In early March 2020, the first cases of COVID-19 were made official in Colorado. Nearly two years later, in February, public health officials suggested residents could breathe an unmasked sigh of relief and get back to business as usual in the weeks to come. For the second time since the coronavirus arrived, Gov. Jared Polis declared the emergency phase of the pandemic was over.

No more government mask mandates or vaccination requirements -- for now. City officials are headed back to work -- for now. Even schools have quit requiring children to cover their faces -- for now.

There were just 52 cases of COVID-19 reported statewide on Monday.

So what are Denverites thinking about Polis' declaration that the emergency is over?

To find out, we walked the city in early March, two years into the pandemic, and asked 10 people.

Here's what they said.

Graduate student and Colorful Colorado retail worker Joon Moon

In early March, Moon worked his last shift at Colorful Colorado, one of the oldest gift shops in Denver. He stood behind a plexiglass shield and wore a mask.

He was working alone on his final day, he said, because the two other people who should have been in the store were home sick with COVID-19.

Business as usual?

"What a joke," said Moon. "So out of touch. What a joke. No, this is just starting, man. I can't afford food. A lot of people can't. A lot of people are getting evicted right now, dude. Like, I could talk about the numbers and the science, but I'm just telling you what I'm seeing physically. I'm seeing people lose their homes. And it's going crazy... It makes me angry to think that some people think this is just ending."

Moon, a recent college graduate, is studying for his master's degree in water engineering. The education isn't doing him much good, he said, because he can't find a decent-paying job. So he's leaving Colorful Colorado to work at his own family's business.

"I know everyone's saying go into STEM and all that," he said. "It's not working out for literally anyone. It just sucks. So I'm really frustrated at all this."

He's looking for a place to rent, but he can't find anything he can afford. Older residents encourage him to buy, but the housing stock is so limited and expensive, doing so is unimaginable for someone in his early 20s.

As he looks for a new place, he's living with his parents.

"It's rent free," he said. "Sure, it's a little shamed upon, just because you are supposed to get a job right after college. But no one's getting a job. I know everyone out here is going, 'Oh, everyone's too lazy to work' and all that. But I'm on the other side of that. And I'm seeing these job apps, and they're insane. Five years, 10 years of experience for nothing minimum wage jobs."

The emergency phase is continuing, he said, because we haven't addressed the damage wrought by the pandemic.

"Denver itself has gotten way worse in the last year," he said. "This is a completely different city since we started the pandemic. It's so depressing. Everyone's always coming in here talking about how dangerous it feels out there."

Society, as he sees it, is collapsing.

"It's like the fall of Rome," he said. "There are so many problems, and we never went back to fix any of them. Whether it's the Denver mayor, the Colorado governor, the senators, or even just the normal people, none of us came back to fix the problem. So I mean, we're just reaping what we sow."

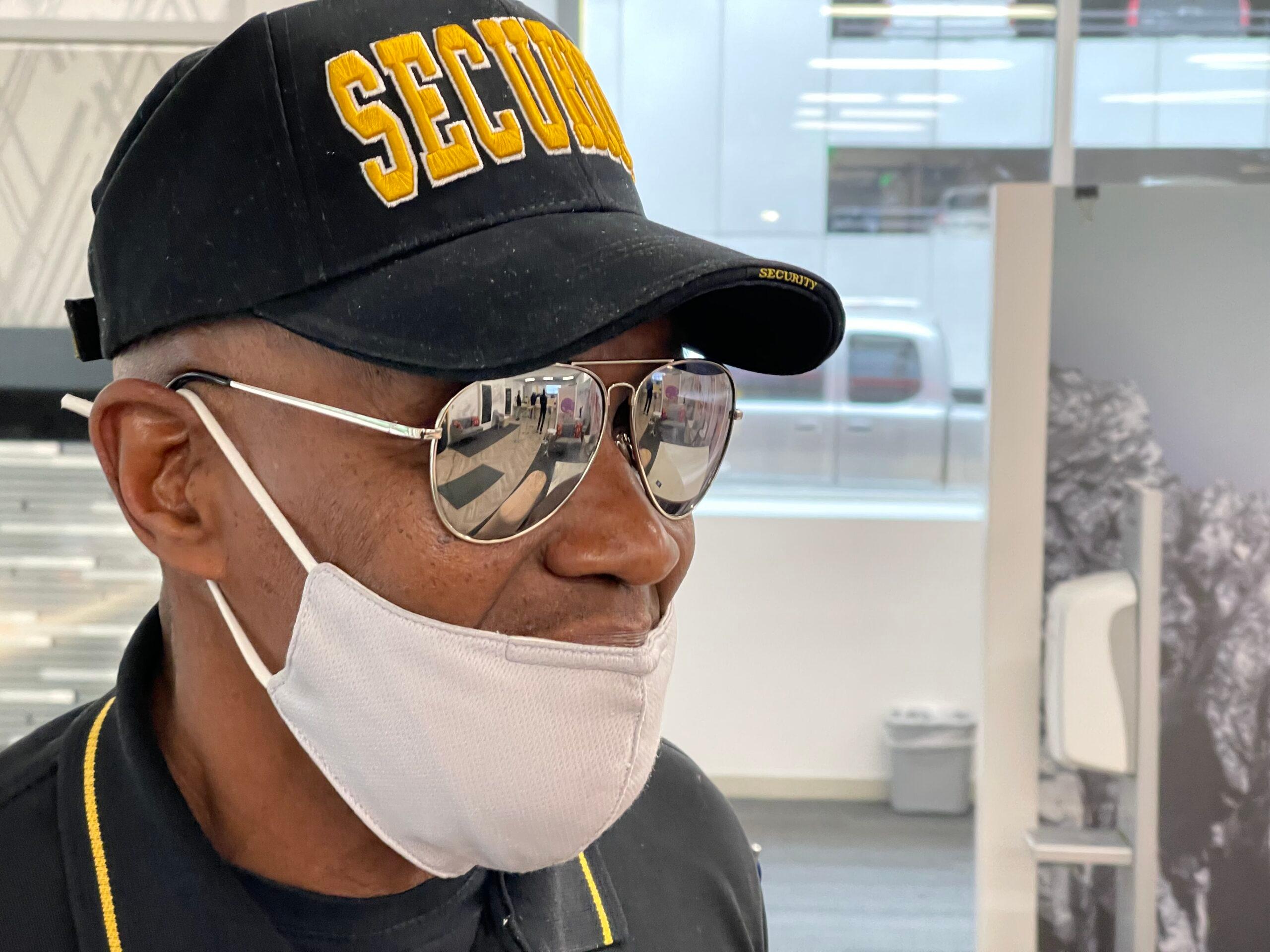

Army veteran and security guard Flozell "Sarge" Beasley

With a handgun on his hip, a hat that read SECURITY, and a mask, Flozell "Sarge" Beasley stood on the sidewalk in front of Wells Fargo, greeting passersby. He's on contract to guard the branch.

He said he's been careful during the pandemic, but not fearful.

"It's not been a big problem with me, because I'm an ex-military man," he said. "And I spent a lot of time in Africa during the Ebola situation. So it didn't frighten me."

He received all three vaccines, including his booster shot in July, and he's an evangelist to vaccine skeptics.

His argument, which has won him converts, goes like this: "You got people who say, 'Oh, the government is trying to eliminate us' and things of that nature. And I always tell people, 'The same people that okayed the shot, the FDA, is the same people that okayed your milk and your butter. So if they're gonna terminate you, why do you think they would just use a shot and not butter or milk or sugar...' If people say, 'Oh, I didn't think about that,' you know, I say, 'That's who the FDA is!'" And it works.

As for the notion that the emergency phase of COVID-19 is over, he's confident that for now it is, though he believes future outbreaks and variants could arise. If they do, the government should contain them -- even if it's inconvenient.

COVID has impacted Beasley's social life, though not terribly. He and his wife have limited the number of family and friends they invite to their Montbello home -- particularly when he's been unsure whether they were following public health measures.

Overall, he's been pleased with how his neighbors have responded to the pandemic.

"We got a lot of different nationalities and people in that neighborhood," he said. "But everybody is sort of going to do the things that they should be doing, you know, and being safe."

Retirees Francy and Peter McMahon

Wife and husband Francy and Peter McMahon, in their 80s, strolled from their condo through Uptown, past tents on the streets, enjoying a warm day.

Even as the virus has shifted how they live, they never felt burdened by regulations and enjoyed their lives.

"At this point, we don't scare very easily," Peter said.

A resident from their building was one of the first people in Colorado to die from COVID-19. Family members have had it. Along the way, the couple has followed public health orders.

"I come from a family of physicians," Peter said. "I'm a pretty strong believer in the power of medication."

They were in the first ranks to be vaccinated and have already received two boosters. Nonetheless, during the Omicron surge, Francy started coughing.

"I was supposed to go to the doctor that week," she said. "And I called him. He said, 'You're not coming in here. You've got to go have a test.' So we both went out, and I'm positive and [Peter's] negative, and he even had another test after that."

She was perplexed that she had COVID and he did not.

"I wasn't terribly sick," she said. "But I wouldn't recommend somebody get it. You're very tired. You don't want to eat, which is a good thing, because I lost a few pounds, but then I gained it back."

Though the vaccine did not prevent the virus, she's still grateful she received the shots.

"I guess it saved me from being very sick and not being in the hospital," she said. "Because I'm 85, and so, you know, I could have possibly gotten very, very sick. And I was. I mean, I could function, but we didn't need help or anything.

"Our grown children, they dropped off food and ran out the door," Francy added. "And I was fine. It was fine. But I feel sorry for the people who really get sick. And there's nobody around for them."

Through the pandemic, the couple kept their cool and never felt caught up in an emergency.

"We didn't panic," Francy said. "We didn't do any of that stuff. We just put our mask on. We washed our hands 100 times a day, you know, and used all that sanitizer. Would you like some? We've got gallons back in our condominium."

Though the McMahons find reasons to laugh, they are also quick to acknowledge the losses people have suffered.

"It's a terrifically serious, horrible event for so many people," Peter said. "I really don't like to joke around like we do, but that's how we get through everything."

Denver Public Library staff member Joshua Herrington

Joshua Herrington, who works at the Sam Gary Branch Library, unlocked his bike after a workout at the Carla Madison Recreation Center. He spent the past two years largely following public health orders, and for most of that time, he was COVID-free. Then came Omicron.

"I recently just got COVID for the first time after avoiding it for so long," he said. "And I honestly don't really know what is good or bad about opening back up fully and no masks and stuff. So it's hard to say how to feel about it. I really don't know how to feel."

Even as rules loosen, he's taking precautions.

"I usually wear a mask," he said. "I don't wear a mask at the gym, just because it's kind of hard. But pretty much everywhere else I go right now, I'm still wearing a mask."

The governor's declaration that we're out of the emergency phase is news to Herrington.

"I don't really know if it's a good idea or not to get out of the emergency phase," he said. "I didn't even realize we were in an emergency phase. So it's hard to keep up and hard to know what the science says."

Bryant of New York hairstylists Bryant and Rakiah Green

Bryant Green walked briskly up Colfax Avenue to the multicultural hair salon he runs with his wife, Rakiah Green, called Bryant of New York. The past two years have been tough at times, but their business has weathered the pandemic.

Not long after the first cases came to Colorado, the salon was shut down by the state for a month and a half, but reopened in May 2020.

Averse to borrowing money, he and his wife tapped into their savings to keep the salon running and are proud they do not owe the government money for Paycheck Protection Program loans.

After the initial shutdowns, Bryant said, it's been "business as usual," hardly a state of emergency. Mostly.

"It's slowed down business," Bryant said. "But pretty much, my clientele continued to patronize me. We had to wear the masks and everything. The only folks that I didn't see as often is the elderly folks, because they were afraid to come out."

Inside Bryant of New York, a younger stylist worked on Rakiah Green's hair as she recalled how the pandemic affected her.

"It was sad to see people coming in and feeling discombobulated," Rakiah said. "And this was their therapy. They just wanted to unload. And but for us, sometimes, it was overwhelming."

The couple would go home at night, exhausted from what clients shared.

"We heard stories," Rakiah said. "We heard about deaths, as well."

"And we lost a few clients," Bryant added. "Lost like not gonna be here anymore because of COVID."

As for being in a state of emergency, it hasn't really felt like that to the Greens since the lockdowns, when their business was closed. They don't see Polis's declaration as all that significant.

Despite public health officials recommending people get vaccinated, Rakiah opted not to. She has a mistrust of government health mandates and wanted to see more evidence that the vaccine was safe. Instead, she used herbs to boost her immune system.

"I didn't trust it," she said. "I said, s***, if it's my time, it's my time."

Rakiah recalled a client who is a runner who managed to keep exercising through the pandemic but quit taking care of her hair.

"She came in, and she had a dreadlock," recalled Rakiah. I asked, 'What happened?' She said, 'COVID happened.'"

The woman wanted Rakiah to cut the lock. "No, we won't cut it," she told the runner. "Let me try to get it out."

Rakiah left conditioner in the woman's hair for two days. When the client returned, Rakiah combed out what she could -- but some was still knotted.

"I just cut that piece out, gave her a good trim," Rakiah remembered. "I said, 'Let's let it grow out while we twist up everything else.'" The client agreed. Months passed. "Now her hair's all one level again."

Brown Palace employees Jenni Bowyer and Todd Zee

Outside the Brown Palace, Jenni Bowyer, a staff member at Ellyngton's, smoked on the sidewalk with Todd Zee, who supervises all the nineteenth-century hotel's kitchens.

The governor's idea that the emergency phase is over is baffling to the two restaurant workers, who have been laboring through most of the pandemic and haven't been too bothered by it at all.

"I worked the whole time," Bowyer said. "So I quit caring. It is what it is to me."

During a period of time when she was offered some unemployment during the pandemic, she was able to secure housing with the extra income.

"Honestly," she said, "it's affected me positively."

Wearing masks has not bothered either Bowyer or Zee, and they are hardly confident this pause in COVID restrictions will last.

"It's going to go back," Bowyer said. "I think so."

"It doesn't bother me either way," Zee said. "I'll wear it or not wear it. I don't care."

Business at the Brown Palace has been slower over the past two years, but that's turning around.

"We're picking up," he said. "We're getting groups in now. We've been pretty dead on the groups."

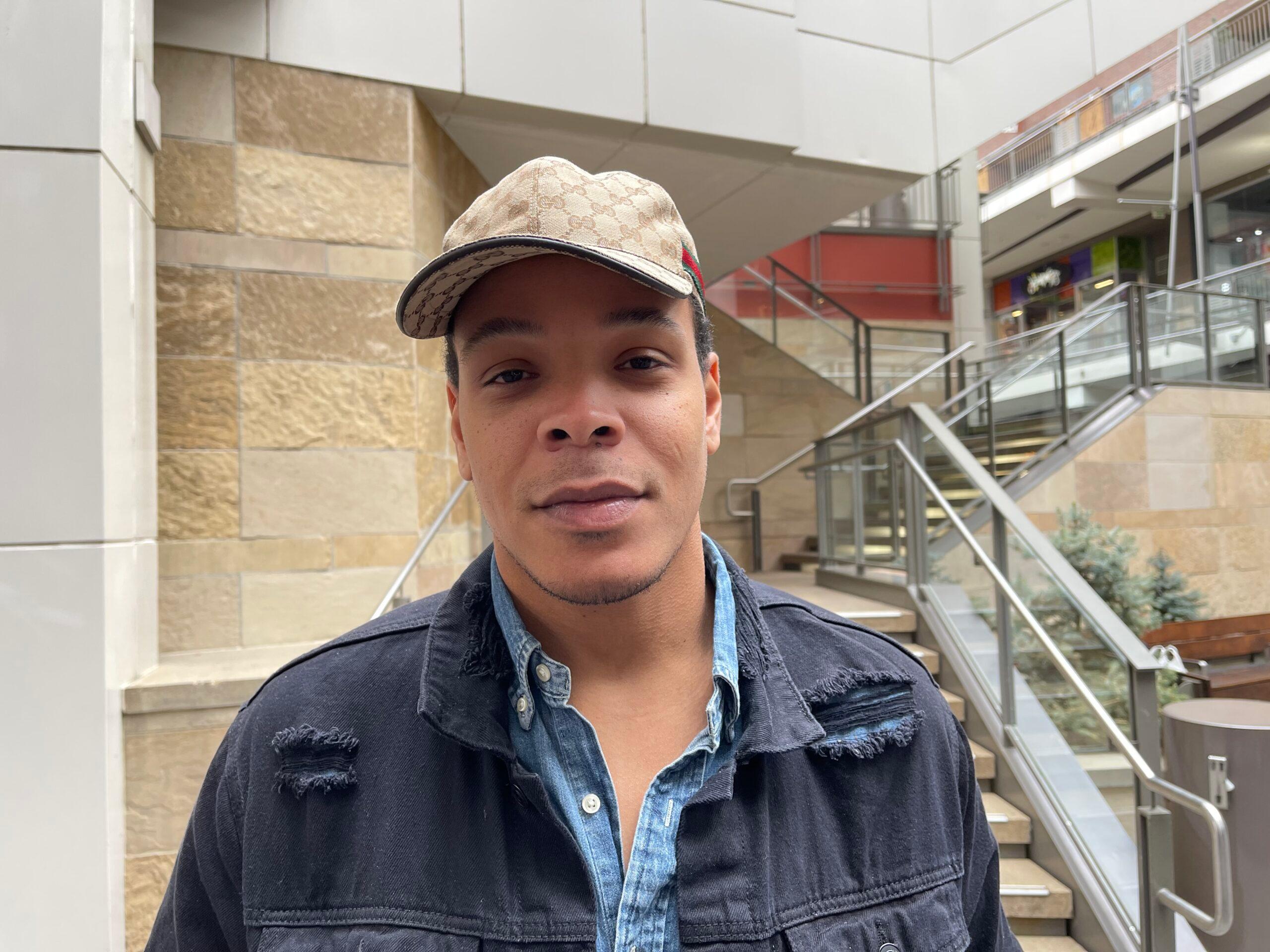

Larry Calcote

Larry Calcote and his mother are visiting Denver from New Orleans. They stood on the ground floor of the Denver Pavilions, outside Distortions Monster World, considering whether to go in and snap selfies in front of massive aliens, zombies and ghouls.

Calcote is a travel respiratory therapist who has spent six months working in Denver during the pandemic. He's been on the front lines of COVID-19 and has seen death up close.

"You're just clocking in every day and watching people that you've been taking care of for a month or so, and you show up the next day, and they're not there no more," he said. "It's tough. It isn't something I've ever seen before."

He's admired how other countries have handled the spread of the virus, and he wished the United States had done better.

"I feel like it's worse for us over here," he said. "And when I say us, I mean Americans. Because, you know, we got our free will, so people do what they want to do. And what they want to do sometimes slows up things. That's the beauty of it, but it keeps me employed. It's sad, man. It's sad."

So is COVID finally behind us?

"I don't really feel like it's going nowhere," he said. "I feel like we're just gonna have to live with it. It's a virus, so you know, you get one vaccination, and it mutates and another one comes around. So I feel like this is our future. It's about to become the norm. So we're gonna have to get tough."