

"When we see statistics like that, we kind of have to recognize that as a meteorological drought," Goble said.

That categorization, he said, reflects the breadth of the drought: how many sectors are affected, and how widespread its impact is. The U.S. Drought Monitor, meanwhile, reflects how severe the drought itself is.

The U.S. Drought Monitor is updated and released every other Thursday by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The map shows which areas of the U.S. are experiencing drought and, using five classifications, how severe the drought is in those areas.

David Simeral works for the Western Regional Climate Center in Nevada and is one of ten authors of the U.S. Drought Monitor.

"Whoever is the respective author for the week is the lead person who does all the drought analysis and coordination with all the various state and regional level drought coordination teams," Simeral said.

The authors examine quantitative data provided by local and regional groups across the country, like the Colorado Climate Center. The data includes dozens of indicators like temperature and precipitation, soil moisture, streamflow levels, groundwater levels, reservoir levels, and snowpack conditions, as well as related factors like vegetative health, fire danger, and evaporative demand, which Simeral called the "thirst" of the atmosphere resulting from conditions like high temperatures and strong winds.

The map's authors assess these different indicators and present them as percentile rankings, based on where they rank in the history of recorded data for that region. The authors converge all of this evidence, and based on where the majority of the indicators are pointing, give the region a classification.

"That's a snapshot of drought, right now in time. That's the current situation," Simeral said. "Basically, what we're trying to capture is the magnitude of the drought, which is kind of the duration of the drought, plus the intensity of it."

There are five different drought classifications:

- D0 (Abnormally Dry)

- D1 (Moderate Drought)

- D2 (Severe Drought)

- D3 (Extreme Drought)

- D4 (Exceptional Drought)

As of Dec. 2, Denver Country is in "extreme drought". In extreme drought, the evidence put us in the third to fifth percentile of drought severity in Denver County's history.

While this is an "extreme" drought, drought itself is nothing new in Denver.

"If you look at a time series graph of drought in Colorado, you have basically been in and out of drought in Colorado since almost 2000," Simeral said.

He said that's in large part due to low snowpack and warmer temperatures than normal, which all leads to premature melting of the snowpack in the mountains.

Still, Denver is in a period of concerningly low rainfall.

"Looking at the autumn, the October through November period and the September through November period of two and three month periods were the driest on record for Denver County," Simeral said.

Goble said a huge part of the deficit is that we haven't had the "right ingredients" to produce the big storms.

"We've seen an anomalous amount of high pressure atmospheric conditions. When we're under a high pressure system, that's when air is calm and generally sinking rather than rising. And that's not conducive to producing moisture," Goble said.

Todd Hartman is a spokesperson for Denver Water. He said there's hope for bigger storms in the new year.

"Big storms can really be game changers. We've seen that over the last decade, several times," Hartman said. "You get a lot of storms throughout the fall in the winter and early spring. About 80% of our snowpack tends to come from only 20% of the storms. So we do look for these bigger events to help us, which is why even though things are not great right now, we still have some hope that they'll improve."

What does this drought actually mean for me as a Denverite?

Drought categorizations mean different things for different states. According to the Drought Monitor, in Colorado, a D3 (Extreme Drought) categorization can mean:

- Worsened pasture conditions

- Dying city landscapes

- Large fires

- Recreational activities like rafting, fishing, hunting and skiing are reduced, and fish kills occur

- Notable insect infestation, particularly grasshoppers

- Reservoirs extremely low; water restrictions implemented; water temperature increases

However, not all of these conditions necessarily apply in Denver County, especially because our water supply comes from outside of the city.

"Calling this an extreme drought for the Denver area, even if it's the driest that we've been on record over the last six months or so, during the winter when we don't really see the impacts, it can be confusing from a communication and public relations-type standpoint," Goble said.

Simeral said the drought might impact recreation, like the ski season and rafting outfitters. It can have ecological impacts. Warm waters can lead to higher mortality in trout populations, which further impacts fly-fishers. Extreme drought may negatively impact agriculture in the plains.

"In terms of actual impacts on the ground in Denver itself, I don't think you're going to really see a whole lot in terms of what somebody is going to feel in their day-to-day life," Simeral said.

Most of the water we use doesn't come from Denver County itself. Denver Water services about 1.5 million people in the Denver area. Its collection system spans thousands of miles, and includes 12 to 20 reservoirs fed mostly by snowpack in the mountains, which have seen more precipitation than Denver. For now, the reservoirs Denver depends on for water supplies are in decent shape (for example, Simeral said, Dillon reservoir is 78% full at the moment).

"That's both due to good management on the part of Denver Water, but also, the water that we use in the Denver area is more a function of what happens in the mountains than what happens locally," Goble said. "So from a hydrologic standpoint, we may not feel the effects of a local meteorological drought right away, if at all."

There are also seasonal factors. Hartman said we tend to use significantly more water in the summer than in the winter, due to outdoor water use like lawn maintenance.

"This is our lowest water use period here, late December into January," Hartman said. "So the day-to-day effects on people is pretty limited."

Hartman added that the South Platte River Basin, which is where Denver gets about half of its water, is still quite a bit below average supply levels. That said, there's still time for the big storms to hit, as they did last spring.

"We have time to turn that around," Hartman said. "So while we're concerned, we're still hopeful."

Denver Water has a process in place for determining when to call for water-use restrictions.

Should we face a water shortage, the Denver Water Board of Water Commissioners may make a decision to implement water-use restrictions. But right now, Hartman says it's too soon to call for water restrictions, or even to say whether they will be necessary.

In the coming weeks, Denver Water will continue to monitor water supply levels. If things don't improve, Denver Water may begin talking to the public about drought conditions and recommending that Denverites voluntarily dial back their water use.

If we don't see those game-changing big storms, Denver Water would consider gradually implementing mandatory water restrictions. Those would begin with some of the more familiar restrictions around outdoor water use, like setting designated hours for lawn watering or limiting the number of times Denverites can water lawns in a week.

If drought conditions worsen still, Denver Water may consider eliminating outdoor water use altogether, with certain exceptions and exemptions. Only after those stages would it consider some indoor water rationing.

You can read more about Denver Water's Drought Response plan here.

How you can help.

"I do like to say, it's always good to use water wisely," Goble said. He says the summer is when people can make the most difference. "Where most people could save a lot more is outdoor watering type usage."

Still, Hartman says there are small things you can do in the winter and year round that make a collective difference.

"Just turn the faucet off when you're using it, when you're brushing your teeth and shaving," Hartman said.

He said you can also check for leaks and replace older toilets with ones that use less water.

"These are really no-brainer behavior changes that people can make, that if made across a lot of people saves a lot of water," he said. "Even though it doesn't sound very interesting or sexy, simple things like that are really important."