Lydia is in second grade. She loves math and the performing arts. She's also one of the co-curators of the Clyfford Still Museum's latest exhibition, Clyfford Still, Art, and the Young Mind.

"I'm really excited," Lydia said. "That's how I'm feeling right now. Like, where are you going?"

Lydia and her classmates got to look at pictures of the Abstract artist's work over video chat and choose objects that would be displayed in the museum, as well as how they'd be laid out. They also got to participate in exercises to further engage them in Still's work. Lydia remembers one day in particular, when the museum staff drew the outline of Still's "Big Blue" painting on the ground and invited the class to lie down in it to see if they were as big as the painting. Lydia said "Big Blue" looked like the ocean: It was so big that it was impossible to cover.

Lydia is also one of a few students who got to record a voiceover for the museum's audio component, which guides visitors through the tour and helps interpret Still's works. After each recording, her teacher Karl Horeis gave her a skittle (her favorite flavor is orange). Her voice greets you when you enter the museum.

"Welcome to Clyff Still Art and the Young Minds! The exhibit was created with children like me," she says. "My name is Lydia, and I'm six years old."

Horeis said he was impressed with the Clyfford Still Museum team for valuing young people.

"They are our future, after all," Horeis said. "Teachers obviously believe that, too, and it was neat to see someone else in a fancy museum downtown really prioritize children and value their voices."

The museum staff worked with more than 250 co-curators who ranged in age from six months to eight years old on every step of the exhibit's curatorial process, from art selection to marketing.

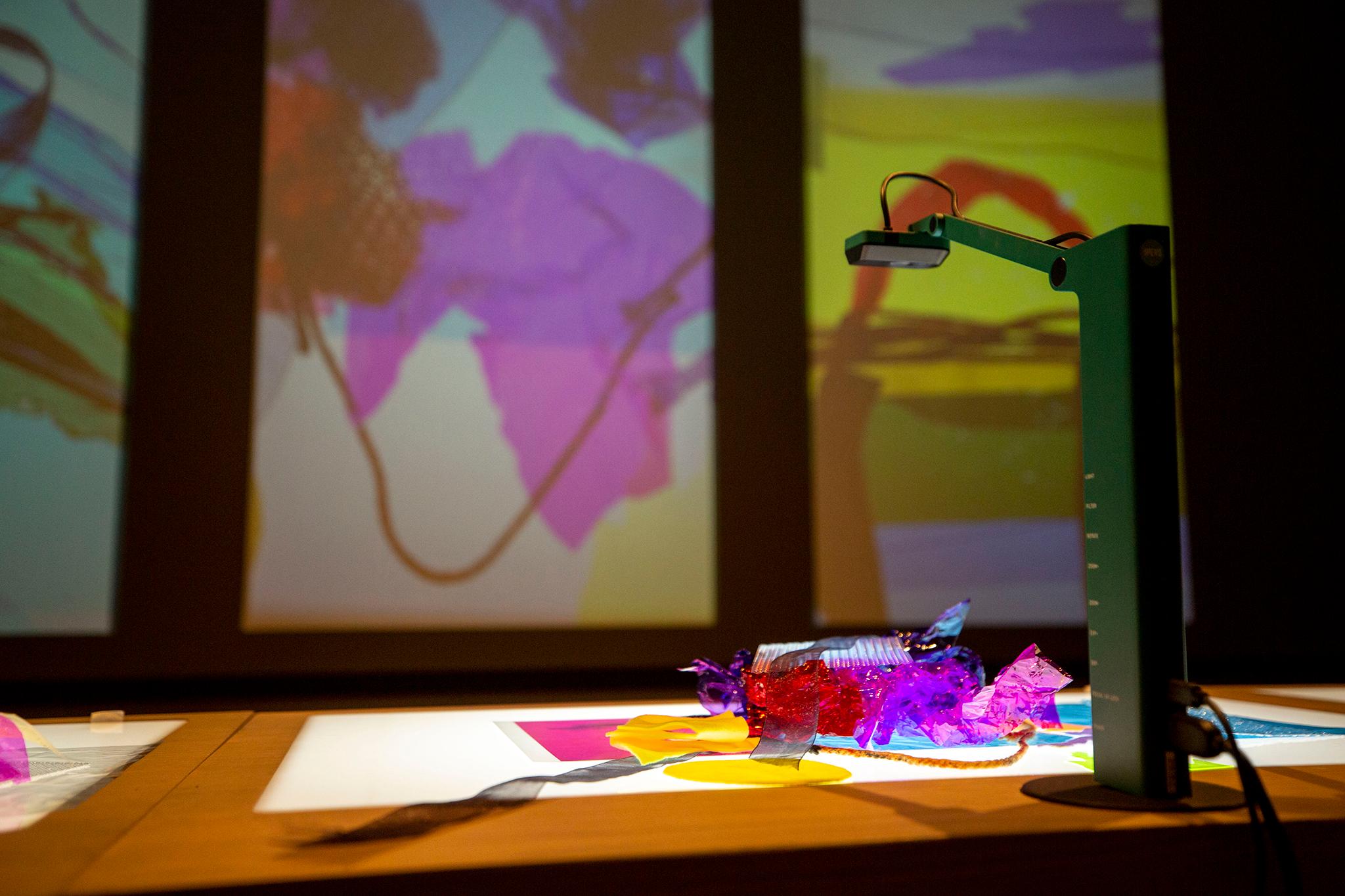

While the first four galleries in the museum are still arranged in chronological order to reflect the narrative of Still's life and artistic path, the remaining galleries were curated by children across the Front Range. They were arranged into five themes that reflect research on child development and what makes children engage with art: high contrast, scale, pattern, their surroundings and color. The young curators also helped to design interactive activities and provided their feedback about the works, which is shared in audio, video and written content throughout the exhibition in English, Spanish and American Sign Language.

"We started to think about what it means to work with children in a meaningful way," said Nicole Cromartie, the museum's director of education and programs. "People think curating is just picking the objects, which, of course, is a huge part of the process. We didn't want it to be just about that. We wanted to really form relationships with them. We wanted them to understand what it means to make an exhibition, sort of the big picture."

The young co-curators helped to design the gallery spaces, interpret the works and determine how the art would be displayed, and also assisted with elements like programming and social media campaigns. A few different groups designed some interactive activities. Bailey H. Placzek, associate curator and catalogue raisonné research and project manager, said it has been a complete rethinking of the Clyfford Still Museum.

"We're just really excited about these new voices and, like, this new feeling that has kind of permeated every room in this museum," Placzek said.

To recruit their young co-curators, the museum partnered with eight different schools, as well as childcare centers and Colorado State University's Early Childhood Center. Initially, they worked with the co-curators over Zoom. As the pandemic shifted in Denver, they began to work with the youth outside and occasionally in the museum with masks.

The paintings in one gallery were selected entirely by preverbal infants. The museum had parents or caretakers show the babies two color reproductions of Still's pieces at a time. The co-curators would "choose" a piece when they showed a strong response to one. Often, their eyes would light up, or they'd point or vocalize, or simply stare fixedly at one of the pieces. The exhibition features multimedia elements, including a video showing the infants selecting the pieces.

"It feels like a cohesive gallery for sure," Cromartie said. "I was just with an installation person who didn't know that the gallery was curated by infants. And it came up and he was just so shocked, like, 'Babies picked all of these paintings?'"

The museum started to work on the exhibition about three years ago, after brainstorming ways to connect with more audiences.

"In particular, families with young children are just generally such an exciting audience to work with," Cromartie said

At first consideration, it might seem that Still's abstract expressionist work might not resonate with children. But Cromartie said it was a natural fit.

"There is this misconception that abstraction is too esoteric for young children, and that just couldn't be further from the truth," Cromartie said.

Young children tend to have preferences for bright colors and high contrast -- key characteristics of Still's work. Placzek noted that the first works of art we create as babies and toddlers are abstract.

"I think that watching them identify these shapes and lines that they relate to and that they feel that they themselves can create helps create a connection right off the bat," Placzek said.

Placzek said that seeing Still's artwork through the eyes of children led her to understand it in a new way.

"I started to wonder if this is why his work has such power across the board, in terms of, no matter the age, no matter your background," Placzek said. "Because these themes are relevant to our fundamental visual development. Like, how we see the world from six months old."

Comartie said she hopes young visitors will feel inspired when they see that other kids created the exhibit.

"I can't wait to see young children come in the space and say, 'Hey, I could do that, too!' And feel like this is a space for them," she said.

Placzek and Comartie believe that engagement in the arts can contribute to a young person's visual literacy, language development and social emotional development. It can teach young people how to talk about difficult topics through the lens of a work of art. Placzek said it can also help them feel affirmed in their imagination and their interpretation of the word. For example, children might look at one of Still's pieces and see a megalodon. They might look at a pastel and see a tunnel for "a hungry, scary monster."

"All of these are right, and there's no right answer,"Placzek said. "So I'm excited to kind of see people's eyes light up in the galleries when they recognize that."

That's a realization Placzek said can benefit adult visitors as well. The idea behind the exhibition is to make the gallery space more accessible to everyone. Working with kids to curate and interpret Still's work reinforces the notion that you don't need an art degree to appreciate abstract art.

"We're hoping that by our adult visitors seeing these children's voices and interpretations on the gallery walls, and elevated, validated, that that helps them feel more comfortable feeling validated in their own interpretations of the works and feeling like their own personal interpretations are right," Placzek. "We want people to kind of question their own understanding of what it means to be an art expert."

Lydia is "excited and really proud" that people visiting the museum will get to hear her thoughts and opinions about the art.

She says she likes abstract art.

"It looks nice," she said. "I heard that you can see whatever you want in it. I saw one of the abstract art, and it had blue lines and yellow background. And I'm like, it looks like a yellow storm."

She said that while math is her favorite subject, she is interested in art. She likes building with blocks, and her brother is teaching her how to build with Legos.

We asked her what she thought about getting to see how a museum works.

"It makes me sound like I want to go home and do my own creation," she said.