When Musa Bailey cooks dinner for his son Glenn, he turns on the jazz station KUVO. But the public radio station founded in 1985 just doesn't sound the same anymore, Bailey and other longtime listeners lament.

For some, that's because the music has veered toward what they call "smooth jazz." For others, the departure of four favored hosts has left them mourning and wondering if the station will survive. Some believe the merger with Rocky Mountain PBS under the Rocky Mountain Public Media umbrella has corporatized what was once a mom-and-pop shop driven by a pure love of jazz and an authentic connection to the Five Points community.

The station itself is wrangling with many big changes.

In 2020, the station moved from the cozy but dusty Five Points Media Center on Welton Street to the state-of-the-art Buell Media Center closer to downtown. Then came staff transitions with a push to expand audiences that sometimes chafes hosts' and listeners' cultural and aesthetic priorities. KUVO's been trying to grow its audience with new programming while pleasing longtime donors and volunteers who are allergic to the new audience-friendly direction.

The biggest shift: The impending retirement of veteran General Manager Carlos Lando, and the arrival of new Program Manager Max Ramirez, the third program manager in the station's history. He's a self-professed "radio nerd." At a meeting where KUVO fans were blasting changes he'd enacted, he joked that he's so young "I might as well be wearing diapers" and boasted that at the last radio station he worked at, a Kenny G photo was a Halloween decoration.

Ramirez said he understands that there is a lot of dissatisfaction, at a public meeting Tuesday night.

"I take that. I internalize it. I try not to take it personally. But I do personally care," Ramirez said. "It does affect me. And I want to make sure that going down the road, we do communicate better. I accept that. And that's on me. We should be more transparent, even more so than we are."

Many of KUVO's changes aren't talked about on air -- but the effects of them are loud to listeners, who wonder what's going on behind the scenes.

For Bailey, KUVO is a Denver institution that dates back to his childhood, when his dad would pick him up from school and blast jazz standards all the way home.

In the decades since, Bailey became one of the city's most prominent hip-hop DJs. He toured with Saul Williams and spun samples with members of the Wu-Tang Clan at Red Rocks. He opened and closed the club Cold Crush, and in recent years, he's worked on a stop-motion animation with his son, meticulously moving action figures one frame at a time, as jazz played in the background.

As a DJ, he researched music to sample while listening to KUVO's shows, a mix of jazz and blues standards, contemporary fare, Latin jazz and other music from around the world. The station was a place to discover great, yet unfamiliar tracks.

Bailey's favorite KUVO host, Rodney Franks, hosted the 4 to 8 p.m. slot since 1995, spinning a mix of contemporary and classic jazz.

"Rodney is the voice of that station to me," Bailey said. "He's the person I look forward to hearing talk, his humor and his knowledge of the music. He's spent his life studying that form."

Earlier this year, Franks' voice disappeared from the air. So did another favorite of Bailey's: Susan Gatschet, who one KUVO listener recently described at a meeting with the station as "my spirit animal," adding "I love her." Jazz musicians remember her for attending nearly all of their shows and being an ambassador between KUVO and the community.

Both Franks and Gatschet were fired, and they were not alone in having rough departures, Franks said.

Longtime host Janine Santana said she was also pushed out, with her hours cut so short she was no longer eligible for benefits and her schedule altered to conflict with her dying son's medical appointments.

Matthew Goldwasser, a volunteer who ran a one-hour show, also said he was iced out after raising concerns with Rocky Mountain Public Media leaders.

Gatschet was not available for comment.

The loss of those four hosts left listeners and staff wondering why and where their favorite personalities -- on-air talent some considered friends and others family -- had disappeared.

Amanda Mountain, CEO of Rocky Mountain Public Media, declined to comment on the specific reasons staff and volunteer hosts left out of respect for their privacy.

Lando, KUVO's general manager who has been in the process of retiring for several years, said the changes stemmed from conversations with Ramirez back in February.

"Me and my program director, Max Ramirez, who I hired at that time, we were reassessing our programming and how to appeal to younger audiences, and just really looking at the face of jazz, as it is today, how the music was evolving, where the influences were coming from," Lando said. "And we realized that we really needed to kind of expand our horizons."

From the beginning, KUVO's gone through programmatic shifts to connect with the wider community. When Flo Hernandez Ramos and other Latinas set out to found a Spanish-language public radio station back in the '80s, they spoke with the broader community and learned that what people really wanted was an English-language jazz station.

So they pivoted and delivered. Shifting to meet the community where it's at is in the organization's DNA. And over the years, as jazz has evolved, so has KUVO's programming.

But with change comes disagreements, and when staff resisted new directions, they ended up leaving -- some by their own choice and others by the station's.

"There's going to be people who are completely on board," Lando said. "There's gonna be others who aren't quite on board."

Franks described the programming direction as a "dumpster fire" and said both Ramirez and Lando were "out of touch."

There were new restrictions on playing songs longer than six and then eight minutes on air during daytime slots -- a decision Lando and Ramirez made to appeal to the wider public, who might tune out during long jazz tracks.

"It's just going to eliminate any live music from Keith Jarrett, most of John Coltrane, most of Charles Mingus, all of these classic tracks from Blue Note," Goldwasser said. "It's just going to evacuate the canon."

Instead, Franks said, the station was taking a "more elevator-music approach" to programming.

"We're over 90% listener supported," Santana said. "Listeners had no idea this was going on. They did notice that there were changes in the format and that a lot of it was kind of like, 'Why are we playing Dave Koz? Why are we playing Kenny G? Oh my God, what's happening over there?'"

As Franks tells it, what the station is playing isn't as contemporary as Ramirez and Lando think it is, and they're skipping too many great new artists.

"The musical choices are still back in the '80s or '90s," Franks said. "When he made the statement, 'I want to bring new people in. I want to change the sound of the station to bring more people in,' you don't do that with smooth jazz... Smooth jazz is the demographic of 50 to dead. They're trying to reach 25 to 34. Uh...I don't think so."

As for the argument that smooth jazz would appeal to younger audiences, Bailey, who knows how to get crowds moving better than most, recoiled.

"They're not listening to f****** smooth jazz. They have a better chance with Miles Davis and John Coltrane than they do with Kenny G or trying to shift into sort of adult contemporary station," Bailey said. "It feels like the powers that be are giving up on the traditional jazz format. And that saddens me."

"Smooth jazz" is a dismissive term for contemporary music, argued several current KUVO hosts at a community meeting, and the station is not abandoning jazz.

"I have an issue with people hating on smooth jazz," said host Mike Wulfsohn. "I'm brought up on straight-ahead jazz, blues, small group, big bands. I love it all. Duke Ellington said, 'There are two kinds of music: good and the other kind.' We make sure we don't play the other kind."

Mountain said criticizing newer forms of jazz is part of the history. And the changes in programming are designed to open up the artform to broader audiences.

"I love traditional jazz," she said. "That's how I came to know the music. But I also know that in order to expand the cultural relevance of the station, we can't be so exclusive, like we need to make room for the lexicon of jazz as a format that has evolved over time as a reflection of American history, quite frankly. And we don't want to be an organization that shuts its doors to people who aren't coming in through that pathway."

The firings and forced resignations, as the hosts who left describe it, were ill-timed and presented as amiable departures.

In May, a PR firm representing Rocky Mountain Public Media, KUVO's parent company, sent out a cheery press release about the arrival of Ramirez, the new programming director. He had moved to Denver from Indianapolis after working as an assistant program director at the University of Indianapolis's radio station.

"Ramirez and Lando, together with KUVO JAZZ staff, volunteers and management, are re-imagining the station's footprint in the jazz community while ushering in a new era and lineup for the station's new and long-time listeners alike," the release stated.

Missing from the lineup was Franks, who said he had been fired in April, days after returning to the office from time off mourning his father's death.

"The reasons given were my numbers had not been up to par," said Franks, who had always been evaluated based on fundraising metrics, not Nielsen ratings. "From the 30 years I'd been working at KUVO, the numbers had not been an object until a new programming director came in."

The note to the public about Frank's departure was friendly: "As we work to put these changes in place, we want to take a moment to thank Rodney Franks, who has been our friend and colleague for over 10 years... While he is no longer with the station, we are grateful for his contributions and we know his listeners will join us in wishing him well."

Franks, still mourning his father, was surprised to read their fond farewell. He was too busy settling his father's estate to fight for the job he loved.

"Getting fired from KUVO was really a blow to me," he said.

Several hosts described Ramirez as "a hatchet man," hired to clean house before Lando retired, and Franks was just the first person he cut or pushed out.

After him, longtime host Susan Gatschet was also fired, days after returning from grieving her own father's death. Santana, too, had been dealing with multiple family medical emergencies and her parent's death when she was pushed out, she said.

"There's a pattern in the way Carlos does things," Franks said. "He waits till a person is at their lowest, and then he fires them."

Ramirez did not reply to Denverite's requests for comment on this story.

When asked about the timing of the firings, Lando became emotional, citing recent deaths in his own family and how Rocky Mountain Public Media supports staff with generous paid time off.

"I know the three people you're referring to," Lando said. "We have been supportive. We care. This is family, and it matters to us. At the same time, we continue to work with people coming to work and doing what we expect of them. The bottom line here for us is that yes, we support you and so forth, and we're sorry this is happening at the same time. I think we're really sensitive to that."

Those who lost their jobs and benefits disagree. Franks said he would not return if Lando and Ramirez were still there.

Many in the community wish he would.

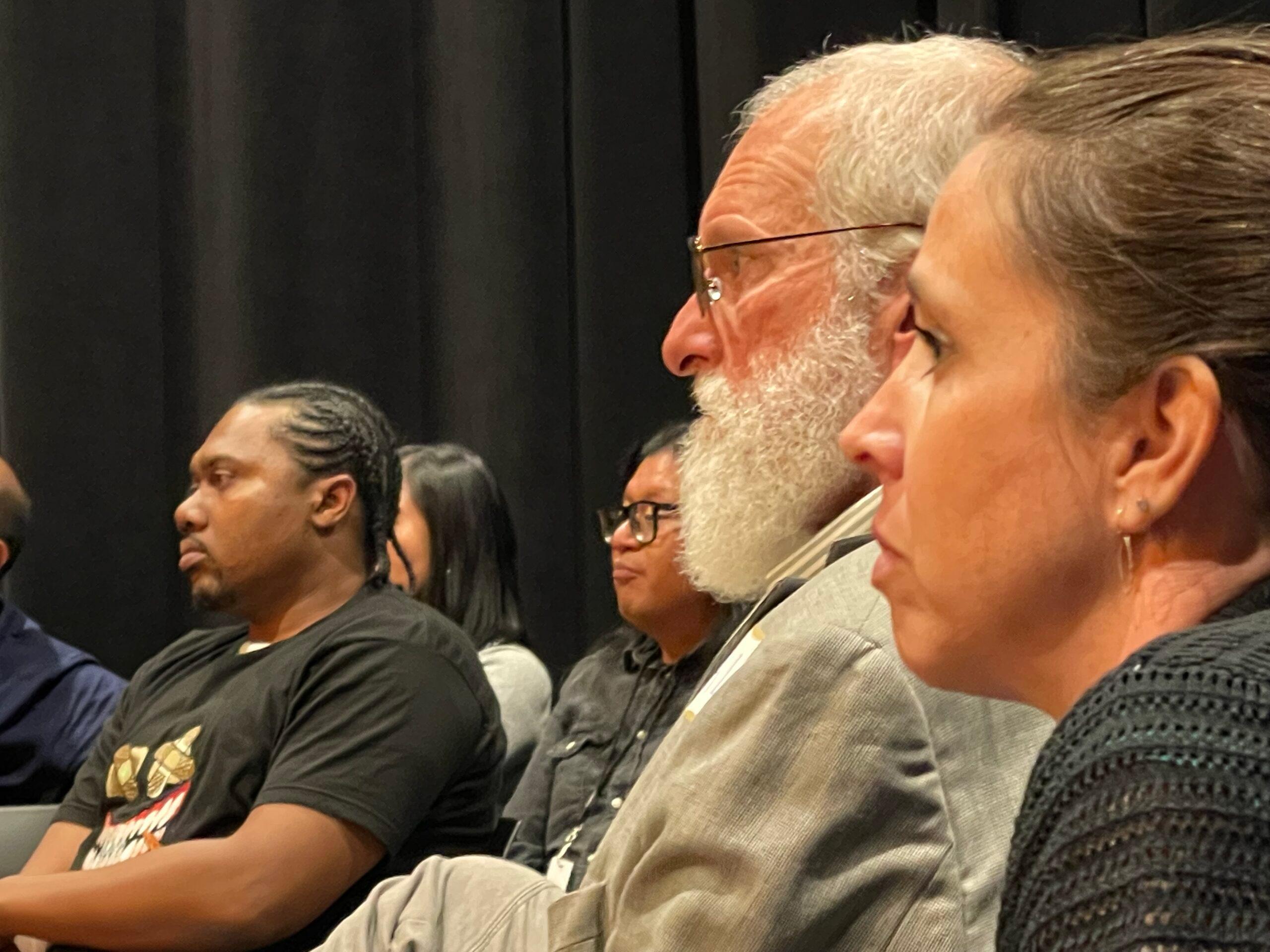

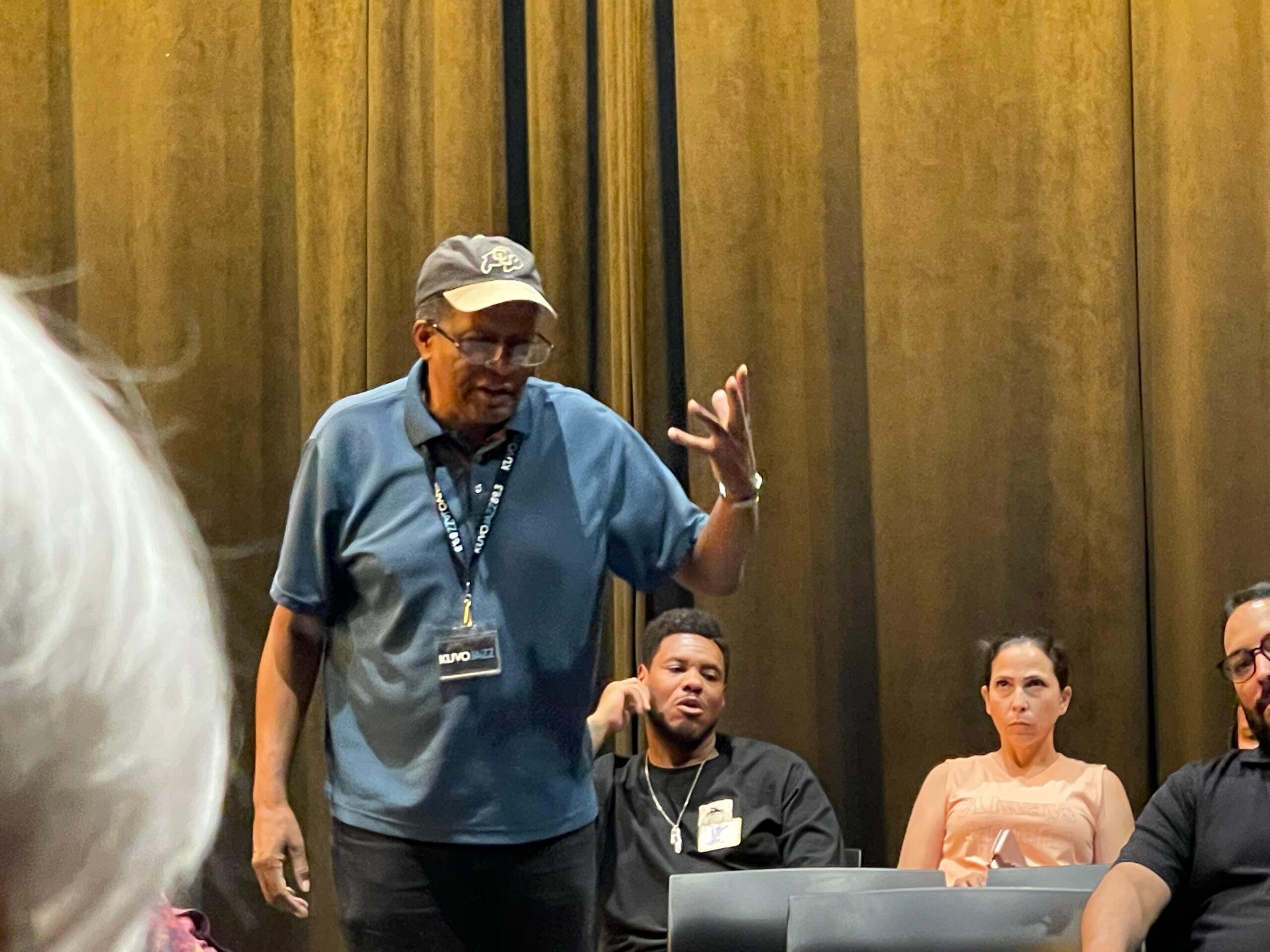

In response to listeners' concerns and social media outcry about the changes at the station, KUVO is hosting a series of listening meetings, facilitated by an in-house conflict mediator.

On Tuesday night, many of the old-time hosts and personalities -- Adam Morgan, Andy O', Music Director Arturo Gómez, Bella Scratch, Gabriel, Pocho Joe -- and volunteers, donors, and Rocky Mountain Public Media brass sat together in a square, in a large studio at the tony Buell Public Media Center.

The conversation was funereal, both an exercise of love and deep disappointment for volunteers and donors.

Jazz pianist Annie Booth said listening to KUVO as a kid inspired her successful career as a professional musician. The hosts who were fired would show up in the front row of her gigs, every time she played. They showed her unflinching support.

"To have people who care so deeply about the community let go, it's shocking to see it," Booth said. "And it makes us scared that that tie is being broken."

Paul Romaine, founder of the Colorado Conservatory for the Jazz Arts, talked about how the city's jazz musicians and fans love each other like a family.

"This station, historically, has been a huge part of that glue that keeps us all together," he said. "They've done an amazing job of that. It feels like, you know, there's this move that just sucked the soul right out of this station. And it's palpable. It's palpable in the music community. I think it is palpable in the listening community.

"It's deeper than just numbers and logistics and demographics and predictably and all of that kind of stuff," Romaine said. "It's almost like we lost a whole part of our family."

Hosts Mike Wulfsohn and Adam Morgan walked in as he said that. Morgan wondered if somebody had actually died and shouted: "Why is everybody so grim in here? Am I in the wrong spot? We've got a happy station here. Sound like it."

Both Lando and Ramirez offered to meet with concerned listeners and donors one-on-one.

The next meeting will take place Tuesday, September 27, at 6 p.m. online. The platform is still being determined.

For Bailey, the shifts at KUVO mirror other cultural trends in Denver.

"This town really gets me down sometimes," Bailey said. "One of the last cool things we had going here -- now that's even up for grabs or up for debate."

Denver, as he sees it, is struggling with its identity and is too quick to trash older parts of the city's culture -- and the changes at KUVO are part of that trend, he said.

"It just makes sense in the dystopian Colorado that I'm living in right now," Bailey said. Yet he's happy to see people fighting for KUVO's legacy. "I'm not the only one who's pissed off about this," he said. "So there's hope. I'll leave the silver lining there. People aren't happy about this. So that means that there's still people here that are fighting for a kind of Denver that I still find endearing."

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated Ramirez worked at the University of Indiana radio station. He came from the University of Indianapolis radio station.