Who should run taxpayer-funded city parks and cultural centers?

In Denver, the answer has historically been the city. But in the case of Civic Center Park and the cultural center the McNichols Civic Center Building, that could change in Michael Hancock's last few months as mayor.

In recent weeks, Denver Arts and Venues and Parks and Recreation proposed the idea of shifting the programmatic management of Civic Center Park to the nonprofit Civic Center Conservancy.

Hancock's considering the idea.

"Denver's Civic Center is our pride and joy," wrote Deputy Communications Director Gabrielle Bryant. "We've worked hard over the past year to make it a safe and welcoming space for everyone. Mayor Hancock is pleased that city agencies are exploring, along with the Civic Center Conservancy, other models and new ways to enhance, activate and better manage our crown jewel."

If passed, the shift would create a new precedent regarding how private institutions might manage some public parks in Denver -- though city agencies insist the park would still be public.

This one-off arrangement would be the sort of "public-private partnership" the Hancock administration has embraced.

Ginger White, head of Arts and Venues, likened the proposed Civic Center and McNichols arrangement with Civic Center Conservancy to the one at the Colorado Convention Center, where the city owns the space but ASM Global manages it.

"This is not about privatizing the park. I want to be very, very clear on that -- very clear," said Mark Bernstein, chief of staff for Parks and Rec. "It is critically important that Civic Center remains Denver's civic space."

The history of Civic Center Park and the McNichols Building is a story of Denver's hopes and struggles.

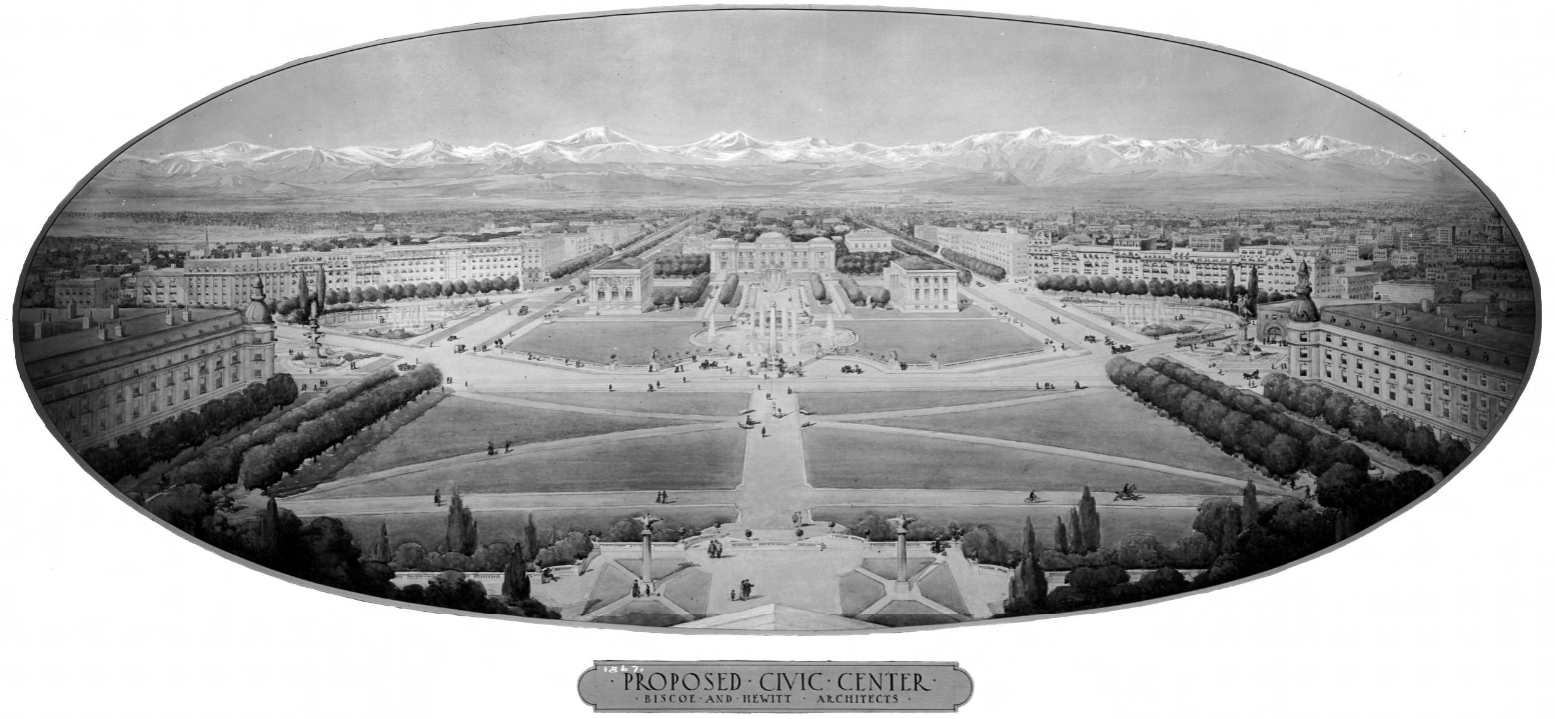

Mayor Robert Speer dreamed up Civic Center Park as part of his City Beautiful movement that brought neoclassical architecture to the city's parks and public spaces. Construction on the park began a year before he died in 1918.

His take on the park: "I believe it will do more than anything else to advertise Denver -- attract the tourist, health and home seekers; stimulate civic pride and encourage prosperity to abide with us."

The McNichols Building, originally a Carnegie Library, was built in 1909 and served as the city's Central Library until the current building was constructed in 1956. After that, it became a tired municipal building for decades.

In 2005, the city set out to reimagine Civic Center Park, and in that planning process decided to renovate the McNichols Building and turn it into a hub for culture. The remodeled building opened in 2016, under the management of the city's arts agency.

Civic Center Park has a long history of people being dissatisfied about how it's being used, who is there, and whether their activities are worthy of the site. Regular, mostly commercial activations like Civic Center Eats, which have become more popular in recent years, have been one way to gently instruct people on how to use the park: visit on breaks from work, dine from food trucks, peruse public art, and move on.

More events, particularly ticketed ones, limit who uses the park and when. Loud concerts or busy events mean fewer people idling in the grass.

The public has weighed in on the park's future again through the Civic Center Next 100 planning process, led, in part, by the Civic Center Conservancy.

Here's how the Conservancy framed the plan: "For Denver, our crown jewel is Civic Center Park. Located at the heart of the city and surrounded by many of our key civic and cultural institutions, it has served as Denver's most significant gathering spot for cultural events, festivals, civic protests, rallies and our country's most celebrated holidays. And while it has served us well for the past 100 years, it is the responsibility of the Civic Center Conservancy to shepherd the park's evolution and transformation to ensure it meets the needs of Denver residents for the Next 100."

The park lives up to its name: It's a center of civic activity.

Civic Center boasts a massive public art collection and often hosts temporary exhibitions as well as major cultural events, from Denver Pride, Cinco de Mayo, and the Mile High 420 Festival.

When people protest in Denver, they tend to converge in Civic Center -- on the steps of the Capitol, in the park itself, and even at the City and County Building. The park has seen encampments associated with the anti-capitalist Occupy Movement, along with protests for abolishing Columbus Day, the Women's March, the movement for Black lives, stricter immigration control and more immigrant rights.

But its history isn't just civic and cultural engagement.

For years, Civic Center has been an off-and-on hub for drug dealing and drug use. At times, the park has turned into a massive encampment.

The space has also seen some violent crime and even higher levels of worry about violent crime. In September 2021, an encampment was swept and the park was fenced off in the name of public health and safety -- a move that left many questioning just who the park was and wasn't for.

More recently, Civic Center has been coming back to life -- and the Conservancy hopes to lead that renewal into the future.

Since the start of the pandemic, "this is kind of really the first summer where, you know, things have been 'normal' in the Civic Center ecosystem," said the Conservancy's Executive Director Eric Lazzari.

This season saw the return of popular events like Civic Center Eats and the annual Independence Day festivities.

So who runs Civic Center now?

For years, the Conservancy has been a big force in programming in the park, but it has been one of four groups, including Parks and Rec, which runs the park itself, Arts and Venues, which runs the McNichols Building, and the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, which runs the shut-down section of Bannock Street between the park and the City and County Building. That strip was turned into a car-free, public plaza in 2020.

The Conservancy, if granted greater managerial oversight, hopes to bring even more events -- both free and ticketed -- to the park, the McNichols Building and even Bannock Street.

"One of the things that's appealing to all the partners involved here is we can, as the Conservancy, look at all of the assets in the park, whether that's McNichols, Bannock, the Greek Theatre, the Great Lawn, the Broadway Terrace, all the different parts of what the public knows as Civic Center -- and have a unified plan and a unified vision on how we maximize use out of all of them," Lazzari said.

Civic Center Conservancy has a legacy of its own.

When the city began its master planning process for the park under now-Senator, then-Mayor John Hickenlooper's administration, planners envisioned a nonprofit that could help the city with running and preserving the park.

The nonprofit was founded around that same time, and its role in the park was included in the planning process back then, according to Bernstein of Denver Parks and Rec.

Over the years, the relationship between the Conservancy and the city has been active. The nonprofit has pushed beautification projects and live events to ensure the park is a place for the entire community, sometimes after massive sweeps of encampments from the Department of Public Health and Environment and crackdowns on drug users by the Denver Police Department.

Lazzari, as a leader, has tried to address the issues the park faces with greater collaborations and is unwavering in believing that the park is for everyone -- not just people who happen to have homes.

Both the Conservancy and Parks and Recreation have worked with homeless service providers to connect unhoused people with resources.

"Civic Center is a place for everyone, every day, and that is not lip service," Lazzari said. "That is one of the core things that we believe. We also believe that anybody that is coming and using the park, you know, we all have a social contract with each other and how we treat one another and how we treat the space and things like that. It's challenging at times and has less to do with housing status and how we are working with each other and managing it."

More recently, the Conservancy launched a program, Civic Center Works, to hire unhoused people to help maintain the park.

The nonprofit refers to its staff as a "small but mighty team," with two full-time and one part-time employees. The board of directors includes politically connected heavyweights from developers like East West Partners, the hotelier Sage Hospitality which runs Union Station, the lobbyist group CRL Associates, banks, city agencies, and the law and lobbying firm Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck.

Here's what the Conservancy would take on if the plan is approved.

At the park, the nonprofit would curate and manage daily activations and programs; provide a unified approach for managing, booking and permitting in the park; and manage assemblies, special events and private events, according to a Powerpoint presented to the mayor's office.

As for the McNichols Building, the Conservancy would take over booking, strategy and implementation, building management and operations, and capital planning and investments.

Arts and Venues would likely focus its own programming elsewhere in the city -- including at the May Bonfils Theater at the redeveloped Loretto Heights, where the agency is also in talks about acquiring the library for public performances, White said.

The city named three main reasons the transfer of power makes sense.

The shift in managing programming would create a more singular vision for Civic Center, set the nonprofit up for greater financial success as the park's nonprofit steward, and avoid conflicts between events and other uses of the various parts of the space.

In the current arrangement, events at different parts of Civic Center -- namely, the park and the McNichols Building -- compete against each other. White described how noise from outdoor events can bleed into the McNichols Building and how scheduling to avoid that between multiple agencies can be difficult.

"There's a lot of cooks in the kitchen when it comes to Civic Center Park," White said. "We think that this creates a better or more holistic vision for the park and then the opportunity for the conservancy not only to create that vision but to execute on that vision in a more singular and holistic way."

The shift would also increase the number of events at Civic Center Park, which would bring in more money to reinvest back into the park.

The arrangement would look a lot like those in other cities where conservancies run the parks: New York City's Central Park, Piedmont Park in Atlanta and Klyde Warren Park in Dallas.

The city also noted a few things that might not work so well if Civic Center Conservancy takes over.

The city questions whether the Civic Center Conservancy is big enough or experienced enough to take on a massive increase in responsibilities.

Lazzari, too, acknowledged the organization is not currently staffed at the level it would need to be to take over the park.

"We know we have to scale up to fulfill this," Lazzari said. "We're excited to scale up, because we think there's a lot of great opportunities there."

The nonprofit is having conversations with funders about the potential growth.

District 10 Councilmember Chris Hinds is interested in the proposal, but does have one big reservation.

"I want to make sure that if we do that, we place our trust in a durable organization," he said.

The Conservancy, which is thus far the primary organization to be floated because of its longstanding ties to the park and the city, is thinly staffed. There wasn't a competitive process for multiple organizations to have a chance to manage programming at the park.

"While I think that the current executive director is a great fellow, he's running all the show," Hinds said. "And so if he wins the lottery, that could be concerning, if that means that maybe no one would be shepherding a very important park and assembly place in our city.

"So as long as we can work out some of the details to make sure that it is a durable organization, I think it's a great idea," he concluded.

So what's next?

This transfer of managerial power to the nonprofit would take place gradually.

The mayor will need to sign off on the plan. City Council will need to approve associated funding. Parks and Rec, Arts and Venues and the Conservancy would then team up to pay for a Civic Center Administrator to bridge the gaps between the organizations during the shift in management.

At first, Parks and Rec and Arts and Venues would continue to be responsible for daily operations, management and rule enforcement; the Conservancy would receive any earnings from events and permitting to put back into the park; and Arts and Venues would help subsidize the Conservancy's costs of running Civic Center.

Said Bernstein: "Because of how our partnership with the Civic Center Conservancy has grown and evolved over the last 16 years or so, we believe we're at a really great place now where it's a good time for us to start thinking about how we can really serve, expand and grow that partnership more."