In 2019, construction ended on a project that would fill one of the last undeveloped areas in downtown. The Coloradan, a 19-story condominium building on Wewatta Street, offers 334 mostly high-end units starting in the high six figures.

Trendy restaurants and bars, a giant Whole Foods, and Union Station are within walking distance of The Coloradan. Its developer, East West Partners, claims on its website that the building is in one of the most desirable areas of the Union Station neighborhood, which is bordered by 20th Street, the South Platte River, Cherry Creek and Lawrence Street.

But three years after The Coloradan opened, its units are decreasing in property value in a city that's becoming costlier by the day. Residents are so fed up with what they view as the cause -- crime, homelessness and drug use in the streets below -- that some have organized into the Safe, Clean and Compassionate Committee of the Lower Downtown Neighborhood Association. The subcommittee of the registered neighborhood organization advocates for, among other things, more law and order. The group is at odds with the area's representative on City Council, Candi CdeBaca, who once proposed replacing the police department with a "Peacekeeping Department."

The seemingly impossible question both sides are trying to answer: Since downtown is a hub of prosperity and poverty, who is it actually for?

"We're banishing the poor from the city," CdeBaca said. "And there's nowhere for them to go."

Many residents of The Coloradan were lured in by the glorious views and surrounding urban amenities.

When the building opened, the Denver Post reported two-bedrooms started at $805,000, and those with a den went up to $1.025 million.

While property values steadily rose, peaking in the summer of 2021, they have dropped over the past six months. A condo valued at $814,000 in July is now valued at about $775,000. For the residents who are scared of their neighborhood and are considering moving back to the suburbs, selling would mean losing money.

Among residents, "perhaps the biggest part of their personal financial portfolio is their real estate and ownership here," said David Mazzocchi, who bought units in The Coloradan but still lives in his home, in Golden. "Nobody wants to see that investment decrease in value."

But on the streets and in the bus terminal below, property value is the last thing many are worrying about, considering so few own a home or could even imagine doing so in this pricey city. Instead, as Denverites commute to work, go to the grocery store and eat at restaurants, others are having psychotic breaks, using drugs, and struggling to catch a few hours of uninterrupted sleep while being endlessly awakened by security guards. Many are searching for their next fix or escaping the cold after a night in a shelter.

And they're often doing so without basic necessities, like restrooms. After finding trace amounts of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, RTD closed the public restrooms at the bus terminal under Union Station. The restrooms in the Great Hall at Union Station are open, but only to customers of the restaurants and shops.

If drug users have nowhere safe to inject or smoke, they will do it in public, said Lisa Raville, who has spent over a decade working with drug users at the Harm Reduction Action Center, a day shelter, syringe exchange program and safe space for drug users.

Raville has long been an outspoken advocate for an overdose-prevention site in Denver -- a place where people can use drugs under medical supervision and out of the public eye, which would both minimize public use and prevent overdoses.

"Right now, the bus terminal is a day shelter for those unhoused and a use-site," Raville said. "It's just not supervised. When folks are unhoused, they inject outside, in alleys, in parks, and in business bathrooms. They prioritize business bathrooms first for three reasons. First, they can close the door so cops don't come up on them. They make sure the larger public can't see them, and [they] have access to sterile water.

"When they can't do that in a bathroom, it's public," Raville continued. "Overdose prevention sites/supervised use sites take drug use -- injecting and smoking -- out of the public space and into a controlled environment."

Kam Donda moves between shelters, encampments and sleeping wherever he can find a place to rest, which is often in Union Station.

He said the neighborhood isn't dangerous compared to other parts of town and other cities, and that Union Station offers some semblance of safety for unhoused people and users.

Many people use drugs openly at the bus terminal because others nearby can revive them in case they overdose, he said. But as a user himself, he's sympathetic to families who don't want to see people doing drugs while trying to catch a bus. That's one of the reasons he, too, supports a supervised-use site.

"Safe shooting rooms would be a huge thing," he said. "I know taxpayers ... most of them wouldn't necessarily be OK with paying for something like that. But on the flip side, if you look at it, your children won't experience [seeing drug use]. You won't see it yourself. You won't find so many needles or whatever on the ground, and the actual users themselves will have a safe place to do it. Maybe tie in some sort of safe smoking thing with it.

"I think it's kind of ridiculous to be walking with your kids or whatever and see somebody smoking drugs off foil," he continued. "That's not pleasant at all. But if they had a place to go do that safely, then maybe it would create a better environment for everybody."

Despite Denver's issues, there are reasons why it's often picked as a convention site, that big businesses move here, and that the city is consistently named one of the top places to live in the nation. The city offers ample retail, restaurants and cultural institutions to explore, all within a quick drive to the mountains.

That's what attracted homebuyers like Mazzocchi to The Coloradan.

Mazzocchi worked in telecom before retiring last year. The city center was his home away from home. Enamored with downtown, he bought his son and daughter condos at The Coloradan when they graduated from college.

"For both she and my son, it was basically a family investment to help them get started," he explained. "They're both young professionals. Both went to CU Boulder. In her case, she went to the Leeds School of Business down there. She has a wonderful job with a defense contractor. And, you know, we were excited about helping them launch in life and commingle with wonderful residents."

He began to worry for his 25-year-old daughter Lexi's safety when she was out walking her golden retriever, Henley.

"Every day we're getting phone calls," he said. Lexi would say, "You wouldn't believe what I saw today or my experience today or what this homeless person did to me or threw at me or yelled at me over here by that Whole Foods."

Lexi said she has had chicken nuggets thrown at her. People have called her names. Her car has been pelted by soda cans. Condo residents she knows have been followed to their apartments and threatened by strangers.

He bought his daughter a taser so she can protect herself.

Lexi said it's hard to keep her affable pup safe when there's so much trash on the streets, including aluminum foil used for smoking meth and fentanyl, and syringes.

"She's a puppy still. She puts everything in her mouth," Lexi said.

That includes discarded chicken bones and human waste. At the nearby dog park, she's heard of dogs eating drugs and getting high. An acquaintance's pet wound up with a syringe stuck in its leg.

Many of the people Lexi knows are Gen Zers and Millennials who moved to LoDo for the buzzing culture and dining scene.

"It's just kind of a hot spot to live in," she said. "It's hard because you hear from all these people. They're like, I can't take it anymore, living here with the exorbitant prices I pay and the safety that I'm not getting, that I don't feel -- especially in their own homes."

It's not just younger residents who are frustrated at The Coloradan. After retiring from long careers at NASA, Valin and Allyson Thorn moved from the suburbs to their downtown condo -- their first time living in an urban environment.

They came for the culture and walkability. Two years later, they're repulsed by the feces and disturbed by the needles and people sleeping in tents on the streets, smoking drugs in the Union Station bus terminal, and shouting at passersby.

At first, Valin felt pity for them. Now he feels anger when he hears about people refusing services offered by the city and is fearful of some people's erratic behavior and potential for violence. He has his concealed carry permit and said he will use lethal force to defend himself if necessary. He wants people breaking the law on the streets to be arrested, which would hopefully force them into treatment. When he goes shopping across the street at Whole Foods and sees people shoplift, he's baffled that nobody arrests them.

Police need more funding and public support, and he's ready to defend himself if he needs to, he said.

Valin said he comes from a working-class family that has experienced addiction. He's lost people he loves to drugs. And when he sees people outside breaking the law and using, he wants them to be forced into treatment by the criminal justice system.

If the Whole Foods across the street were to close, which Greenly said could happen, the Thorns would likely move.

"We are still here because we remain hopeful these crime problems are temporary," he said. "We would not stay just to avoid realizing a financial loss in the sale of our condo."

CdeBaca, who was a social worker before joining City Council, said the class tensions playing out in the area are symptoms of a larger economic problem and typical of a downtown in a large city.

The issue, as she sees it, isn't as simple as criminals running amok.

"The real issue is with unhoused people, mentally ill people and drug addiction," she said. "And that is a bunch of problems that are not just Denver's challenges. These are challenges across the country."

CdeBaca's frequent political rival Mayor Michael Hancock said as much during a press conference announcing a new crime prevention strategy on Feb. 2.

"This isn't just a Denver challenge, or a metro-area challenge, or even a Colorado challenge. It's an American challenge," he said. "There also isn't one singular cause for what we're seeing. Thus, no one singular or easy solution."

CdeBaca said central Denver has seen more unhoused people and crime than other parts of the city for decades.

"We experience a disproportionate amount of the burden because we're the downtown core," CdeBaca said. "This is how it is in most places, because services, businesses, transit -- it's all typically concentrated in the urban core."

Downtown is also one of the few places in Denver zoned for dense shelters, which means that pricey-condo owners share public space with unhoused people and others accessing social services.

She said downtown is for everyone: property owners, renters, unhoused people and tourists alike. That's the nature of cities. And just because a new condo has risen doesn't mean that the poor, unhoused or mentally ill or people who are addicted to drugs should disappear, she said.

Lori Greenly lives two blocks from The Coloradan. She's called Colorado home for the past 31 years and has worked downtown for most of that time. She moved to LoDo for the first time just over a year ago and has been appalled by the open drug use and crime. Nonetheless, she said downtown Denver continues to be on the rise.

"We're offering tens of millions of dollars of tax incentives to bring big companies here still," she said. "Denver as a whole isn't slowing down... You can't take away the quality of life that Denver offers. There's a reason companies want to move here."

She points to people leaving San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York and moving to Denver for cheaper living and more access to nature, a phenomenon that she said is not new.

"They naturally come here. After any downturn, Denver has seen a growth -- whether it was 9/11, whether it was 2008, whether it's COVID," she said. "So our economy is growing like crazy for a reason."

But if downtown is going to flourish, she believes the city needs to address homelessness and crime.

To advocate for her position, in October, she teamed up with Mazzocchi to co-chair the Safe, Clean and Compassionate Committee. They are asking for a more muscular police response to crime in the homeless population and for more frequent sweeps of encampments. They're recruiting other neighborhood organizations, like the Upper Downtown Neighborhood Association and the Golden Triangle, to get on board.

The group has grown from 10 founding members to over 180 active members. When combined with other neighborhood groups with like-minded platforms, Greenly said membership is about 2,000. Her email list includes 5,000 people, and her organization is in touch with 36 public officials and 20 journalists, she said.

The group has a particular distaste for CdeBaca. Their arguments: Politicians shouldn't coddle criminals and people who are addicted to drugs, but rather ramp up arrests and keep them locked behind bars. The public should distinguish between people experiencing homelessness who are down on their luck and need help and criminals.

Greenly said she believes safety has been going downhill since the push to defund the police, and it's time to celebrate law enforcement again. (Denver Police Department funding has actually increased overall since 2020.)

To push this platform, the neighbors are organizing community meetings with law enforcement, elected officials, political candidates and city agencies, including Denver District Attorney Beth McCann, State Rep. Alex Valdez and Republican gubernatorial candidate Heidi Ganahl.

Hancock, whose administration has been hearing regularly from Safe, Clean and Compassionate, responded to calls for increased safety from residents at the Feb. 2 press conference. He said addressing crime has become a priority.

"These are the stakes," he said. "Fentanyl is killing people on our streets. Right now. People are getting their hands on illegal guns, and they're shooting and killing people. Right now. Criminals are taking advantage of vulnerable individuals, and when we arrest them, they're getting right back out to do it all over again, right now in Denver, Colorado. Now, I'm not gonna allow this to continue to happen on my watch."

Safe, Clean and Compassionate isn't the only voice among registered neighborhood organizations vying for the attention of city leaders. A coalition of seven veteran RNOs and business improvement districts has been pushing a competing platform called the Unhoused Action Coalition.

That group includes political heavyweights like one of the oldest RNOs, Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods, powerful newcomer the RiNo Art District, the Baker Historic Neighborhood Association and Uptown on the Hill. CdeBaca said she finds inspiration in this group and counts many constituents as members.

The coalition has an unflinching awareness of safety concerns and the proliferation of encampments, but it takes into account the needs and issues facing the unhoused population, regardless of whether addiction or mental illness plays a role in their situation.

The group wants to see the city have a unified approach to addressing homelessness with more coordination between agencies and the Hancock administration; greater urgency from the Hancock administration and various agencies in addressing the rising amount of unhoused people; more energy, funding and neighborhood support for the Safe Outdoor Spaces program, along with more public space opened for similar temporary housing solutions. The coalition also supports tiny home villages and other creative housing strategies.

These RNOs also support Denver expanding its income-restricted housing. They advocate for more multiunit housing spread across the city's neighborhoods that are currently zoned for single-unit construction to address the housing crisis.

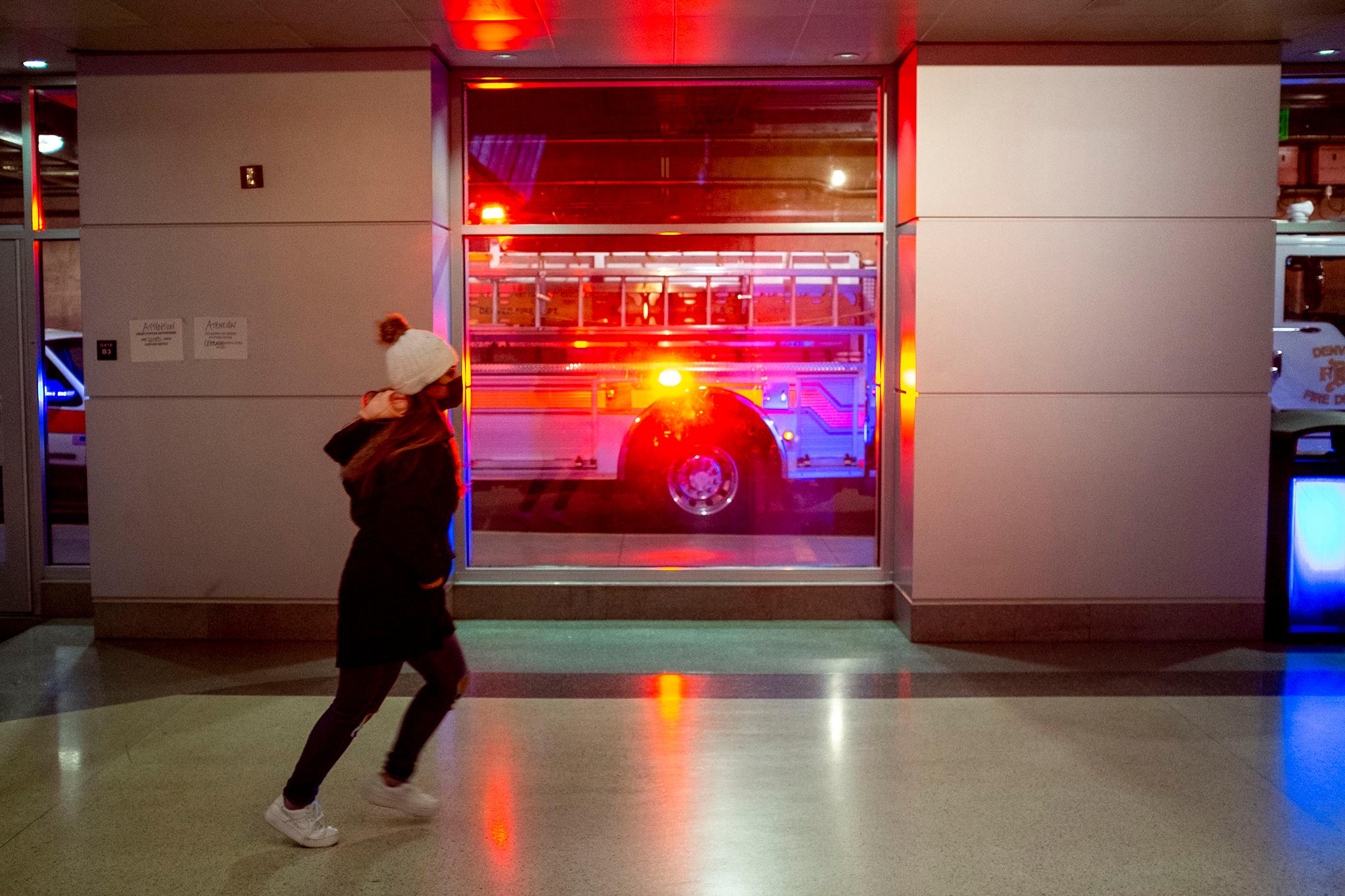

Meanwhile, city agencies and RTD, which manages the bus concourse and runs trains on the tracks outside the Great Hall, are ramping up their own efforts to address homelessness and crime. The transit agency has partnered with the Transportation Security Administration's VIPR teams, federal law enforcement tasked with ensuring the safety of transportation nationwide, to add security to the area and has recruited the red-clad civilian safely patrol unit the Guardian Angels. The agency also shut down the restrooms in the bus concourse for a remodeling, arguing the new design will add safety. New signs spell out what activities are not allowed, and benches outside have been torn down or fenced off to discourage people from lingering in the public space.

RTD also has increased its efforts to connect unhoused people and those dealing with addiction to resources. That's included hiring a full-time homeless outreach coordinator and four mental-health clinicians who work throughout the transit system.

Derek Woodbury, a spokesperson for the Department of Housing Stability, or HOST, said "the city is working with neighborhood groups to address issues surrounding drug use.

"In addition, it's important not to assume that all people who are experiencing homelessness have substance-use issues nor that all people selling and using drugs are necessarily experiencing homelessness," he said.

He points to the HOST Five-Year Strategic Plan, the city's plan to address homelessness by 2026, and the 2022 Action Plan, which outlines this year's work on the issue. The latter includes housing 1,400 individuals or families and expanding new housing options and outreach programs over the next year. The agency takes particular pride in what it describes as a Denver "housing surge": Over a 100-day period last year, the agency moved 576 people from homelessness into housing.

In a single day last year, 5,530 people were staying in shelters, according to the annual Point in Time Survey that documents how many people are homeless on any given night. That year, the number of people living unsheltered was not counted because of the pandemic. This year's count was completed last month and included unsheltered people, though the numbers won't be released for months.

"One of our key priorities for homelessness resolution is to better meet the diversity of resident needs for safe, temporary options," Woodbury said. "This includes investment of recovery funding into safe outdoor space, safe parking, tiny homes, and congregate and non-congregate shelter options. As our recent Housing Surge demonstrates, we also work to house people every day directly from both unsheltered and sheltered experiences of homelessness. The majority of people experiencing homelessness are sheltered, and more people are housed from sheltered situations than from unsheltered situations."

Solving the problem of addiction is not as simple as sending people to treatment programs -- especially when they don't have shelter, Woodbury explained.

"Many Denver residents, including both housed and unhoused individuals, are struggling with substance misuse," he said. "It is clear that recovery is more successful when housed or in residential programs that have duration needed and don't release back to unhoused situations."

Denver Public Health and Environment has also put resources into addressing drug use and homelessness in the Union Station neighborhood.

"There are many programs active within the city and available at Union Station to support residents who are experiencing mental/behavioral health or substance use issues, and/or who are experiencing homelessness," said Courtney Meihls, a spokesperson for the city's health agency. "We're committed to treating everyone with dignity and respect and to providing services compassionately and holistically."

The Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) program, which sends mental-health providers instead of police to certain 911 calls, provided resources to ten people in crisis in the Union Station neighborhood from early November 2021 to the last week of January 2022. In that same time period, the Early Intervention Team, which recently shifted to be under HOST, offered services to people in 20 tents in the Union Station neighborhood. The team offered Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program applications, support on court cases through the Denver Rescue Mission, case management referrals, and supplies to cover basic needs, explained Meihls.

Denver Public Health and Environment also has a Substance Use Navigator co-responder program that shows up with law enforcement and the Early Intervention Team to help people navigate substance-treatment options, though the agency could not account for how many interactions the SUN program had in the neighborhood.

"There's also Wellness Winnie, our mobile integrated behavioral health and support services vehicle that operates a consistent schedule throughout the city," Meihls said. "Winnie is staffed with mental-health counselors and peer navigators who offer peer support and navigation, behavioral health screenings and assessments, naloxone distribution and overdose education, and more. We are working to secure a second Wellness Winnie to expand these services this year."

The Denver Police Department is continuing to make arrests around Union Station.

From Nov. 1, 2021 to Feb. 1, 2022, Denver police documented 996 criminal offenses in the neighborhood, which had a far higher crime density, measured by crimes per square mile, than other neighborhoods in Denver for the first time last year. There were 478 offenses in the same time period a year before and 547 in the same time period the year The Coloradan opened. Most were low-level offenses, not violent.

"Officers have been directed to conduct patrols in that area to address the issues that have been brought to our attention through various sources," wrote Denver Police Department spokesperson Jay Casillas in an email to Denverite. "Officers assigned to this area employ several different strategies, to include saturation patrol, clandestine operations, providing services to people experiencing homelessness, and collaborating with community organizations and businesses to make Union Station safer.

"Denver police officers can make arrests for on-sight observation of criminal activity to include public drug use," he added. "With regard to individuals who are violating the city's illegal camping ordinance, our direction is to begin with providing notice of a violation and offering services, before advancing to citations and arrest."

The Hancock administration pledges to take swift but cautious action.

At the Feb. 2 press conference announcing the city's plan for addressing crime in 2022, he pledged to hire more police, sheriff deputies and social workers, to bring more cops to the Union Station neighborhood, and to continue to ramp up arrests.

"Our officers and the other agencies are doing their best to make it very clear that the type of activity that was going on down there before and during the holidays and even now will not continue," Hancock said. "We're going to bring every resource to bear to make sure we stamp it out."

While Union Station is not one of DPD's designated "hotspots" -- parts of the city with the highest amount of violent crimes and murders -- the Hancock administration plans to pay special attention to the area, the mayor said.

Union Station is "the welcoming center for the city of Denver," DPD Chief Paul Pazen said at the press conference. "Folks coming from the A Line and seeing our city, we need to make sure that those travelers feel safe, that our folks who utilize public transportation, that they feel safe. And we are helping individuals that may be battling substance abuse and mental-health challenges. So Union Station is an area of focus. It's not one of the violent hotspots."

There have been more than 522 arrests at Union Station in recent months, Hancock said. But Pazen added that arrests aren't enough. "Now, we have to ensure that we are continuing to offer support for folks as well," he said.

Raville, the director of the Harm Reduction Action Center, said that harsher penalties and more arrests aren't the answer.

"If stigma, shame and incarceration worked with drug use, we would have wrapped this issue up years ago," she said. "All that has done is drive use underground where folks have acquired HIV/viral hepatitis, and overdoses. We are wanting to do something different."

What the city hasn't tried at Union Station and beyond is a safe-use site.

"What we have seen that works in other countries such as overdose prevention sites (NYC just started their sites in early December and Rhode Island will start here in the next couple of months)," Raville said in an email. "It's happening in 11 countries and over 150 sites worldwide without an overdose death onsite."

Raville has been in touch with RTD leadership about the role the Harm Reduction Action Center might be able to play around Union Station and is eager to collaborate with residents of the neighborhood.

"HRAC has a robust street outreach team that engages in high drug traffic areas and encampments with resources/referrals, syringe clean up, syringe exchange, naloxone, fentanyl testing strips, along with garbage bags (it's hard to keep your encampment clean without bags), and water," she wrote.

Raville also encourages all Denverites to pick up syringes by the middle, put them in puncture-proof containers and throw them away. The risk, she noted, is low.

Raville is interested in collaborating with Safe, Clean and Compassionate on an overdose-prevention site and other harm-reduction efforts.

"We would love this group's support," Raville said.

But harm reduction strategies are a hard sell for some members of Safe, Clean and Compassionate.

"My intuition or emotional response to this is not to do things to make it easy for people not to use the resources that have been provided," Valin said. "Why are we trying to make that easy when we've got dedicated resources, you know, and teams of people to help manage and help those people?"

Instead, he and the others are gearing up to support and maybe even run themselves in local and statewide elections to push for more policing, more arrests and fewer encampments. Valin wants lawmakers to revoke a recent state law making possession of less than 4 grams of any drug a misdemeanor. The property owners are weighing who should take on CdeBaca in the next election.

"We represent the demographic that she cares nothing about," Mazzocchi said.

Because they are white, straight and successful, Valin said, CdeBaca does not respect the struggles of LoDo residents, nor does she offer them adequate representation.

"She's resentful of that," he continued. "Not that, 'Hey, they've earned it. They deserved it, because they make good choices and they contribute to the community.' And you know, that's my view of it. But see, the Candis don't see it that way. Anyone who's living at The Coloradan or Lower Downtown is undeserving, opportunistic, racist."

CdeBaca is aware of their political opposition and criticisms, yet continues to try to work with them, she said.

"I'm their kryptonite," she said. "I'm their boogeyman. But we try to do our due diligence and meet with them as frequently as possible. We literally dedicated a crime solutions meeting to them, and we let them call it that."

The property owners at The Coloradan and members of Safe, Clean and Compassionate are figuring out who they want to back in the next mayoral and gubernatorial elections. They're leaning toward Ganahl for governor and are looking for a mayoral candidate who wants to bolster DPD and undo criminal justice reform that has happened in the last few years.

As for what the members of Safe, Clean and Compassionate are trying to accomplish, Greenly said, they are pushing safety first.

"The movement goes back to: We lost our police during Black Lives Matter," Greenly said. "We lost our protection during COVID. Not just us in Denver. Our country did. And we are fighting to get them back. To me, that's the No. 1 priority."

But Greenly also offers resources to unhoused people, handing out hand warmers on her walks.

The property owners said their movement is growing, and politicians like CdeBaca, who have been outspoken critics of the Denver Police Department and the city's ban on encampments, will soon be out of office.

"We have a lot of brethren, if you will," Mazzocchi explained. "We have a lot of colleagues across the city. We're trying to make our thing not just about LoDo. I mean, that's our focus. This is the neighborhood we care about. We care about Union Station. But I can tell you right now, there's a lot of momentum and a lot of traction building across the city with these different activist groups to drive change."

CdeBaca sees the group as a viable political contender that could make Denver an even more hostile place for people with little money.

"I never underestimate them or the length they will go to get rid of people they don't like," she said. "They are often very privileged people who could navigate the law differently, who could amass the resources they needed to do real harm."

She worries that residents who are arming themselves will engage in violence in their quest for safety.

"With a vendetta like that, it sounds very similar to the Minutemen on the border, who were like regular citizens, average citizens who decided to police the border themselves," she said. "It's no different than that type of individual, like a vigilante, someone who wants to take the law into their own hands. Those are dangerous people. And I never underestimate them for the length they will go to get rid of people they don't like."

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated that Capitol Hill United Neighborhoods was the oldest RNO in the city. In fact, it was the Greater Park Hill Community, Inc. We also corrected timeline issues in Valin Thorn's story. We regret the errors. We also updated the story to clarify Greenly's and Thorn's perspectives.