Baby Rowelin had a sour look on his face as Father Stephen Osburn dunked him for a third time into a basin of holy water on a recent Sunday. His godparents beamed as the newest member of a long line of ranchers and farmers was baptized in the religion their ancestors brought with them from eastern Europe.

St. Mary's Holy Dormition Orthodox Church is in Calhan, between Denver and Colorado Springs. Its nearly-century-old chapel, with sky-blue steeples, rises above rolling hills that stretch as far as the eye can see. The building is the second house of worship constructed in these fields by a small community of immigrants who moved to Colorado around the turn of the 20th century. Many came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which stretched from modern-day Croatia to Ukraine.

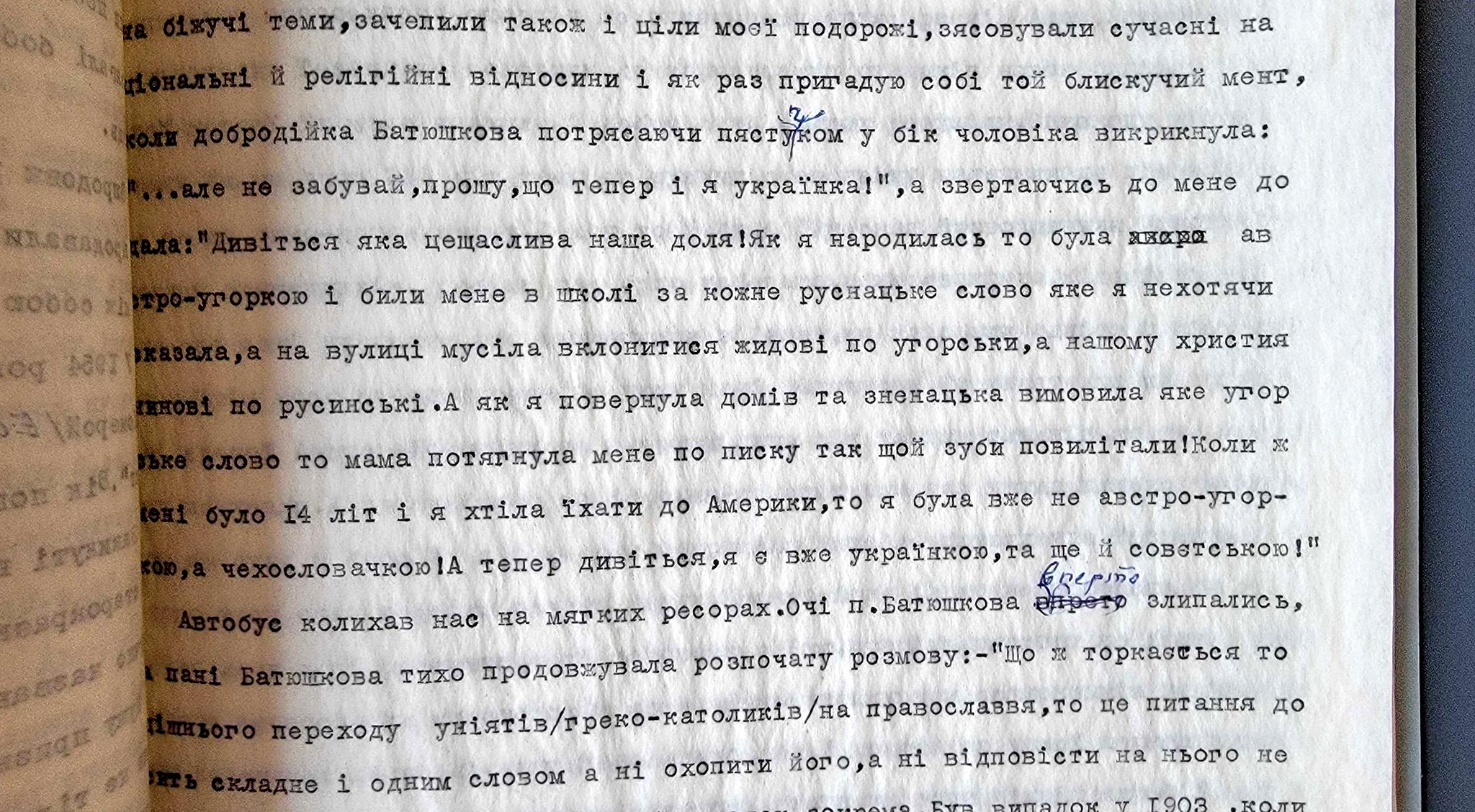

We decided to give St. Mary's a visit after Denver Public Library librarian Alex Hernandez told us he was digging into immigration from Ukraine to Colorado. His research unveiled a history, written in Ukrainian, that called this piece of the plains "Little Carpathia."

Here's what Hernandez found.

He told us he's been thinking of telling stories about immigrants for a while. His dad was a "child refugee" from Cuba, and he had a sense growing up that his paternal cousins felt removed from what it meant to be an "American." The series he envisioned was meant to show first- and second-generation Americans that they belong, and that they're linked to so many others with similar experiences.

"I want those kids, even if they might be born here, to have more agency - to recognize that people from all over the world have been coming here for a long time," he said.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, Hernandez realized the time for his project had arrived. He'd begin by writing about Ukrainian immigrants.

Hernandez begins his blog post with a note on how complicated it is to nail this history down. The borders of present-day Ukraine shifted a number of times through the last 200 years - and could again soon - which means tracking nationality in the early 1900s is tricky. Some people we met at St. Mary's, for instance, identified as Slavic Czechs.

Still, lineages from the region are interconnected. Slavic people were part of a melting pot of settlers that founded the city that is known today as Kyiv (NPR's history podcast, Throughline, has a great episode on Ukraine if you want to hear more abut this).

In his research, Hernandez learned that people from present-day Ukraine came to Colorado for the same reasons a lot of immigrants did: to find steady work and a better life. The end of World War II and the foundation of the Soviet Union accelerated this influx, he wrote.

Some ended up in Pueblo to help manufacture steel. Others landed in Denver's Globeville neighborhood, where they also worked in metal smelting. There's an old-fashioned, standing-room-only Orthodox church in Globeville that's still in use; Hernandez wrote that Slavs first worshipped there before they founded their own congregation, in Sunnyside. The war in Ukraine has become a central topic of discussion at that church.

Hernandez also found that some who arrived in Globeville and Pueblo relocated to the eastern plains, especially after the 1862 Homestead Act made it possible for people to stake out their own land in Colorado. A deep dive into the place they settled, written in 1962 by immigrant and DPL librarian Lev Bykovsky, called the area north of Calhan Little Carpathia. It was even advertised to other immigrants in brochures left on tables inside the Globeville church.

"Quite natural it was that they settled for the most part on the land, which was within the boundaries of their known abilities and ties, not far from the centers of their previous work," Bykovsky's history reads.

When the text was published in 1962, its authors estimated that "60 families of 'Rusyny' (Ukrainians)" had settled in the area, totaling as many as 400 people.

(There are some great photos from Little Carpathia in the 1950s that are part of the Denver Post's photo archive. We can't place them in the story for copyright reasons, but you should click here to see them.)

Wherever they established homes, Ukrainian immigrants and their children were impactful for the state, Hernandez wrote. In 1965, for instance, then Gov. John Love "declared official recognition" of Ukraine's unification as an independent state in 1919 (though that autonomy was dashed by Russian and Polish invasions before World War I).

Here's what we found on our visit.

The descendants of the 60 families detailed in Bykovsky's history still remain on the land today. But Little Carpathia, the old-timers told us, was likely a name given to residents of Calhan by people outside of their community.

John "Butch" Sakala, who grew up in the area, remembered neighbors who used coarser ethnic slangs to describe his community.

"We was the bohunks north of the tracks," he said, "bohunk" being the derogatory term of the day to describe eastern European immigrants.

Georgianna Glover, whose grandparents immigrated here around 1900, grew up speaking Slovak and did not learn English until she went to school. She also remembered high tensions between the families of Little Carpathia and other settlers further south.

"At the turn of the century, it was bad," she told us. "We had a different religion, and they were more Catholics and Lutherans, and here we were. And church was in Slovak."

While life here hasn't changed a whole lot since she was a girl, Glover said relations with the neighbors did become a non-issue over time.

"The people south of Calhan realized that we're just like they are," she said.

In church, after baby Rowelin's baptism, Fr. Osburn led his congregation through liturgy.

Services here are in English now, but nearly everyone in the pews can trace their roots back to those early settlers.

Glover, whose father helped build the church, said the community's founders were so poor they had to use old tables to construct pieces of the ornate walls inside. Darlene Mikita, who grew up nearby and was surrounded by a flock of grandchildren, said 80% of today's congregation is likely related in some way, though most who grew up here married outside the church.

In his sermon, Osburn quizzed kids sitting on the floor around him on why religious icons - paintings of saints and holy figures - cover the church's walls. One answer: These frames are windows into heaven. But he said it's also a reminder of what a church is.

"It's a community. That's what this place is," he told the children. "What seems like chaos, really to [God], is not enough."

And as he said prayers, Osburn asked God to protect the people of Ukraine and quell the violence in the region.

"We pray for all nations," he told us later, though Ukraine is also an Orthodox country that's tied to his congregation in a particular way.

Both Glover and Sakala said they feel that connection to the people of Ukraine. News of Russia's war, they said, is felt in a unique way here.

"It's a sad deal, and we pray for them all the time," Sakala said. "It hits us pretty hard."

Correction: The photo captions in this story originally stated St. Mary's is located in Simla, Colo., and have been corrected.