The night a driver struck Javin Odegard, the 32-year-old metalhead had joined coworkers at a bar to watch the Avalanche ultimately lose the fifth game of the Stanley Cup Finals. He had just finished his shift at Patagonia.

The friends joked around. They mourned their home team's loss. They said see you tomorrow.

Tucking his long black hair into his Avalanche hat that Friday night in late June, Odegard mounted his bike and pedaled home to meet his 72-year-old father.

Around 11 p.m., his dad, Sid Odegard, waited. Javin -- who also worked as a bike courier and played the market to make extra cash -- gave generously to the people he loved. Especially his father. Javin paid the bills and made sure they had food.

He said he'd be home early, so where was he? He often ran late, but not this late.

His older sister, Lavita Garcia, 34, was working her second job for a catering company that night. She had served tacos at a bar and had leftover meat, so she called Javin to see if he and Sid wanted the extras. The call went to voice mail. She rang up her dad, who wanted the food.

Lavita dropped the leftovers off around midnight. When she showed up, Sid wondered why Javin still wasn't home. Lavita and her dad guessed he was out with his girlfriend.

On Saturday morning, staff at Denver Health -- the same hospital where Javin was born -- called and told the family to come. Now.

"As soon as we got to the hospital, it was very weird," Garcia said. "When you go into a hospital, you expect long wait times."

The family had experience with hospitals. In 2016, Javin had been riding his bike near 12th Avenue and Knox Court when he was hit by a driver of a large, black SUV. The driver fled. The crash broke Javin's arm. He was taken to Denver Health, where he spoke to media, demanding justice.

The family's hospital visit in June was different. When the family arrived at the ICU, a staff member was waiting for them at the nurse's station. She said there was a man there with a brain injury. He had been picked up Friday night, a few blocks away, at 6th Avenue and Fox Street. The nurse believed he had been hit by a car, and she asked the family to identify him.

"We walked in the room," Garcia said. "Of course, it was my brother."

The stem that connected Javin's brain to his spinal cord had been damaged, she said. His brain had swollen, and the doctors had removed part of his skull, trying to save him. He breathed through a ventilator. Despite life support, he was unlikely to survive, staff said, telling the family to call the people who loved him so they could say goodbye.

Garcia took charge. She called Javin's boss at Patagonia, who shut down the store for the weekend so staff could go to Denver Health. Word spread, and within an hour, more than a hundred people from the store, his bike courier community and the metal scene had arrived in the waiting room. They stayed at the hospital until late Saturday night.

When Garcia returned on Sunday, she watched the doctors perform tests.

"If he were not to pass any of them, that's when they could pronounce the time of death," she said. "So they did a few things. I was in the room. He didn't pass any of the tests. So they said he was braindead at 12:14 p.m. on Sunday, the 26th of June.

"People continued to come by and say hi," Garcia continued. "And I think it was around 7 p.m. when we finally decided to pull the ventilator off."

Five minutes later, he flatlined.

"After he finally passed, we asked the nurses to turn on the TV so we could watch the Avalanche game," Garcia said. "That was the last game. My dad, myself, my daughter, my boyfriend, my son, and my brother's girlfriend, we all laid there with him, and we watched the Avalanche win."

Denver erupted in celebration. So did Garcia and her family.

"We were in the room screaming," she said. "We were the loudest people in the ICU."

Since 2011, 31 bicyclists have died on Denver's streets. In 2017, Mayor Michael Hancock announced his plan to end all traffic deaths by 2030.

The program is called Vision Zero and is based on a Swedish plan from the late '90s that cut traffic fatalities by nearly half.

But so far, drivers continue to kill, at least in Denver. Traffic deaths have risen, and in 2021, the city saw more fatalities, 84 in total, than it had in any of the previous twelve years.

Already, at least 45 people have died on Denver's streets in 2022, according to city records. Of the 44 fatalities Denver police have documented, fourteen involved a pedestrian, and one involved a scooter. Most were motorists. Javin was the sole biker.

Sixteen of the 2022 traffic fatalities have led to charges: felony hit and run, careless driving with death, or vehicular homicide. In 22 cases, there were either no charges or charges hadn't been filed. Six cases, including the one against the man who hit Javin, are pending investigation.

As the investigation continues, the weeks since Javin died have been "like hell," Garcia said.

Her father worries about surviving without his son. Garcia promised to help her dad stay afloat, but with three children of her own, she's not entirely sure how.

Her family didn't have money to pay the funeral home and cemetery, so one of Javin's coworkers set up a GoFundMe and gave Garcia access to the account. She lost her log-in information, and when it came time to settle the bill, she didn't have access to the money. The funeral home threatened to cancel the service but ultimately worked out a deal. The cemetery has refused to bury him until it receives payment.

The day before Javin's July 15 memorial, Garcia's boss fired her. Between grieving and preparing for the funeral, she had taken too much time off of work, her manager said.

The investigation, which Denver Police Department confirmed is ongoing, has dragged. Javin's family has struggled to get updates. From what they've been told, the driver was sober. He stayed on the scene.

"What I've heard is that they're going to probably dismiss everything on him," Garcia said.

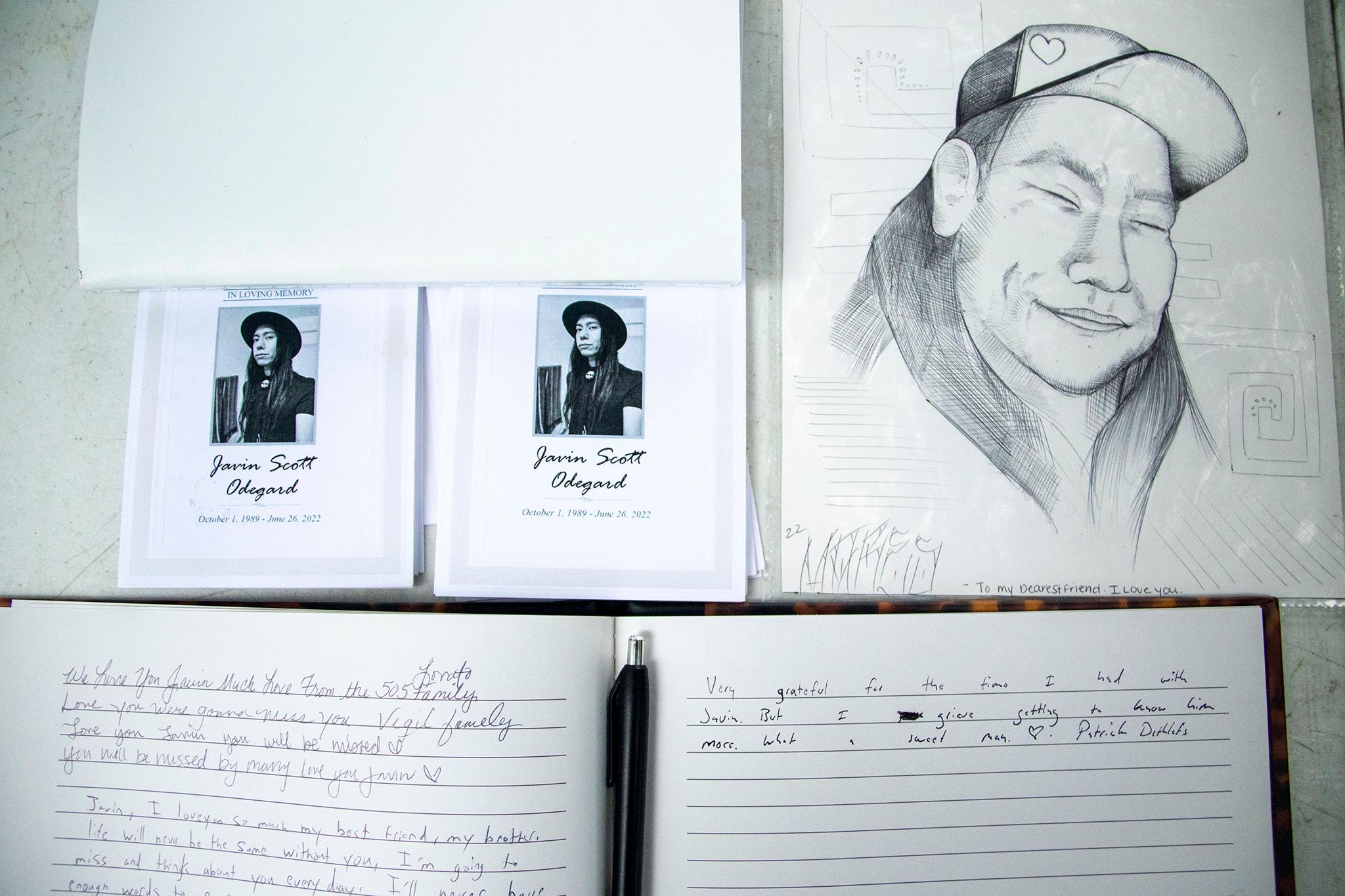

On July 15, the night of the memorial service, friends, coworkers and family gathered in Cheesman Park to remember Javin under a cluster of trees where he'd celebrate his birthday.

"Every year, he would buy a piñata for his birthday," recalled Garcia. "Like a unicorn piñata or like Baby Yoda ... different types of piñatas. And him and his friends would break it every year. So we bought a huge unicorn piñata."

Javin picked the cluster of trees in the park for his birthday because it was accessible to bikers.

The night of his memorial, dozens of people showed up -- some from his past job as a bike courier for Jimmy John's, others from the Confluence Courier Collective. His Patagonia co-workers were there. And so was his family.

Many wore black shirts, designed by a friend, that depicted him sitting between skulls and bike wheels, encircled by the phrase "SHARE THE ROAD."

When Javin celebrated his birthday, he didn't receive presents. He gave them.

There were concert tickets to Slayer and Megadeth; flights across the country; trips to metal festivals in New York, California and Europe; and even commissioned art.

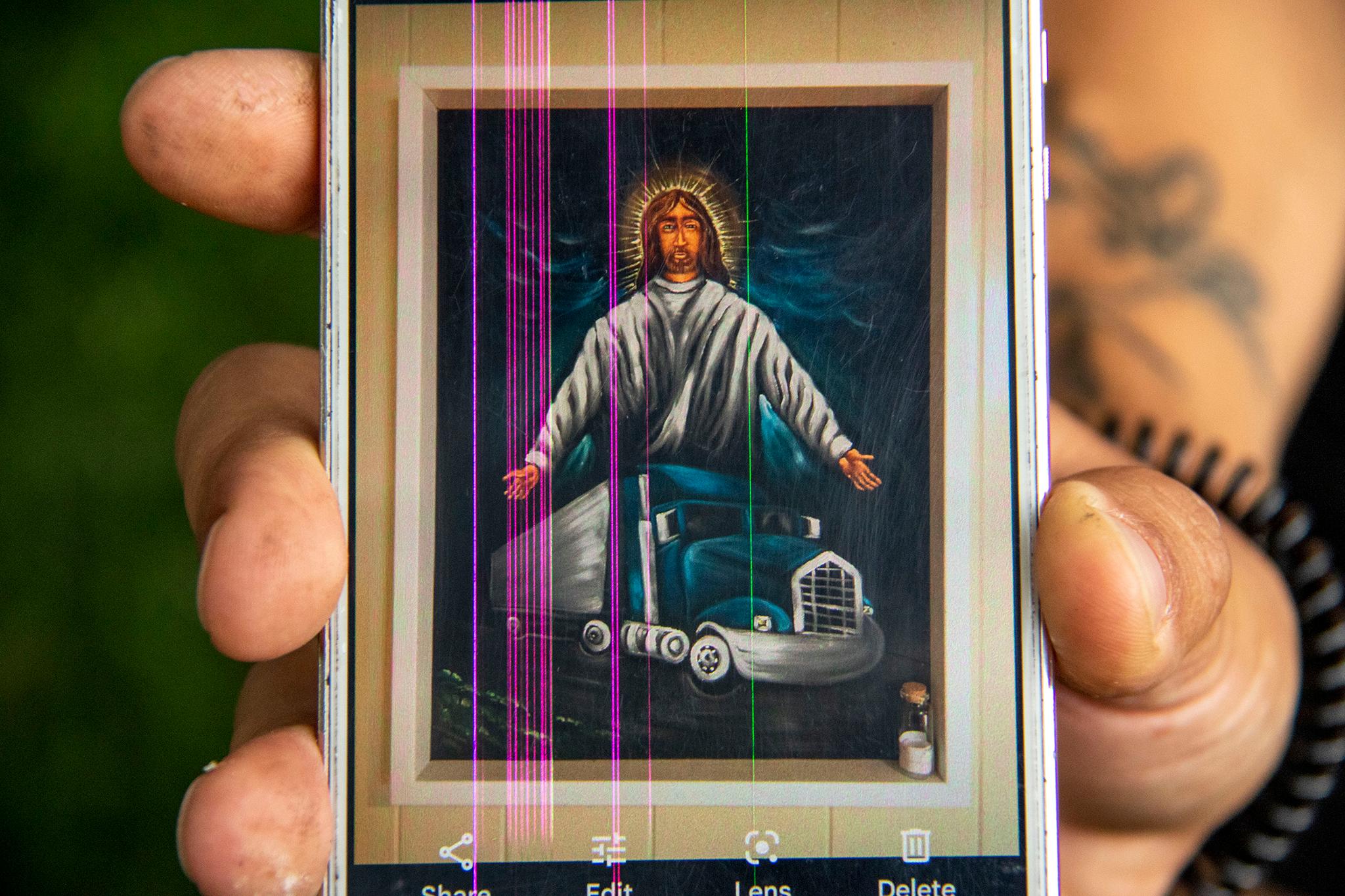

Biker Matt Sanchez remembered going to the now-shuttered Velveteria Epicenter of Art Fighting Cultural Deprivation, a velvet-art museum in Los Angeles. He was enthralled by a painting of Jesus standing above a semi-truck. When he returned to Denver, he told anybody who would listen about the museum and the painting. Most people shrugged him off. Javin, characteristically, was eager to hear about it.

A year later, Javin invited Sanchez to a party. An introvert, he said no. Javin pressed him to come, telling him he could pick up his birthday present. Sanchez's birthday was months away, so the whole thing seemed ridiculous, but eventually, he broke.

When he arrived, Javin eagerly took him to his massive present. Sanchez tore it open and saw Jesus, arms stretched out, standing over a truck. The painting, similar to the one he saw at the Velveteria, was enclosed in a frame built by a mutual friend who worked as a carpenter.

Javin had called the museum and begged the curator to sell the painting to him. The curator said no, explaining that the request was kind of like asking the Louvre to hand over the "Mona Lisa."

So Javin got the name of the artist, who was living in Juarez, Mexico. He hadn't been painting for decades, but Javin persuaded him to create a similar work -- only in this one, the semi would include a shadowy figure.

"And he's like, 'See this like shadowy figure in this semi truck?'" Sanchez recalled. "And I'm like, 'yeah.' And he's like, "That's you, man.'"

Sanchez described Javin's group of friends as "the island of misfit service-industry workers."

One of those friends, Daniel Greene, described Javin as "one of the best people I've ever met in my life. His work ethic would blow your mind. This guy worked from noon to midnight almost seven days a week on his bike."

He would save money to travel to Europe during the summer and pay for his friends to come along.

"If he had anything, it was everyone's," Greene said. "He had that kind of spirit."

Javin's former boss at Jimmy John's, Max Duarte, remembered him for his work ethic.

"Him in the snow -- he was like a f***ing tractor in the snow," Duarte said. "Three feet of snow, he's still running around town, delivering, just as fast as if it's dry outside, not giving a f*** about what's in his bag, just lovin' riding his bike in the city, swerving through traffic, making money -- just that, day in and day out."

In 2020, for Duarte's birthday, Javin surprised him with tickets to a show. COVID shutdowns canceled those plans. So instead, Javin bought Duarte a Surly bike -- what has become his favorite out of the six he rides.

"I get to keep a piece of him," Duarte said, pointing at the bike. "It's not going bad any time soon."

Alvin "Leo" Abeyta, who was friends with Javin in elementary school and then again at West High School, remembered him playing in a death metal band that never picked a name. After school, the two lost touch for years.

Around 2016, Abeyta reconnected with Javin after the Finnish metal band Nightwish played a Denver gig. The band's drummer invited them to a Los Angeles show.

They dropped everything, called into work, and drove 17 hours to the coast. Javin bought them backstage passes. After that, they continued to travel with the band.

"We did a little mini tour with them," said Abeyta.

Jordan Philippi first met Javin -- who went by Scott back then -- when he was a freshman at West High School.

"I was a punk," Philippi said. "I was a skateboarder. I felt kind of out of place walking through the hallways of West. It was lunchtime, and I was walking through the courtyard with the skateboard. He was the first person that came up to me. He also had a skateboard. He said, 'Yo playa, can you ride that thing?'"

The two played H.O.R.S.E. on their skateboards. One would ollie off the curb; the other would follow. They would each take a turn kickflipping. Nothing too fancy. Ultimately, Javin won, and the two became close friends.

It took years for Javin to share his real name with friends, Philippi said.

Growing up, Javin's family pronounced his name Jay-vin. After he vacationed to Norway, where the elite Black metal scene took him in, he started pronouncing his name Ya-vin, Philippi recalled.

Javin occasionally joked with his Patagonia co-workers that he'd start going by Gavin, they said.

Years after high school, Philippi managed the downtown Jimmy Johns where Javin worked. For three months, the two didn't recognize each other. At first, Javin couldn't stand his new boss -- and relished telling him that, especially after they began to grow close.

One night at a party, Javin told Philippi he looked like someone he went to school with. They realized they had both been at West at the same time.

"Did you go by Scott?" Philippi asked.

"You're f***ing Jordan," Javin replied.

After that, they were tight again.

Denver musician Megan Crooks remembered Javin for protecting women, including her.

She was working with him at Jimmy Johns. One day, when Javin was delivering sandwiches, a manager groped her. She wasn't comfortable telling her supervisor, so she called Javin and he offered to mediate the conversation. When Crooks and Javin spoke to the supervisor, he defended the manager.

"Dude, she's not f***ing making this s*** up," Javin said.

"He just really stood up for me," Crooks said. "But then he also gave me some space to tell my own story."

She witnessed him intervene at drunken parties.

"If there's a situation where somebody's getting out of hand, or if a woman feels uncomfortable, he was always f***ing there, ready to protect and make sure that people were feeling safe," she said.

When her bike was stolen, he made a significant donation to her GoFundMe. When she needed help with rent or groceries, he offered to chip in. And once, when they were practicing riding down a hill without holding onto their handlebars, she tipped over and he caught her bike by the saddle and attempted to ride her to safety. Instead, they crashed.

Javin never learned to drive, said Garcia, but he was passionate about bike safety.

One of the companies he worked for sent him to California to teach workshops in bike law and riding.

He carried stickers that said "Stop parking in the damned bike lane," recalled Sanchez. He would ride around town slapping them onto cars that violated that creed.

His loved ones hope drivers -- and the city -- do more to keep other bikers alive.

"Colorado is huge on bikes," Garcia said. "People: Be careful and look both ways. I encourage people to learn that bike law, because not very many people even know it."

This was the second time in less than two years that Javin's former coworker and friend Joshua Miller was in Cheesman Park mourning the loss of a fellow courier.

Miller wished drivers were required to learn the latest cycling laws and respected cyclists.

Said Miller: "It's just unfortunate that people are the way that they are in cars."