A handful of people hung outside a Denver rec center on Friday morning, chatting, laughing and sipping coffee. They said they'd been sleeping on cots inside that city-owned building, that they were treated with kindness, that they were comfortable and grateful for the support. They also said they weren't supposed to talk about themselves to anyone, so while some spoke, none offered their name. Those who did speak to us told us they'd come from El Paso, Texas.

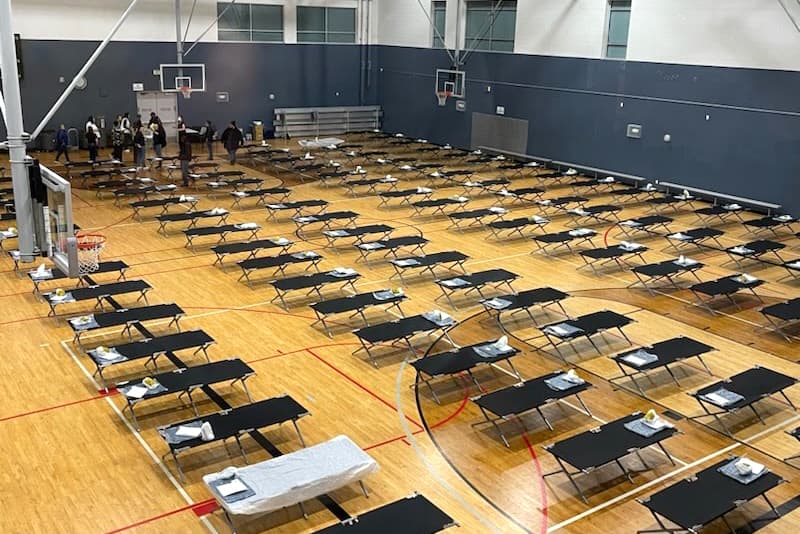

These were a few of at least 100 migrants from Central and South America, including Venezuela, who Denver offered shelter this week, after a large group showed up unannounced at the Denver Rescue Mission on Monday night. One person had already landed a job. Another just arrived Thursday night.

They're part of a much larger movement of people from all around the world to the U.S. southern border and, sometimes, into the heart of the country. Generally, people who recently crossed the border and joined the last leg of that trip into American cities have already been held by border patrol, released and allowed to remain in the country as they pursue asylum or other claims to stay for good. Others, who get denied entry arbitrarily or have criminal records, are sent back to Mexico.

For days, media pressed city officials and nonprofit workers for details. Was this a political dig from an adversarial governor? How could so many people show up at once? Who coordinated this?

The reality is probably not so scandalous. Border cities like El Paso have long sought to care for people released into their communities by border patrol, and there are often not enough resources to help everyone. Denver may have just been a better place for people to land.

El Paso, in particular, has been overwhelmed by humanitarian need.

Ruben Garcia is the executive director of Annunciation House, a nonprofit in El Paso that's served people crossing into the country for almost 45 years. As migrants - or "refugees," he prefers - stream into the city, his organization offers people a place to sleep, warm meals and individualized conversations to help families and individuals get to wherever they're heading. Many people who make it into the U.S. and plan to apply for asylum have friends or family elsewhere.

The "capacity" that cities and organizations have to offer these services is a hard thing to pin down, he told us. It's influenced by an ever-changing set of political priorities and policies, and logistical realities on the ground. On Thursday, he told us, Annunciation House shepherded 1,100 people to churches and other shelter spaces nearby in Texas and as far as Omaha, Nebraska. Last Monday, they were able to help 1,300 people. Weekends are trickier, he said, since the churches he relies on have Sunday services. He clarified, however, that he didn't know about the large group that arrived Monday.

It's a lot of people to help every day, but Annunciation House can't serve everyone released into El Paso. U.S. Customs and Border Protection is only allowed to hold people for 72 hours, and thousands have recently just been dropped on city streets.

To help people avoid navigating the country on their own, Garcia said his organization has been working to grow a network of faith groups and nonprofits who will offer similar hospitality in other states. They've already been working with nonprofits in Denver, who have agreed to take in 50 people a month as they try to ramp up their own capacity. Still, Garcia said El Paso needs more partners.

"It's not just Denver. We are slowly trying to build a network of faith communities in different parts of the United States that are willing to receive a bus of refugees, and to receive them and offer them the exact same hospitality that is offered to them in the church facilities here," he said.

Laura Cruz Acosta, a spokesperson with El Paso's municipal government, told us the city has also worked to address the influx of people. They opened a "Migrant Welcome Center" between Sept. 7 and Oct. 20 that helped new arrivals move on to other parts of the country.

"We received both sponsored and unsponsored migrants. The sponsored migrants have the funding to pay for their transportation to their final destination and so we assisted in travel coordination," she wrote us. "The migrants who did not have a sponsor or means to pay for their travel, the City served as their sponsor and provided charter buses to where they wished to go. NYC and Chicago were the two cities most commonly requested by the unsponsored migrants."

Cruz Acosta added they would not re-open the processing center unless the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) "can provide upfront funding." The city is still waiting to be reimbursed for money they spent the first time around.

Laura Gallegos, a spokesperson with El Paso County, told us the county has been running a similar processing center that serves 500 people, seven days a week.

Immigration is a national issue, and a lot of people are saying the impacts of federal policy don't belong just to El Paso or Texas.

One reason Annunciation House must grow its network of support, Garcia said, is to spread out that burden. But it's not the only reason.

"We want to send buses to faith communities in the interior for the reason of helping to spread out the responsibility," he said. "Secondly, to give faith communities the opportunity to live out their faith. Third, to help communities listen to the stories of people, to better understand what is happening. Why is this happening? What does it look like?"

The idea that border states should not be alone in receiving people entering the U.S. is also part of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott's explanation as to why he sent busloads of people to cities like New York and Philadelphia, though his language is a stark contrast to Garcia's. Abbott's letter to President Joe Biden was swaddled in tropes, calling migration an "invasion by the Mexican drug cartels" and blaming migrants for the country's fentanyl crisis, though most drug busts happen at regular legal points of entry.

Abbott's office did not respond to our request for comments.

Fernando Garcia is the executive director and founder of the Border Network for Human Rights, an advocacy group that's been pushing for immigration reform since 1998. He doesn't think about sharing responsibility in terms of geography; instead, he said the onus is on the federal government.

"For the last 30 years, the only infrastructure that's been built at the border is an infrastructure to detain and deport and reject migrants and refugees. The billions of dollars that's been invested has been for border walls, larger border patrol, more detention centers. No welcome infrastructure. The fact there's no resources to process migrants is because we have not invested in that," he told us. "This has been a major failure of our national policy across the border. It's caused by both parties, Republicans and Democrats."

Gallegos, with El Paso County, told us something similar:

"The County understands that this irregular migration will continue until Congress takes concrete and meaningful steps to reform our outdated immigration laws. In the meantime, border communities with limited annual budgets continue to shoulder the responsibility."

While the question, "Who sent them?" might be moot, "What happens next?" is still super relevant.

Fernando Garcia has been working on the border for decades, and said the recent influx of people into places like El Paso is nothing new and probably won't be a forever thing.

"What we're seeing is an uptick in immigrant crossings, and I think we're going to see it for the next few weeks and months, but I don't think it's going to stay there permanently," he said. "Numbers, they go up and go down. The problem is the way we manage them at the border."

Still, most everyone watching the border is bracing for another wave of people if Title 42, a Trump-era policy that used COVID-19 as a reason to turn asylum-seekers away from the border, will be overturned. The Biden administration did try to overturn the policy, but also recently sought to block its cancelation. People are waiting in Mexico for the policy to end, so they can enter the U.S. and ask for asylum, and that fact was one reason Denver officials gave resources to local advocates to set up a more permanent version of the emergency shelter set up now at the unnamed rec center.

Those advocates are asking Gov. Polis to set up shelters across the state. His office told us they're "assessing how the state can be supportive" to help cities and nonprofits house "unsheltered people."

A spokesperson for Denver's Joint Information Center (JIC), which was activated along with the city's Emergency Operations Center last week, said they're still responding to the immediate situation.

"Right now, our efforts are being focused on relieving the strain on our local shelter system. Coordination and conversations will continue to happen to determine what we have to do to meet future needs," the unnamed spokesperson sent in an email.

On Saturday, the JIC announced it was sheltering 152 people at the rec center, while 48 had move to a space run by a local church. They're also asking residents for donations.

Ruben Garcia, with Annunciation House, said conversations about future support will continue to be necessary and important.

"This is why it then goes back to the question of, 'Who are we? Who are we? You know, who are we?' And we've all got to answer that question," he said. "I applaud the city of Denver for saying, 'Hey, we have to recognize that this isn't something that belongs just to El Paso, to Brownsville, to Nogales. It applies to us as well in the interior, and we need to take some steps.' So I applaud the city of Denver for taking that step."

May Ortega and Stephanie Rivera contributed to this report.