Shaniq Wells considered quitting her long career as an early-childhood educator during the first year of the pandemic.

The childcare industry saw a mass departure of teachers who have gone on to work as nannies or in other fields altogether. Statewide, 60% of childcare centers struggled to keep staffed during the pandemic, according to the Bell Policy Center. Many centers closed for good, leaving parents scrambling for someone to keep their children alive while they worked to pay the bills.

The pandemic and low pay played roles in teachers leaving, but for Wells, there was more. Despite two decades in the field, she felt undervalued -- not by families and children but by the principal at the school where she was teaching. Early-childhood educators lacked the respect and pay society afforded other professionals, racism sullied the field, and she was watching her fellow Black teachers leave childcare as the cost of living rose and wages didn't keep pace.

"Being a Black educator, out here, there's not too many of us in the education field anymore because of the pay," she said. "We don't make enough as teachers, as educators. They want us to take all these trainings and jump all these hoops, and we still don't get paid more."

In the early days of the pandemic, schools shut down, and Wells' hourly pay quit coming in. She decided to leave the classroom to be a nanny but that proved challenging.

In the classroom, Wells set the rules. Inside someone else's home, the parents did.

"When you're in your own classroom, it's your rules versus teaching in the home of the child," she said.

Parents who were working from home during the pandemic were constantly watching and intervening in Wells' interactions with their children, which disrupted Wells' flow. She felt like she was overstepping their boundaries and that it was hard to set boundaries of her own.

Nannying also gave her an insight into some of the behavioral issues she had seen in children. She saw parents struggling to manage their kids' behaviors at home, and many of these adults also had trouble coping themselves.

She considered leaving childcare altogether, but the classroom called her and she answered.

"I'm passionate about what I do," she said. "You know, I genuinely love kids."

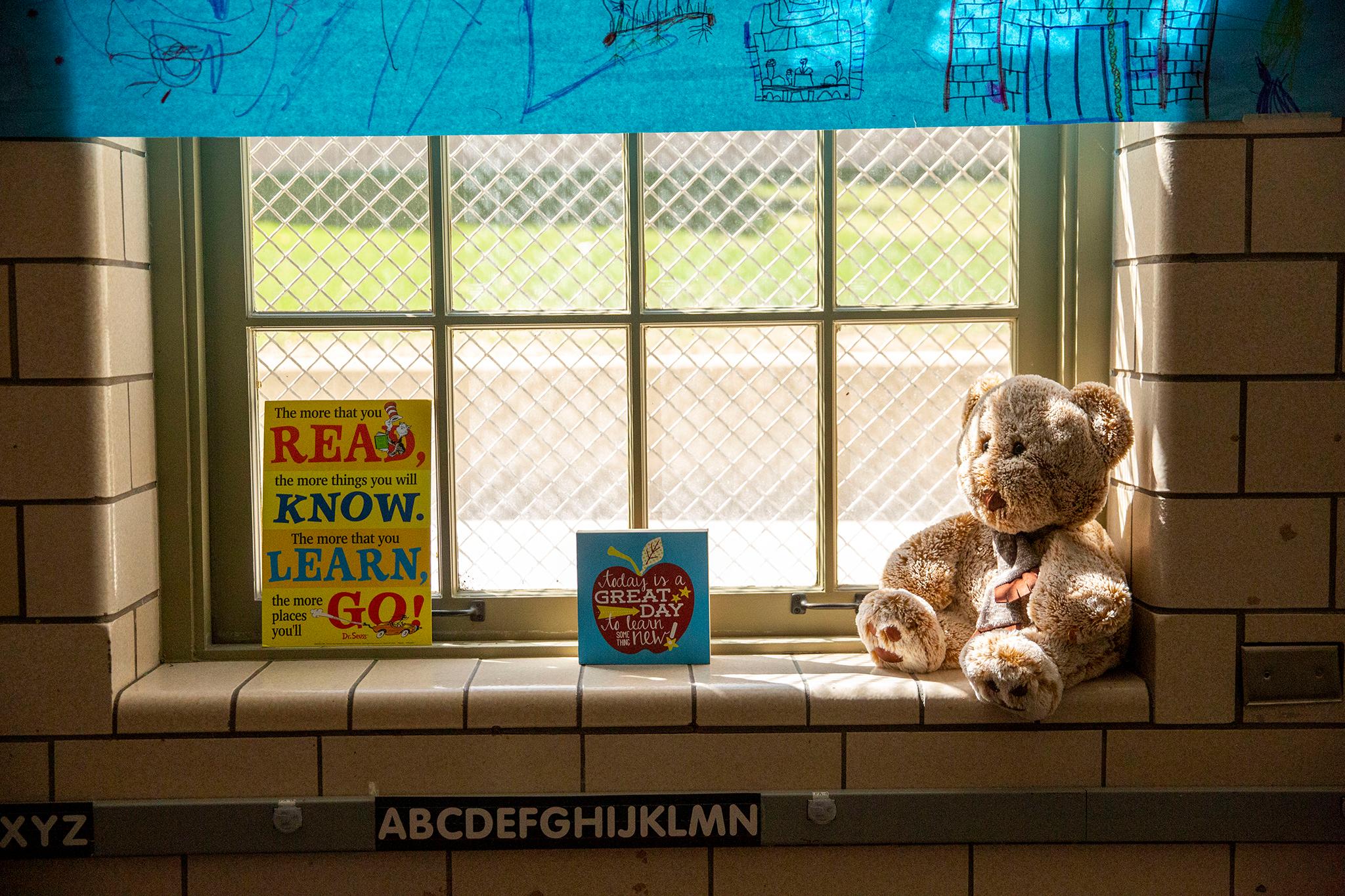

She took a new job at Trevista at Horace Mann in Sunnyside. She loves the new program, though it pays less than she was making as a nanny and her early mornings and afternoons are split by school days.

Despite her two decades in the field, Wells makes $22 an hour as a contract worker running the school's before- and after-care programs. Working full time, that amounts to $45,760 a year. Her salary is less than 50% of the area median income for a family of three. While that makes for a tight monthly budget, she makes too much to qualify for many forms of public support.

To pay for her downtown rent, car payment, student loans and high-school aged daughter, she has had to work multiple gigs on top of long days in the classroom -- sometimes as many as five jobs. On top of teaching, she moonlights as a face painter, an artist, a photographer and a party planner.

"My friends call me a Jamaican because I have a lot of jobs," she said.

These haven't been the greatest struggles in her 20 year career. Being an early-childhood educator and a mother was particularly daunting.

"When I got pregnant with my son, I had to work all the way up to my due date," she said. "And I think I took three weeks off, but it might have been two. But I was right back at work ... because it's like, how do I pay my bills as a single parent?"

When her son, who is now 21, was six, she would leave work to pick him up, drop him off at their home, and leave him alone for a couple of hours. She had grown up the same way, getting herself ready for school and taking care of herself when she came home, while her parents worked long hours. She taught him how to make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and told him to stay away from the stove.

"I was like, hey, if I did it, he can do it," she said.

Though he's grown into a stable adult, the situation never felt fair.

Wells acknowledged single parents' struggles are even harder now.

"I can only imagine now what folks are going through, because things are way more expensive," said Wells. Especially childcare.

She is watching her own colleague's struggles being an educator with a newborn.

"My coworker just had a baby a month ago," Wells said. "I don't even think the baby is a month yet. She has a baby. Because she can't afford to miss work, she literally came back to work a week later. It was a struggle for her. ... She had to do it because she couldn't afford to not be at work. A week later? Your body hasn't even healed. It takes six weeks for you to heal. You know, you can't even take six weeks off to bond with your baby to be with your family... When we talked, she was like, 'I can't afford to miss work for six weeks. I can't pay my bills.'"

Wells recalled recently holding another parent who was in tears over the struggles of raising a four year old. The kid was having behavior issues, and the mother was overwhelmed in deciding whether to give the child psychiatric medicines as a doctor had suggested. Wells offered her expertise and consolation.

For Wells, being able to provide love, guidance and wisdom to parents is as important as taking care of the kids.

"I'm here to support you and your kids. Not just your kids. I'm here to support you, too," she said. "How can I make our days better? Not just my day. I don't want to be selfish. I shouldn't be like, 'Look, I got to deal with your kids all day.' You know, I don't want to be selfish like that. How can we make the world better for ourselves?"

And it's that question that continues to keep her in the field.

"That's why I don't want to give up," she said. "I don't want to be discouraged. You know, when I walk into the school, I want to be welcomed, you know. I want to be successful. I don't want these kids to go out into the world and be lost and not given a chance."

Over the next few weeks, Denverite will be exploring the state of childcare in Denver. Do you have stories you want to share? If so, write me at [email protected].

Explore the series:

Multi-year waitlists, tuition as expensive as a second mortgage: Denver is in a childcare crisis

Denver's broken childcare system forced this single mom to declare bankruptcy

Here's what being 'super, super, super lucky' looks like in Denver's childcare crisis